As an addictive refreshment beverage, coffee has always been synonymous with “spiritual boost.” Coffee shops, at the same time, are where inspiration meets innovation, and hold the superior position that sets the trend of the times.

Looking back on the coffee industry, from Paris in the late 19th century, Seattle in the late 1980s to Tokyo in the 1990s, we observed that the rise of a new coffee brand is always synchronized with the rise of a special group.

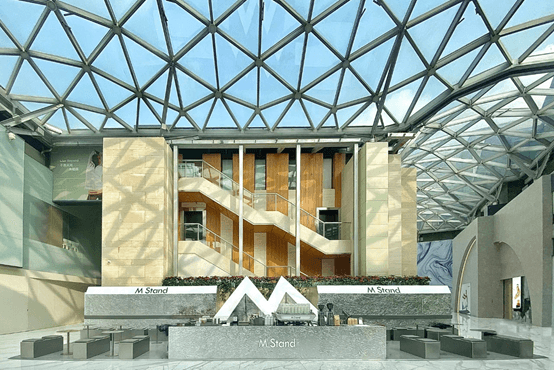

M Stand, GenBridge Capital’s recently invested portfolio, is one of the most representative new-generation chain coffee brands. The maturation of Chinese consumers leads to a greater focus on products’ social and cultural value, besides their use value. This demand, has, in turn, sparked the birth of new brands and new business formats, meeting the needs of new-generation consumers.

GenBridge Capital welcomes more entrepreneurs in the consumer sector to join us to share insights on innovative business formats themed around “New Demographic, New Demand”. Below, through the study of the development history of boutique coffee shops, we hope to share our understanding of the core logic of this sector and our prediction of future trends.

Parisian Arcades Street: A Catwalk for the Middle Class Frequented by Literati and Philosophers

The modern coffee shop industry emerged in the late 19th century in Paris. During this time, Paris experienced its golden age. The French Revolution has promoted freedom and equality, and the Industrial Revolution has driven economic development, transforming the entire city and country.

Amidst these colossal changes, a new social class emerged – the bourgeoisie. From a modern perspective, they were affluent citizens with cars and houses. Unlike the privileged nobility or rural farmers, the bourgeoisie enjoyed the dividends of the Industrial Revolution and colonial economic benefits, actively participating in new cultural trends and ideologies.

Parisian Arcade Street

Philosopher Walter Benjamin, in his work Arcades Project, observed that the bourgeoisie would dress elegantly and wander the streets, screening the diverse shop windows for new products and services. They seemed to approach the city with a botanical collector’s curiosity, searching for fresh experiences.

Coffee shops became gathering places for this new middle class. In the late 18th century, there were only three coffee shops in Paris, but by the late 19th century, they were ubiquitous, with some being as luxurious as the Notre Dame Cathedral.

Interestingly, Walter Benjamin noticed that those sitting in coffee shops had a peculiar attitude. On one hand, they kept a distance from urban space, observing pedestrians through the windows, and scrutinizing others’ attire and lifestyles. On the other hand, they allowed outsiders to see them inside through the windows, indifferent to the gazes of passersby, taking a moment to self-admire in the reflection on the glass. This peculiarity wasn’t inherent in human nature but rather a survival strategy derived from the modern social environment.

