In recent years, the topic of "Mergers and Acquisitions" has been gaining momentum, sparking a new wave in China's capital market.

Youngor took over Intime, while MINISO acquired a controlling stake in Yonghui… Looking back over the past few years, China's consumer sector has seen numerous exciting M&A cases. For instance, ANTA successfully revitalized FILA and later propelled brands like Arc'teryx and Salomon to success, demonstrating textbook-level expertise in mergers, acquisitions, and brand operations.

Clearly, China is now experiencing yet another surge in M&A activity.

In contrast, developed countries such as the United States, Europe, and Japan have long completed efficient industry consolidation through numerous M&A, giving rise to large multinational corporations.

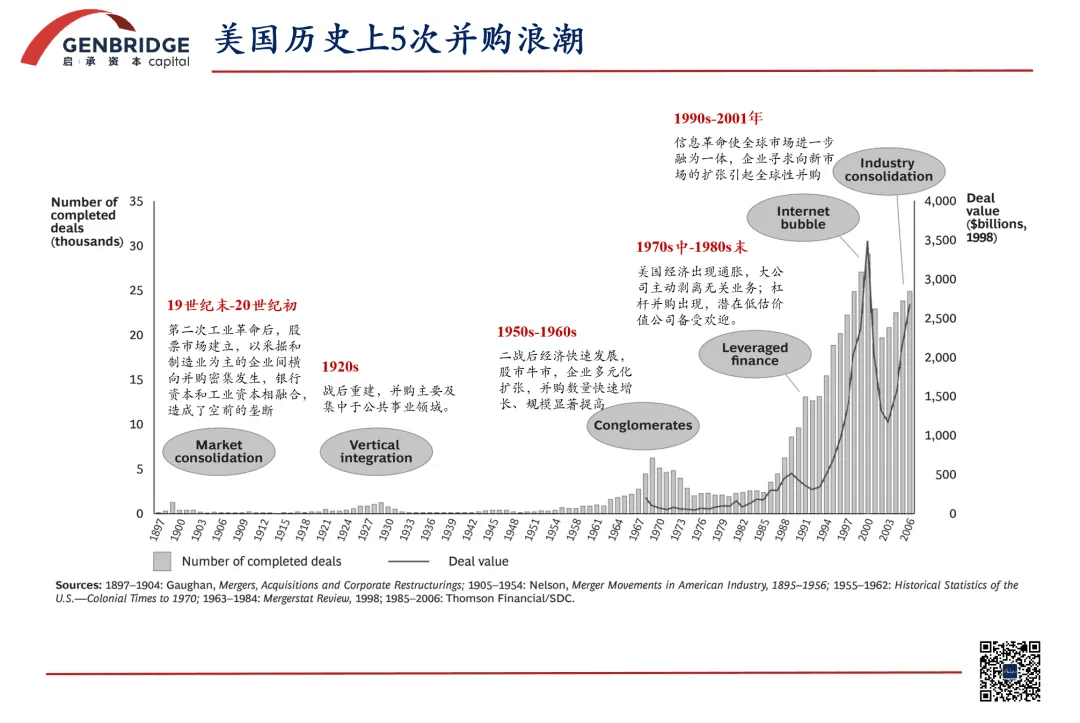

Over the past 100 years, the U.S. has undergone five major M&A waves, each of which has significantly driven economic growth and reshaped industry structures. Similarly, during the 30 years of the Heisei era, Japan leveraged M&A to restructure traditional industries and establish a global capital presence, laying a solid foundation for its strong economic recovery after 2010.

GenBridge Capital has been closely following this trend. In our view, the next two decades will mark a “big era” of “small-scale” M&As in China’s consumer sector.

As a consumer specialist VC, we have accumulated extensive industry resources and will continue to leverage our platform advantages to contribute to the efficient consolidation and long-term development of China’s consumer industry.

The era of seller emergence

Despite slowing economic growth, now is an optimal time for M&A — because this is an era marked by the emergence of sellers.

Around 2012, China’s high GDP growth rates of 6-7% or higher annually left little appetite for selling businesses. Companies with optimistic growth expectations would be unwilling to sell unless offered exceptionally high prices. Those willing to sell often face operational challenges.

Over the past three years, however, a critical shift has occurred in China: there are now sufficient sellers with strong motivations to exit. This stems from three key drivers:

- Non-operational factors driving exits Many sellers are motivated by non-business issues, such as the lack of successors.

