2024 was a challenging year for China’s consumer market. Amid workforce downsizing for efficiency, lowered income expectations, and a rising savings rate, some have suggested that “China's consumer confidence is declining.” At the same time, consumers are actively restructuring their spending patterns. For example, they postpone purchases of non-essential items; when it comes to necessities, priority is given to children and the elderly, while middle-aged adults settle for whatever is sufficient.

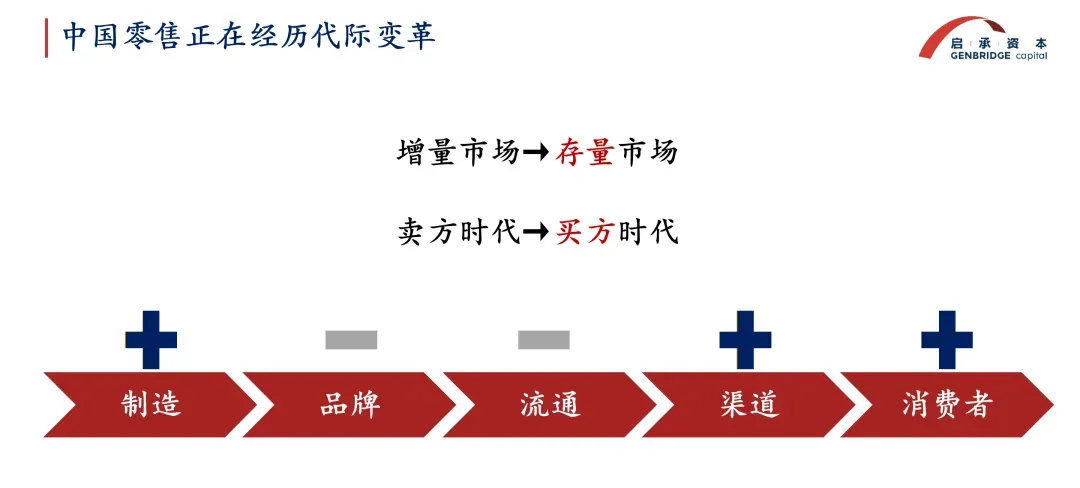

This shift signals a transformation of the consumer market—from an incremental market to a saturation one. In this intergenerational transition era, breaking through the status quo requires a methodological update: the shift from a seller’s market to a buyer’s era.

What is the seller’s era?

Over the past two or three decades in China, it was the brands that drove product R&D. Brand owners coordinated with manufacturers, forming tiered distribution systems to stack and push products to reach consumers.

Today, consumer demand is diversifying. Consumers want to know the story behind the product and to receive emotional value instead of only cheap goods. They now hold more power than ever. The channels that closest to consumers hold the advantage.

Channels understand what consumers really need. That’s why many of them are leading the transformation by producing high-quality products, offering strong value at accessible prices, expanding their retail networks with breadth and expertise, and delivering more satisfying experiences for consumers.This is the current evolution of China’s retail industry.

We will explore several domestic and international case studies to better understand the trends and key methodologies driving retail transformation.

“Everyday low cost” is the core of the discount retail model

In 2017, a man named Yan Zhou opened a bulk snack store. Seven years later, that store has grown into a retail giant with over 6,000 locations—Snack Is Busy (“零食很忙”).

This year, Snack Is Busy merged with another major player in the industry, Zhao Yiming Snacks. Together, they now operate more than 12,000 stores, making them the fastest brand in China to surpass the 10,000-store. Their total sales this year are expected to exceed 40 to 50 billion yuan. By historical standards in China’s retail industry, this would place them firmly in the Top 10.

At a time when the retail sector is under pressure, Snack Is Busy continues to thrive. So how exactly are they doing it?

1. Variety

Snack Is Busy stores are around 100 square meters in size and typically located near residential communities. Each store carries around 1,500 to 2,000 SKUs, densely packed on the shelves. Customers can find 20–30 types of spicy gluten strips, 40–50 types of chips, and a huge range of cakes, jellies, and chocolates, truly a wide selection.

Behind this abundance is expertise. Snack Is Busy’s buying team sources not only from major brands like Weilong and Spicy Prince, but also from local specialty producers around the country.

2. Affordability

A 330ml can of Coca-Cola might cost 3 yuan in a supermarket, or 3.5 yuan at a convenience store. But at Snack Is Busy, it’s just 1.8 yuan. Customers casually browse and buy, yet their total at checkout usually stays around 25–30 yuan. This is the essence of bulk discount retail.

