In recent years, with the rising popularity of healthy whole grains and high-quality carbohydrates, corn has emerged as a new favorite staple food alongside rice and wheat.

On Xiaohongshu, there are over 1.85 million posts under “#corn for fat loss.” Meanwhile, yellow glutinous corn went viral through livestreams by Oriental Selection, sparking a heated online debate over whether "6 yuan for a single ear of corn is too expensive."

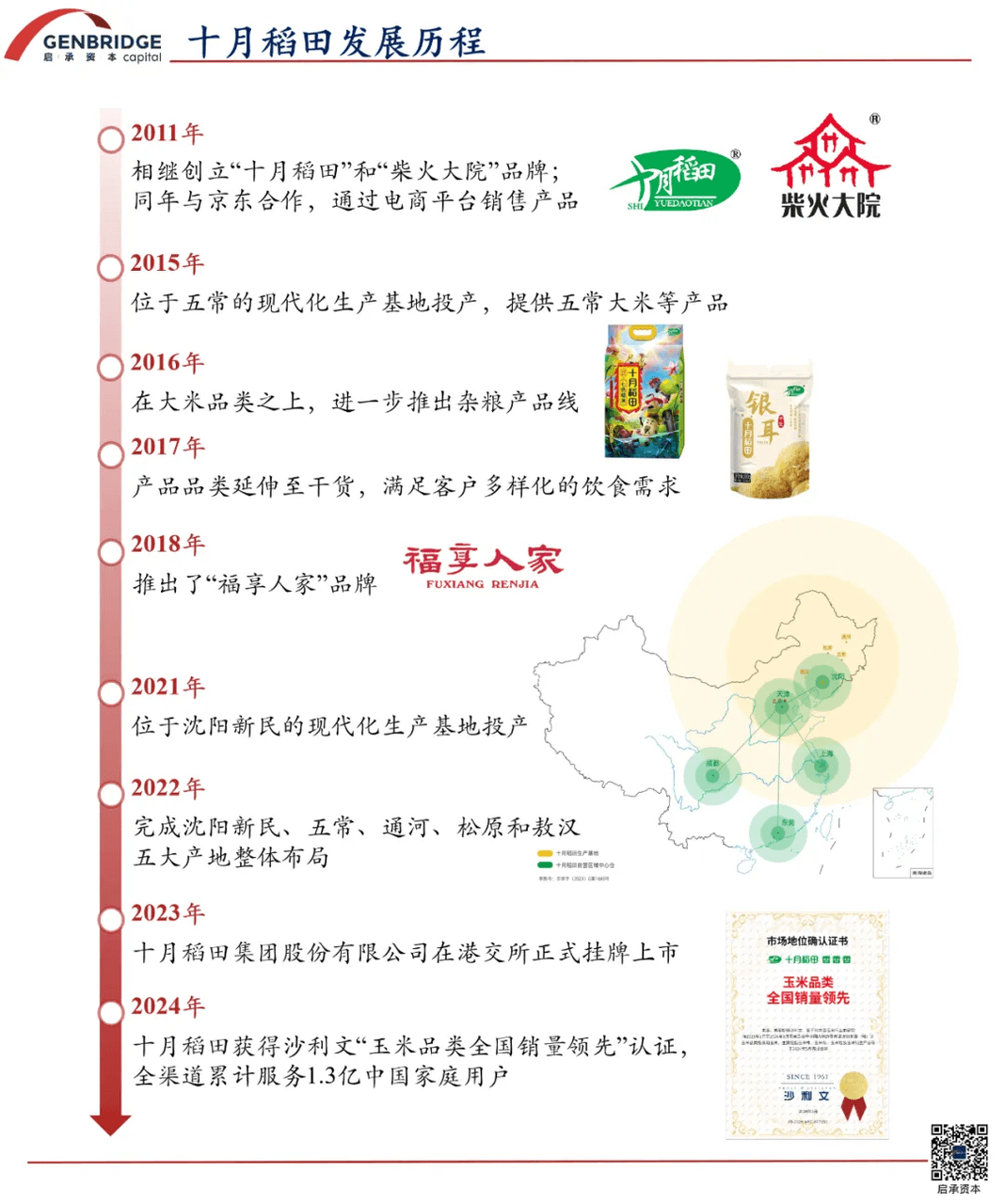

Corn has rapidly transformed from a basic agricultural product embedded in the national memory into a highly sought-after consumer star. Amid this lively consumption trend, Harvest (ShiYue DaoTian) has undoubtedly been the biggest winner.