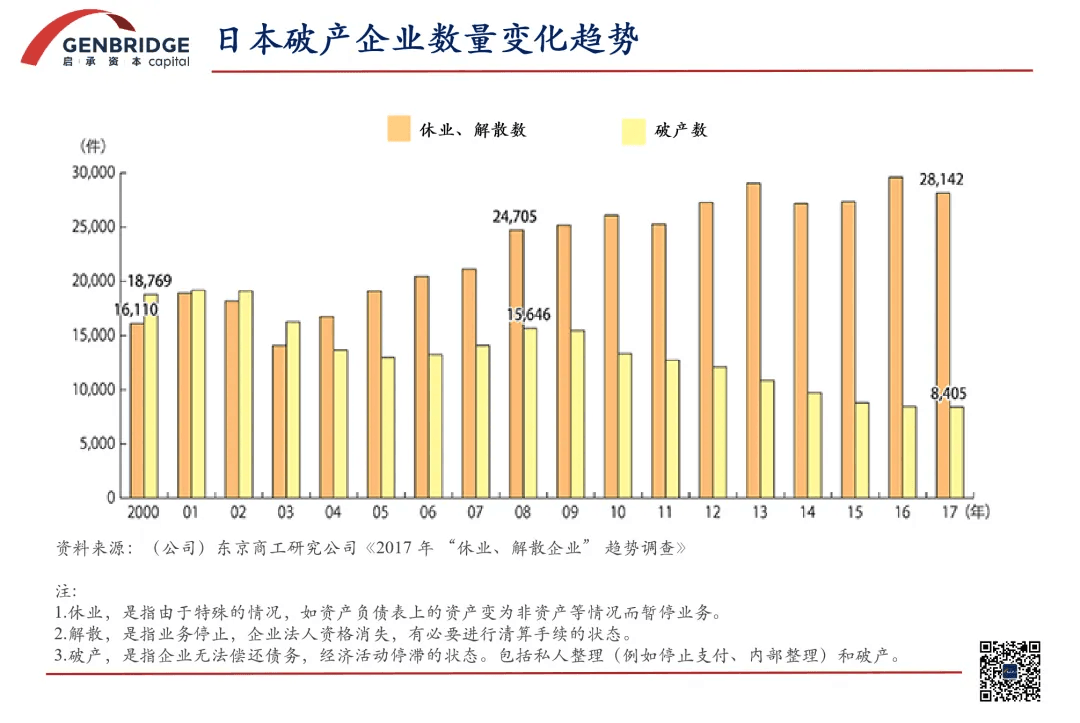

Post-2008 Japan saw a similar trend: bankruptcies declined, but voluntary business dissolutions surged due to aging founders, health issues, and succession gaps.

- Operational challenges Businesses face pressures such as stagnant growth (single-digit annual increases), aging teams, and intensified competition in saturated markets. As industries shift from competing for growth to battling for market share, operational stress rises, prompting owners to exit.

- Capital structure dynamics VC/PE investments over the past decade have reshaped equity ownership in many companies. Unlike traditional family-owned businesses, these entities face time-bound exit pressures from investors. Additionally, the difficulty of exiting via IPO further fuels M&A demand.

From the seller’s perspective, consumer sector assets awaiting exit have yet to peak and will continue growing. 95% of consumer companies would be difficult to IPO, yet these mid-sized firms — such as those with RMB 500 million in revenue and RMB 50 million in profit — represent the backbone of the industry. A decade ago, such companies could go public, but today’s stringent listing requirements leave M&A as their most viable exit.

Historically, IPOs symbolized social prestige. Today, businesses increasingly recognize their inability to meet listing standards despite being profitable. Against this backdrop, the three catalysts above are accelerating the willingness of mid-sized companies to sell.

The structure of the entire market has changed

The next 20 years will usher in a major era of small-scale M&A in the consumer sector—where "small" refers to companies that lack the capacity to IPO independently.

Currently, typical M&A targets in the consumer space include factories with revenues under RMB 500 million and profits around RMB 20-30 million. A recent example is ENXICUN, a supplier in the upstream supply chain, acquired by the parent company of Oreo.

Why are factories relatively attractive targets? Because small-scale M&A faces two key challenges: tradability of assets and buyer demand.

On tradability:

- Gold is easy to trade—once authenticity is verified, pricing is transparent.