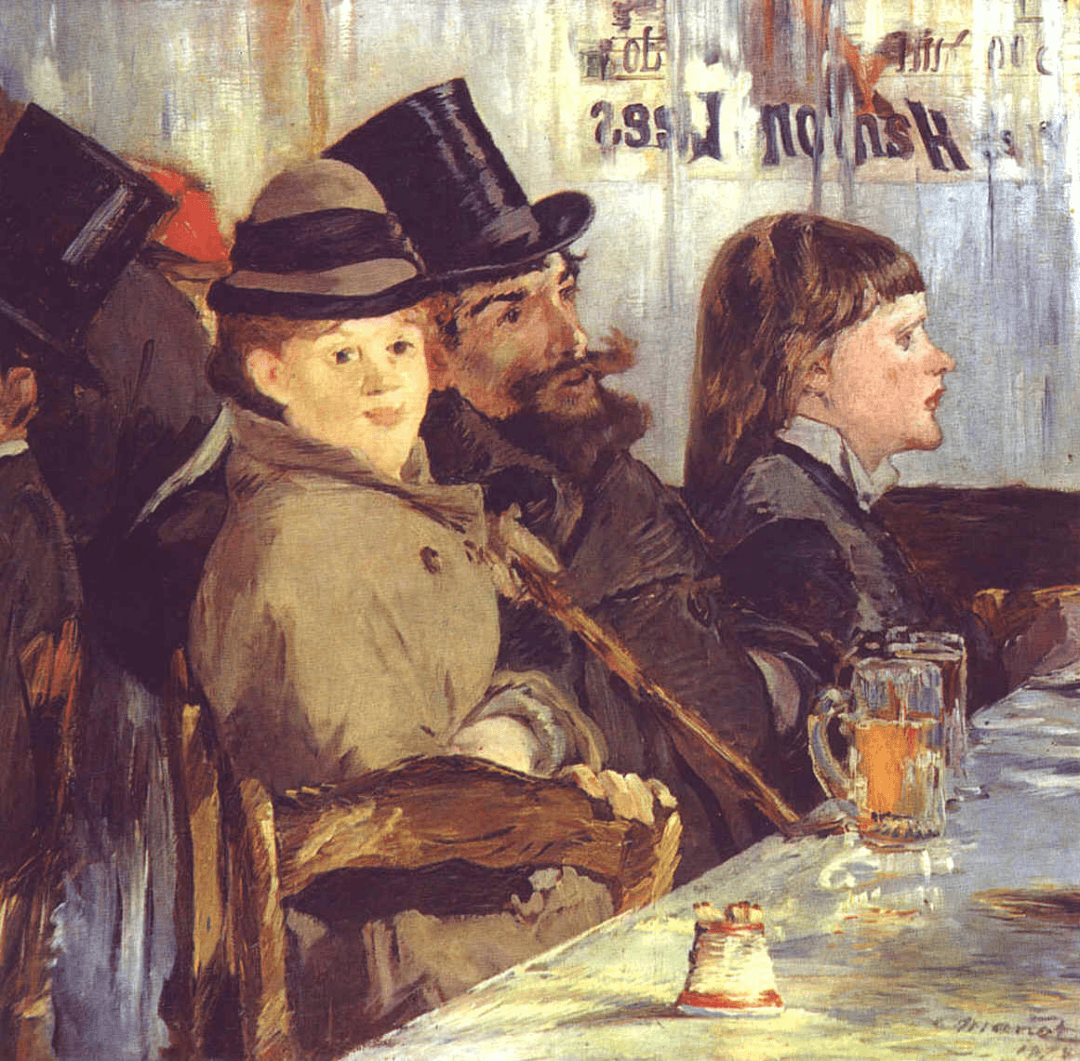

“At the Café” by Edward Manet, 1878

German sociologist Georg Simmel analyzed that as modern individuals freed themselves from feudal constraints, gaining equality and freedom, they found themselves exposed to a city filled with strangers. To differentiate themselves in a society nominally characterized by equality, they had to resort to clothing, occupational identity, or personality. The cup of coffee in hand became a “prop” for differentiation, and the coffee shop became the new runway.

It’s also worth noting that the fame of Parisian cafes also stems from the many open-air establishments on the left bank of the Seine being gathering places for world-renowned figures. Hemingway, Gauguin, Monet, Sartre, and de Beauvoir, these famous artists and philosophers have all sipped exquisite French coffee in Parisian cafes, and they have made places like Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots sought-after destinations for many. Even in modern society, Parisian cafes have their distinct traits. Romantic and bourgeois cafes often appear in various travel guides, attracting more people to visit.

Seattle: Home of Starbucks and Playground for IT Elites

In 1987, Howard Schultz faced a significant challenge. At that time, while still managing “Il Giornale,” he had an infinite passion and vision for the coffee industry. He sees coffee shops as a chain-like and comfortable third spaces. In his quest to expand his business, he was preparing to acquire his former employer – Starbucks.

Within 90 days, Howard needed to raise $3.8 million. However, a formidable competitor also led him to come to nothing – Bill Gates. The person who came to Howard’s rescue was none other than Bill Gates’ father, William Gates. Moved by Howard’s entrepreneurial enthusiasm, he introduced Howard to Bill Gates and convinced him to abandon direct investment, instead assisting Howard in the acquisition.

This story may be a coincidence, but in reality, the development of the internet industry in the 1980s is inseparable from the growth of chain coffee shops like Starbucks. Similar to how the elites in Paris cultivated cafe culture, Starbucks’ success is tied to the changes in American society in the late 1980s.