Such low prices have sparked misunderstandings, with some assuming the company is selling at a loss. But in reality, Snack Is Busy has maintained healthy, sustainable growth.

So how do they make the discount model work?

Traditionally, when a consumer spends 1 yuan on a product, the manufacturing cost is about 0.3 to 0.4 yuan. The remaining 0.6 yuan goes to distribution and retail markup. However, innovative retailers like Snack Is Busy are breaking this model: they eliminate middlemen, purchase directly from factories in cash at base price, and require only one condition—pricing autonomy.

This way, consumers benefit from low prices, and retailers, with economies of scale, create a positive cycle of growth.

3. Convenience

Take Changsha as an example: in a community with just a couple thousand households, a Snack Is Busy store can open and thrive. Changsha alone already has 600 locations.

In just a few short years, Snack Is Busy has opened over 2,000 stores in Hunan Province alone, generating over 10 billion yuan in revenue—comparable to online snack giant Three Squirrels, whose revenue is also around 10 billion yuan.

The secret behind this rapid expansion is a highly efficient franchise system.

Snack Is Busy’s franchisee acceptance rate is only 1%. The model is low-cost with fast payback, leading to surging application numbers. Yet despite having over 10,000 franchised stores across China, the company maintains high operational standards.

Every store is monitored by 10–20 HD security cameras. Nearly 100 employees at HQ check store organization, product placement, whether staff greet customers...... All of these are part of a detailed scoring system.

For instance,a score drop of 15 points may trigger a mandatory temporary closure and retraining. Scores consistently above 90 can earn franchisees priority access to better locations nearby.

Beyond cheap, abundant, and convenient, Snack Is Busy understands how to “play”. In downtown Changsha, Snack Is Busy opened a flagship store called “Snack Is Big” (零食很大), offering exclusive, oversized products not found elsewhere. Right next door is “Snack Is Spicy” (零食很辣), a 200㎡ store with over 2,000 SKUs, all spicy snacks.

Shifting our focus from domestic to international markets, discount retail offers a wider array of innovative models and creative approaches.

Don Quijote, one of Japan’s largest retailers, is known for its “treasure hunt” shopping experience. Each store carries an astonishing 20,000 to 30,000 SKUs, all tightly packed together. Shopping there feels like an adventure, around any corner, you might stumble upon a luxury item at an irresistible price.

Kobe Bussan, a food supermarket transformed from a wholesale business. After the second-generation leadership took over, they adopted the slogan “low price but unique”, meaning every product must be not only inexpensive but also distinctive.

How do they achieve this? Primarily through acquisitions. Over the past decade, Kobe Bussan has acquired numerous upstream factories. About 1,500 of their suppliers are based in Shandong, China. Now it offers more than 3,000 frozen food SKUs, many of which are exclusive and unavailable elsewhere. Despite operating with a low gross margin of just 11.45%, the company maintains a net profit margin of over 4%—a testament to its highly efficient and differentiated model.

After looking at these standout cases, we can better understand the true essence of discount retail. Sam Walton, the founder of Walmart, proposed the concept of “Everyday Low Price” (EDLP). But behind the surface-level low prices lies something even more critical: “Everyday Low Cost.” This is the real challenge in discount retail. Achieving low costs requires companies to continuously scrutinize the entire supply chain and use various methods to eliminate inefficiencies. And doing that depends on ongoing innovation.

This type of discount model is expected to become one of China’s fastest-growing retail formats in the next 10 to 20 years.

The “manufacturing-retail alliance”: The secret to convenience store products

Looking back over the past 30 years of retail evolution in Japan, two formats have been declining: large supermarkets and department stores. Meanwhile, three formats have seen strong growth: discount stores, convenience stores, and drugstores. These growing formats solve consumers’ three biggest worries: fear of poverty, fear of illness, and fear of inconvenience.

Discount stores address the fear of poverty (as discussed above). Drugstores respond to the fear of illness. As for fear of inconvenience, no one does it better than Japan’s world-class convenience store industry.

Over the past 30 years, Japan’s convenience stores have grown nearly tenfold, from 5,000 to between 50,000 and 60,000 stores today.

Take 7-Eleven, one of the "Big Three" convenience store chains, as an example. A single 7-Eleven store in Japan generates around 500,000–600,000 yen (25,000–30,000 RMB) in daily revenue. Roughly 60–70% of the products sold are food-related. For many Japanese people, convenience stores are not just a place for snacks—they provide all three meals, plus afternoon tea, coffee, desserts, and late-night snacks.

So why is 7-Eleven so strong in the food category?