- Real estate is slightly more complex.

- Companies are the hardest to transact.

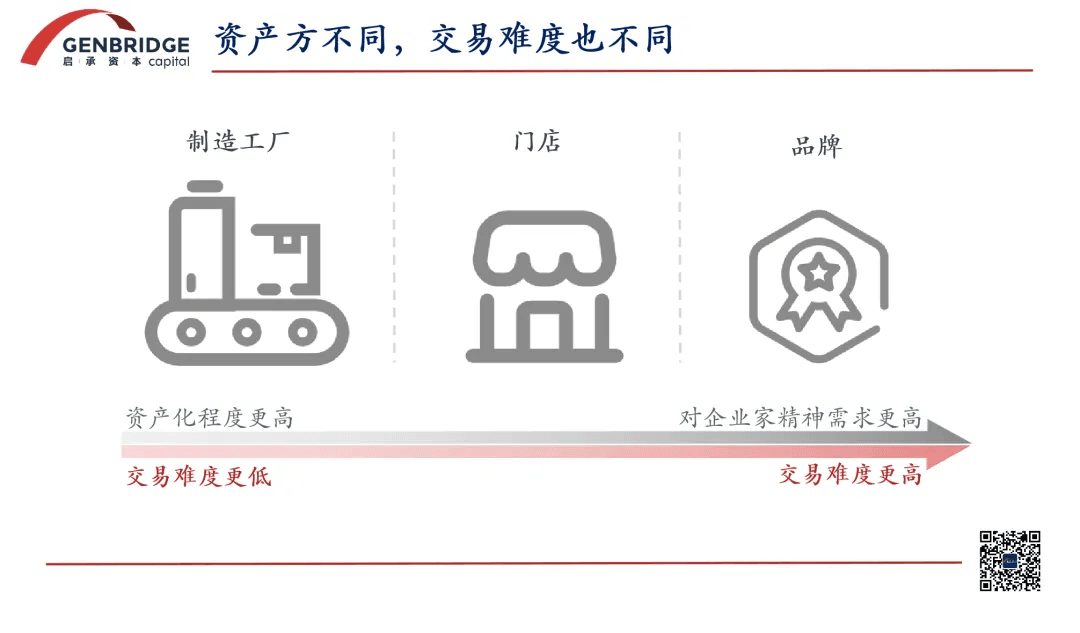

Companies can be categorized along different dimensions. Generally, the more asset-heavy a business is, the easier it is to trade, while those requiring entrepreneurial spirit and innovation are harder to transact. Between asset-heavy operations and entrepreneurial ventures, there are three tiers:

- Manufacturing factories (most asset-heavy, easiest to trade)

- Retail stores

- Brands (hardest to trade)

Input-output dynamics of stores are more predictable (e.g., rent, labor costs) than brands. The challenge lies in maintaining operational efficiency and adapting to changes.

In store investments, even non-institutional but professional investors—like many franchisees behind MINISO—systematically reinvest profits into new stores after initial success. This kind of structured, scalable innovation is worth encouraging and represents a significant breakthrough from an entrepreneurial perspective.

Brands require continuous investment in brand-building. Small and mid-sized brands in M&A face an awkward dilemma: they lack the scale to hedge brand-building risks. Thus, they are better suited as bolt-on acquisitions by larger corporations (e.g., P&G acquiring niche brands).

From buyer's perspective, China’s market has shifted from high-growth to saturation. While structural growth opportunities still exist, systemic growth has slowed significantly, leaving many companies stagnant.

As a result, buyers are adjusting their investment strategies to align with the changing supply of assets in the market.

The trend is clear: the proportion of non-growth (stagnant) assets with sale intentions is rising. In the past, high-growth companies dominated, with strong financing demand and minimal exit interest. Today, high-growth firms are far fewer, while sellers multiply. In a stagnant economy, internal optimization becomes essential.

Why M&A?

- Controllable cash flow (typical payback period: 3-5 years).

- More exit options (e.g., selling to strategic buyers after value enhancement).

- Less reliance on IPO markets, making it more SME-friendly.

Thus, the entire market has strong incentives to pursue M&A.

Globally, nearly all major consumer giants—from L'Oréal and LVMH to Haier’s global brand acquisitions—have grown through relentless M&A.