At that time, American society was undergoing a transition, having experienced the first baby boom and the decline of the counterculture hippie movement after the Vietnam War. The recession in manufacturing impacted blue-collar culture, while the booming IT industry gave rise to a new mainstream group – the Yuppie (Young Urban Professional). Yuppies, born in the late 1950s to 1965, were different from the previous generation that grew up under the revival of war. They did not experience the rebellious Woodstock protests against the Vietnam War. Their political consciousness was more conservative, embracing a consumption culture under new liberal economics. With high education and income, they moved to cities on the West Coast after graduation, becoming a new generation of the American upper-middle class.

The growth of the Yuppie population marked a crucial turning point for American coffee culture. Before Starbucks became popular, Americans viewed coffee as a daily functional beverage, brewing instant coffee in large containers with a bland taste. Coffeehouses at that time were closely associated with blue-collar culture, serving as meeting places for blue-collar workers. Folk singer Bob Dylan also emerged from these coffee shop performances, singing, “One more cup of coffee for the road, one more cup of coffee before I go.”

Functional large-package instant coffee Folgers

The appearance of Starbucks decoupled coffee culture from blue-collar culture and reconnected it with the elite culture centered around Yuppies. Starbucks’ hometown, Seattle, led this transformation and popularized American coffee culture globally.

Starbucks’ presence in Seattle was not accidental. This city is also the birthplace of new-generation internet companies like Microsoft, Amazon, T-Mobile, and Expedia. The rise of the IT and internet industry drove the global information revolution, significantly boosting productivity through technological innovation. The cross-industry interaction and the empowerment of technological thinking brought IT elites to the forefront of history. Unlike traditional white-collar workers who mainly communicated in workplaces, Yuppies and IT elites also needed spaces for offline interaction. Starbucks advocated the “third space,” referring to the space between home and workplace, which became even more essential for Yuppies and IT elites.

Starbuck’s first store

The rise of the internet economy facilitated Starbucks’ rapid expansion on the West Coast, entering the fashion-forward city of Los Angeles and eventually spreading throughout the United States. The population’s mobility accelerated Starbucks’ growth, as cities like Seattle on the U.S. West Coast attracted many migrant workers. Many Yuppies gathered here, moving from their hometowns to metropolitan areas where technology companies were concentrated. Coffee shops accompanied population migration, and today, Starbucks stores can be found in almost all airports.

Yuppies and 19th-century Parisian middle-class individuals share a similar consumer mentality. Starbucks also provides customers with “social props”: cups for takeaways, large floor-to-ceiling windows, luxurious and comfortable spaces, and cup names that one may not know how to pronounce. Through the interaction of gazes inside and outside the store, they repeatedly confirm, ‘I belong here.’

Yuppies and IT elites contributed unique brand momentum to Starbucks. They were Starbucks’s most original atmosphere setters, aligning with the underlying logic of symbolic consumption: You are what you purchase. Consumption has become a means to define populations, and this unconscious means has turned into a purpose, leading people into an endless pursuit game.

Coffee shops found new consumers in modern America, the darlings of the internet age under neoliberal economics.

Changes on Tokyo Streets: Resting Lounge for Office Ladies

In 1992, Howard Schultz, who opened the first Starbucks store in Los Angeles, received a personal letter from Suzuki Rokusan, the founder of Japan’s fashion group Shazaby Alliance, inviting him to bring Starbucks to Japan. However, after analyzing and conducting research, Starbucks’ consulting company concluded that entering Japan might not be a wise decision. The representative of the investor in Japan’s fashion group, Tatsuo Umamoto, also doubted Starbucks’ positioning due to the market conditions in Japan at that time.