Its parent company, Ito-Yokado Group (which later formed the holding company Seven & i Holdings), is now the largest retail group in Japan. It also operates one of Japan’s largest supermarket chains, with around 15,000 food SKUs, 2,000 of which are exclusive to its convenience stores. Notably, 65% of these are private-label products.

What’s surprising is that, unlike most retailers that use private labels as cheaper alternatives to brand-name products, 7-Eleven flips that logic. For instance, while the average price of instant noodles in Japan is around 120 yen, 7-Eleven introduced a higher-quality version priced at 250 yen. And it doesn’t stop there—this approach extends to bread, ice cream, wine, and more. In recent years, 7-Eleven has even upgraded its mission and vision, positioning itself as a “world-class retail group with a focus on food.”

7-Eleven’s core secret to making great products lies in what it calls a “Manufacture-and-Retail Alliance.” In this strategy, “retail” refers to the store/channel, while “manufacturing” refers to upstream producers and brands. The two sides collaborate based on consumer needs to co-develop new products. Only by making products truly unique can the retail channel stay competitive.

This strategy is now being adopted in China’s retail industry. Take New Joy Mart, an invested company under GenBridge Capital, as an example. In Central China, New Joy Mart has over 1,000 stores and has developed a series of successful products over the past year.

This product was born out of the founder’s keen awareness of a low-price opportunity in the dairy supply chain. Due to an oversupply of upstream raw milk this year, prices dropped. New Joy Mart sourced premium raw milk from pastures in Ningxia, transported it via cold-chain trucks to Central China for processing, and got it on shelves in a short time. Each store now sells over 20 units daily, and the brand has become one of the top fresh milk options in the Changsha area, especially popular among blue-collar workers.

A similar story applies to their beer product, with 4.5% malt concentration and 11% alcohol content, priced at just 3.9 yuan. New Joy Mart partnered with a brewery in Xiangtan, using a “shared cold-chain delivery” model to split transportation costs. As a result, they launched a promotion of “3 bottles of 500ml beer for 9.9 yuan”, offering unbeatable value.

By offering value-for-money private brand products, New Joy Mart was able to open 15 stores at a time as it expanded into county cities, and the ability behind this was manufacturer–retailer alliance.

A new mainstream market of 900 million people is rising

Recently, Pang Dong Lai’s 'overhaul' of Yonghui Superstores has become one of the hottest topics in China’s retail industry. During this transformation, Pang Dong Lai demonstrated its strength in single-product (SKU-level) management. They delisted more than 10,000 products and introduced over 10,000 new ones.

This was a strategic shift. The products that were removed were non-standardized, mass-distributed, price-driven items. In contrast, the new additions were items loved by consumers and independently developed by Pang Dong Lai, such as ready-to-eat foods, baked goods, and frozen items.

This represents a major leap forward in retail operations in China. It breaks away from traditional supermarket practices based on category management, and instead adopts SKU-level management, which both enhances consumer value and maximizes profit per product.

In addition, Pang Dong Lai has introduced many improvements in retail operation techniques. For example, in its stores, salespeople from suppliers are not needed to explain products or persuade customers. The products themselves serve as content, and rich, detailed product information is enough to drive purchasing decisions.

Pang Dong Lai has achieved RMB 10 billion in revenue just in Xuchang and surrounding cities due to its innovative retail practices.