Small and mid-sized M&A will follow this trend. In the U.S., for instance, the capital market is dominated by M&A (80%) rather than growth-stage investments (20%), reflecting asset-side demand. Today, there are already ~2,000 GPs specializing in small to mid-sized M&A in the U.S.

The historical role of buyout funds

In overseas M&A strategies, one of the most effective approaches is the platform strategy.

For example, if a buyout fund aims to consolidate food factories, it can establish a holding platform through an initial acquisition and then continuously add more deals, leveraging accumulated expertise. The goal of building such a platform isn’t just to address the challenges of a single RMB 300-500 million company but to solve similar problems across ten comparable businesses. This is where the platform’s value lies for SMEs.

Large corporate buyers prefer highly asset-heavy companies, but in reality, many businesses are not in a readily tradable state. This is where small and mid-sized buyout funds play a crucial role overseas—they acquire businesses in their raw form, optimize their structure to make them more asset- or capital-efficient, and then sell them to strategic buyers.

Large buyout funds, on the other hand, often act like oncologists. When a company grows too large, inefficiencies—like cancerous cells—begin to spread. These funds step in, perform "surgery" (restructuring), and then exit. Essentially, they address systemic inefficiencies within industries. However, China’s market is not yet mature enough for this model.

The biggest difference in China lies in its developmental stage. With a relatively short economic growth cycle, China’s corporate ecosystem hasn’t reached the level of maturity seen in Western markets. There simply aren’t many large, ownerless enterprises ripe for buyouts.

Instead, a more common scenario involves a founder in a Tier 3 or 4 city owning five to ten retail stores or a supermarket chain with RMB 600 million to 1 billion in revenue and RMB 30-40 million in annual profit—but with no successor. This is a widespread issue in China.

These SMEs often suffer from low talent density, regional constraints, and insufficient backend investments (e.g., IT, supply chain), leading to unrealized operational efficiency. The core mission of industrial buyers in small and mid-sized M&A, therefore, is to resolve these inefficiencies.

Future small and mid-sized M&A will likely follow a platform-reuse model, driven by two emerging buyer groups:

- Next-gen industrial corporations

- Next-gen buyout funds

In this environment, funds partially assume the role of FA. While FA cover a broad range of deals with low success rates, thematic platform funds can focus more narrowly, increasing investment certainty and efficiency—effectively internalizing some FA functions.

Most fund managers lack deep industrial knowledge. Building a platform requires comprehensive operational capabilities, traditionally limiting funds to niche sectors. However, in recent years, financial funds have been striving to industrialize—a positive trend that could enhance sector-wide efficiency.

What's the next step?

Genbridge Capital specializes in growth-stage investments while also deeply engaging in post-investment management. Through this process, we have accumulated substantial experience in addressing operational shortcomings—experience that can be systematically replicated.

For example, a company with RMB 300-500 million in revenue may have underinvested in digitalization. However, GneBridge’s portfolio companies have scaled from RMB 500-600 million to RMB 10-20 billion, with our team actively supporting their IT transformation. This allows us to transplant proven solutions to smaller enterprises, helping them close critical gaps.

Another example is large-scale procurement. Across our retail investments—spanning five to six companies, 30,000 stores, and RMB 70 billion in revenue—we’ve forged strong partnerships with top-tier suppliers. These relationships can be extended to smaller players, granting them access to resources typically reserved for industry leaders.

Furthermore, many of our food retail portfolios rely on decentralized, small-scale factories (often with RMB 200-300 million in revenue) for customized production. While individually these factories lack scale, their collective potential is immense—mirroring the model of Japan’s 7-Eleven, which unlocked efficiency through supplier consolidation.

Leveraging our deeply embedded relationships across the retail value chain, GenBridge is positioned to extend this model: building an M&A platform focused on food retail and supply chain integration, driving optimization across China’s fragmented industry.

As China transitions to a stock economy, sellers are emerging en masse, marking just the beginning of a small/mid-cap M&A wave. The ecosystem, too, is taking shape:

- Corporates are learning to acquire;

- Funds are industrializing their expertise;

- Investment banks and FAs are refining their models.

Every player is carving out its niche—facilitating the economy’s renewal, elevating industrial efficiency, and creating commercial value.

This is the industry’s shared vision and the demand of our times. We anticipate China replicating the vibrancy of the U.S. small/mid-cap M&A market: 2,000-3,000 specialized GPs, active corporate buyers, and a dynamic advisory landscape. The stage is set for a parallel boom.