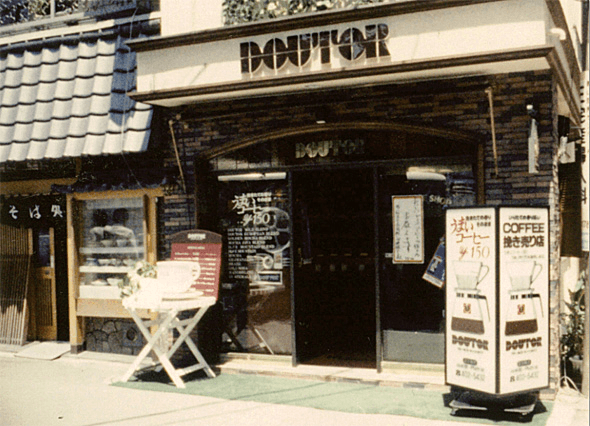

In the 1990s, coffee had saturated the Japanese market and entered a phase of decline. In 1981, Japan had 150,000 coffee shops, which decreased to just over 100,000 by 1991. Old-fashioned, high-priced pour-over coffee shops gradually disappeared in the market with intense competition. The winners of that era were high-quality, low-cost chain coffee shops, represented by Doutor, the counterpart of McDonald’s in China. Doutor rapidly expanded in major cities like Tokyo, offering high-quality, inexpensive coffee, priced as low as 180 yen (about 1.6 dollars). The main consumers were white-collar workers above 30, spending about 15 minutes in the shop, strategically located in high-traffic areas like train stations, serving as convenient refueling stations for essential consumers.

To maintain low-priced coffee, chain coffee shops like Doutor focused on optimizing store operations and promoting automation, standardization, and scaling. Under Doutor’s high-quality and high-turnover model, each store consumed a maximum of 2 tons of coffee beans per month, far exceeding the industry average of 20 kg to 50 kg. To control supply chain costs, Doutor established its coffee bean farm in Hawaii when reaching approximately 750 stores.

To further increase per customer transaction, value-for-money chain coffee shops like Doutor devoted efforts to developing desserts and meals. For example, Doutor’s flagship product was the sausage hot dog, priced at approximately 400 yen (3.6 dollars) when paired with coffee. Saint Marc Café did so by selling horn-shaped bread at about 120 yen (about 1.1 dollars). Combining high-value coffee with food/desserts became the standard strategy for most coffee shop chains in Japan.

Doutor’s first store

In a market where low-priced coffee dominated pricing, Starbucks’ prices were considered excessively high. Achieving Starbucks’ values (decoration, taste, and service) while keeping prices at the same level as Doutor was challenging, and Starbucks’ turnover rate was much lower than Doutor’s. Additionally, the Japanese were not used to taking away coffee, making it difficult to estimate the revenue model for a single store.

Based on these analyses, project leader Tatsuo Umamoto showed his pessimistic concern when he was in Starbucks headquarters. This made the then-executive director Howard Behar turn red, hurriedly explaining the operation of the store and the concept of the third place. “The atmosphere here, background music, high-quality products, the relationships between each staff and customer. These are all unique!”

Starbucks Ginza Store, Japan’s first store

Just as everyone hesitated on how to launch Starbucks in Japan, the founder of Shazaby Alliance, Rokusan Suzuki, bluntly stated while holding a Starbucks cup and looking at Umamoto, who was confused, “This cup and logo are extraordinary.” This statement suddenly reminded Tatsuo Umamoto of a Starbucks in downtown Seattle. At the entrance stood a green logo, and customers leaving the shop all held a cup with the logo, walking confidently on the sunlit street. Their posture was very stylish and cool, a lifestyle and scene he had never seen before. He suddenly realized that Starbucks carried not just coffee but everything behind the brand – the time, space, and air that people yearn for, which all evoked the imagination of consumers.

So, who were the consumers of Starbucks coffee in Japan? Conducting consumer surveys with his team, Tatsuo Umamoto interviewed individuals without mentioning Starbucks’ name but described the space of the store. Consumers were then asked to provide an acceptable price range based on their imagination of a coffee shop. They ultimately discovered that more than 60% of female consumers, as opposed to white-collar male consumers pursuing essential coffee, were willing to pay twice the price of Doutor for Starbucks coffee.

These women who were willing to pay a high price became the new generation of female white-collar workers in Japan. In 1985, Japan’s Equal Employment Opportunity Law for Men and Women was passed by the National Diet and officially implemented in 1986. The law guaranteed women the right to enter the workforce, leading to more white-collar women taking on executive roles within companies. Traditional Japanese coffee shops and Doutor coffee shops primarily attract male customers, with dark-colored interiors, smoking allowed, and coffee as the main product. With the advent of gender equality movements, women entering the workforce sought their own spaces.

To meet the needs of these demographics, Starbucks implemented a series of localized adjustments in Japan. In terms of interior space, Starbucks became the first coffee shop in Japan to implement a smoking ban. In terms of products, they strengthened offerings such as Matcha Frappuccino and seasonal limited-edition beverages. In retail, they expanded into a range of peripherals and began selling coffee beans. These strategies firmly grasped the female white-collar demographic as the core consumers. Young mothers also willingly come to Starbucks to relax and socialize, often pushing baby strollers. The mature and sophisticated decor of the stores also made Starbucks an attractive destination for high school girls.