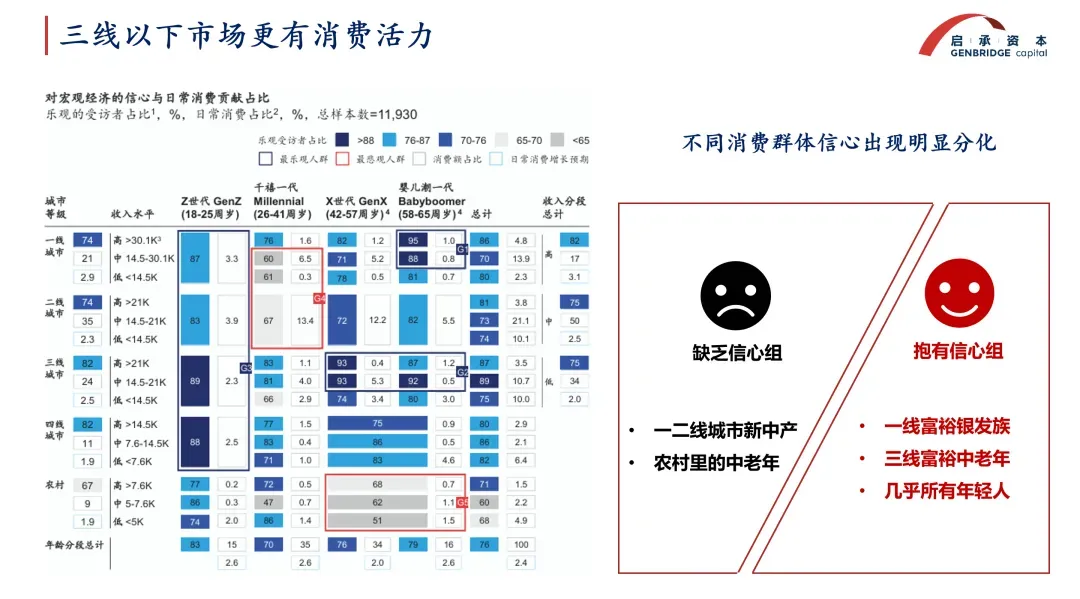

According to a recent McKinsey survey on Chinese consumers, while the spending confidence of new middle-class consumers in Tier 1–2 cities and middle-aged and elderly people in rural areas has declined somewhat, affluent older adults in Tier 1 and 3 cities, along with almost all young people, still have strong confidence in consumption. Many young consumers believe that as long as they don’t buy a house or get married, their cost of living is manageable, and they’re more willing to spend money on the things they enjoy.

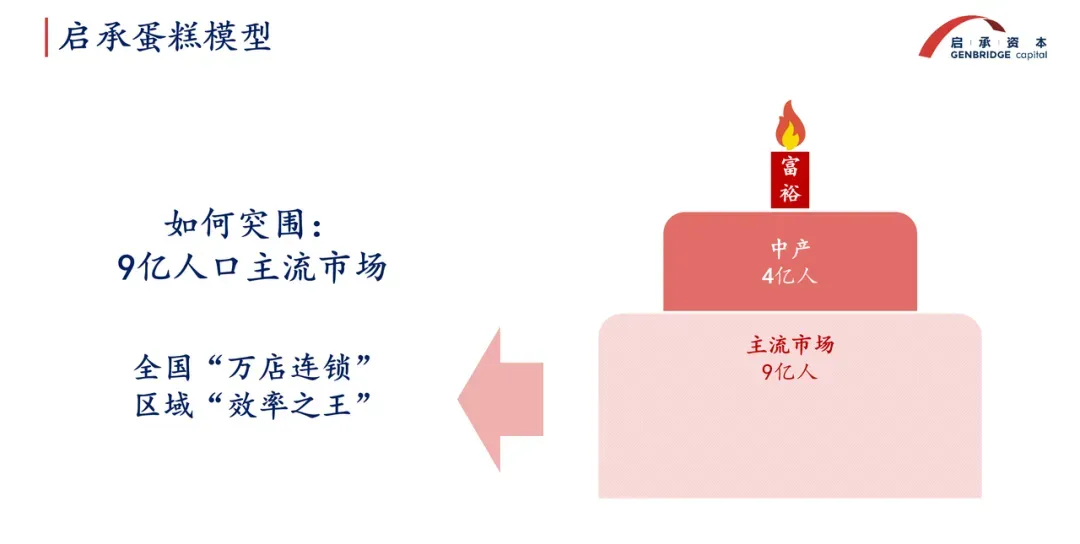

Over the past decade, China's consumer sector has mainly focused on the emerging middle class, a group numbering 300–400 million people.

But today, the most dynamic and vibrant consumers are concentrated in Tier 2, Tier 3, and lower-tier cities—a market of around 900 million people.

In just the past two to three years, Mixue Ice Cream & Tea has opened an additional 20,000 to 30,000 stores; Luckin Coffee added 10,000 new stores in a single year; chains like Snack Is Busy and Guoquan operate over two-thirds of their stores in Tier 3 or lower cities......

These examples clearly prove one thing: 900 million-person mass market is becoming the true mainstream of Chinese consumption—this is the real foundation for the future of China’s retail sector.

Conclusion: Three key takeaways

In this saturation era, where growth no longer comes from sheer volume but from transformation and optimization, retail companies looking to break through must focus on three core principles:

- High-efficiency business models:

The retail industry is and always will be an efficiency-driven industry. Efficient models will inevitably replace inefficient ones, in an ongoing cycle of evolution.

- Products with a strong value-to-quality ratio:

The heart of retail is no longer just superficial low prices, but rather a return to products that deliver true value for money.

- High-potential markets:

Pay attention to the most promising growth zones, especially Tier 3 and lower-tier cities—the 900 million consumers who are now becoming China’s mainstream market.