As a “social prop,” Starbucks also attracts the younger generation of consumers. The prevalence of Western-style male and female baristas in Starbucks contributes to the perception of Starbucks as a fashionable and beautiful benchmark. Japanese university students are even willing to work at Starbucks. A Japanese retail expert mentioned, “White-collar workers strolling down the street with Starbucks cups had a significant impact on us. We realized that coffee could be enjoyed in this way.”

Starbucks successfully navigated the saturated market in Japan, capitalizing on the dividends brought about by changes in social structure. Through branding efforts, Starbucks gained the affection and trust of female consumers, overturning the industry trend that coffee must be sold at a low price and carving out its own niche.

Performance comparison of Starbucks and Doutor

Outlook: The Rise of Creative Talent in China

A century ago, Shanghai witnessed the birth of China’s first coffeehouses. Today, many first-tier cities in China have completed the market education for the coffee category. Chains like Starbucks have cultivated a mature base of coffee consumers. High-value-for-money coffee brands like Manner and Luckin continually drive repeat purchases among essential consumers. In what seems to be an incremental market in China, the core business districts and office spaces are witnessing intense competition.

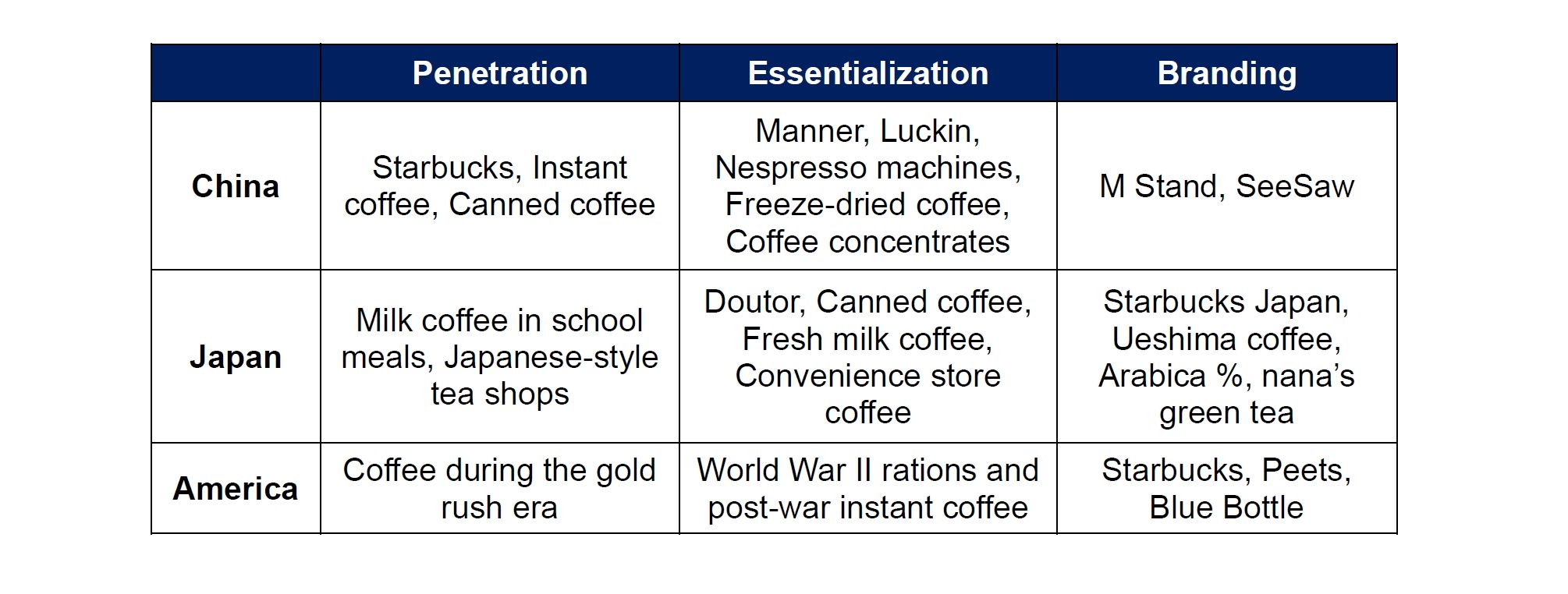

Three stages of coffee brand development

Observing the coffee market over a longer timeframe reveals that this category undergoes three stages: penetration, essentialization, and branding. The birth of domestic high-value-for-money coffee brands in China shares similarities with the trend of many cost-effective coffee shops like Japan’s Doutor in the 1990s.

In mature markets, consumers choose based on their needs. A consumer in Shanghai shared in an interview how they selectively consume diverse coffee offerings in different scenarios:

- Nespresso capsules for mornings at home

- Starbucks breakfast before work

- Starbucks for meetings, although it might be noisy

- Occasionally queue at Manner for coffee on busy days, maybe opting for a drip bag

- Order M Stand’s oatmeal cookie coffee during afternoon tea

- If there’s an important decision in the evening, they’d find a quiet coffee shop to think…

Undoubtedly, capsules, drip bags, and take-out coffee meet the needs of essential consumers. However, the spatial attributes of coffee shops hold significant cultural and social value in modern urban settings.

Consumer of M Stand with doodles on a MUJI bag

In our research on boutique coffee consumers, we found that regardless of age, profession, or income, these individuals possess creativity and independent thinking. They focus on the originality of their work, have independent aesthetics, enjoy trying new and beautiful things, and actively interact with consumption and life. Every detail of life and consumption becomes a source of inspiration for their work. Many are trendy white-collar women who require space and time for solitude, thinking, and relaxation. They belong to the “creative class,” a term coined by renowned urban studies scholar Richard Florida, representing those whose creativity and knowledge contribute to industries such as consumption, design, information, research, and finance.

These creative talents are not distant. Whether it’s a brand design draft, a comprehensive analysis report, or a meticulous work plan, these outputs require varying degrees of creativity from workers. They are consumers and producers of information, transforming various daily inputs into their own productivity through internal chemical reactions.

For those whose core productivity revolves around creativity, consumption is not just about goods; it’s about subconsciously gaining new experiences and understanding through the consumption process. Their demand for coffee extends beyond socializing, relaxing, and flaunting; what they value most is the continuous new experiences and interactions brought by the brand.

Represented by M Stand, boutique coffee brands are precisely aligned with this demographic. They differ from high-value-for-money coffee and traditional coffee shop chains, offering an entirely new coffee experience. For example, the innovative coconut iced coffee and oatmeal cookie coffee provide a fresh interpretation of coffee. The diverse store designs, tailored to each location, allow people to experience different spatial atmospheres. The company’s internally open culture encourages employees with creative thinking to freely develop and try new models and products. These capabilities create a match between product, audience, space, and corporate culture, offering consumers invigorating coffee, surprising experiences, and better production and lifestyle.

Aesthetic coffee space

Taking a historical perspective, the essential conclusion of this article is that every emerging coffee brand is accompanied by an upgrade in economic structure and changes in the mainstream consumer population. These individuals often represent the latest form of labor.

From a wide-angle view, creative talents have become the driving force behind China’s upcoming industrial upgrade. China’s economy is transitioning and gradually maturing. Internationally, China is shifting from low-value-added manufacturing to high-value-added industries such as high-end manufacturing, information technology, and new consumer industries. In the new economic model, creativity has become a new factor beyond the three traditional production elements of land and materials, labor and technology, and capital.

As China’s economy develops and transforms, we believe there will be larger groups of creative talents. The coffee shop market of China, under the trends of branding and iterative changes in consumer groups, will witness the emergence of coffee shops with global capabilities. Adapting to the transition of consumer groups, the new generation of brands in China will create unprecedented value and products.

References

- Alvin Toffler, The Culture Consumers

- Andrew Weil & Winifred Rosen, From Chocolate to Morphine: Everything About Addictive Culture

- Bob Dylan, One More Cup of Coffee

- Walter Benjamin, Arcades Project

- Georg Simmel, Metropolis and Mental Life

- Howard Schultz, Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time

- Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class

- Hiromichi Toriba, Doutor Coffee: The Entrepreneurial Story of Life and Death

- Toru Uesaka, Why Do Consumers Unconsciously Walk Into Doutor?

- Ryotaro Mebon, Japan Starbucks Story: The Challenge of Personalized Organization

- Aki Takada, Sociology of Hobbies

- Masatoshi Sasaki, The Challenge of the Creative City: Towards a City that Nurtures Industry and Culture

Internal Research Materials:

- Starbucks in Japan: From Zero to One

- Becoming a Popular Beverage? Analyzing the Popularization Process of Coffee in Japan

- Understanding Doutor’s Success from the Perspective of Michael Porter’s Competitive Theory and Three Turning Points