In 2023, Harvest heavily promoted its yellow glutinous corn on Tik Tok. During the 2024 Chinese New Year shopping festival, Harvest’s yellow glutinous corn ranked among the Top 20 Best-Selling Products on Tik Tok, achieving both strong sales and a stellar reputation.

As of the end of June this year, a single product link for yellow glutinous corn at Harvest’s official Tik Tok flagship store had accumulated 11.34 million units sold within a year. On Tmall, the sales volume of the same corn product has exceeded 400,000 units, while on JD, Harevst’s corn also recorded impressive sales figures.

Harvest’s corn products have consistently dominated bestseller lists across major e-commerce platforms. In May this year, they were certified by Frost & Sullivan as the national sales leader in the corn category, having served a cumulative 130 million Chinese households across all channels. Currently, the corn category’s daily average sales revenue across all channels is approaching 5 million yuan, making it another blockbuster product line for Harvest, joining the ranks of their billion-level bestsellers.

According to the company’s recently released mid-2024 financial report, Harvest Group achieved a revenue of 2.62 billion yuan in the first half of the year. Notably, its corn products stood out, helping drive 726 million yuan in revenue from the "whole grains, beans, and other products" segment, representing a year-on-year growth of 151.9%.

Behind corn lies a massive market worth hundreds of billions of yuan. However, before Harvest entered the scene, there had yet to be a truly national leading brand in this category.

Traditionally, consumers either bought fresh seasonal corn from local supermarkets or “blindly” purchased corn from various regions without much regard for branding—varieties like Small Glutinous Cornfrom Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Sweet Corn, or Northeastern White Glutinous Corn.

In just one year, Harvest rewrote the history of corn being a "category without a brand," becoming the top choice for consumers nationwide. What exactly did Harvest do right?

The star of livestreaming rooms

As early as four years ago, Harvest had already sensed that the branding and commercialization of corn were accelerating, with consumer demand on the verge of explosive growth, while the entire production side of the industry had yet to begin any major upgrades or iterations.

Wenjun Zhao, founder of Harvest, once remarked: “Corn is actually a great category that can transition from being seen as a coarse grain to a staple food. The market opportunity right now is excellent.”

To seize this opportunity, Harvest first introduced a range of product innovations. They developed eight different product forms, including whole corn cobs, corn sections, corn kernels, and popcorn kernels, covering use cases from staple foods to snacks and complementary foods. To meet the demand for single-person meals and portability, Harvest also launched small-package designs.

Harvest’s yellow glutinous corn has garnered widespread praise across social media platforms, with many users commenting that they could "almost smell the fragrance through the screen." On JD, the product boasts an impressive 95% positive review rate.

On the surface, this success seems to stem from innovations in corn packaging and product format. In reality, Harvest has carried out a full-chain modernization of corn — transforming it from a basic agricultural product into a high-quality item that passes through farmland, factories, and finally onto dining tables.

At the core of this transformation is the commitment to creating a truly outstanding product, built around three key elements: premium origin, superior processing, and efficient distribution.

First, a good origin determines superior product quality.

In China, corn production is widely distributed, forming a general pattern of "sweet corn in the south and glutinous corn in the north." Among them, the Northeastern region (including Inner Mongolia) is the primary spring corn growing area, producing about 90 to 120 million tons of corn annually under normal conditions—around 40% of the national total—making it China’s largest source of commercial corn.

Harvest’s corn is cultivated exclusively in the prime zones of the Northeastern production belt. The black soil here is rich in organic matter, famously described as “an ounce of black soil yields two ounces of oil.” Crops grow under a one-season-per-year cycle with large diurnal temperature variations, all contributing to a uniquely sweet and glutinous texture that corn from other regions struggles to match.

Moreover, Harvest focuses solely on producing "fresh-eating corn," meaning the ears are harvested at the late milk stage and immediately vacuum-packed to lock in their shape, flavor, and moisture maintained at 55%-75%, making them ready to eat without further processing.

Compared to the more "raw" corn sold in traditional farmers’ markets, fresh-eating corn offers superior taste and is a more modernized, standardized agricultural product—easier to store, transport, and consume.

However, producing high-quality fresh-eating corn demands strict control over variety selection, cultivation methods, harvesting timing, and techniques, as well as stringent processing standards.

In Harvest’s case, the second critical step to preserving corn quality lies in their near-field harvesting, temperature-controlled storage, and on-demand processing system.

Wenjun Zhao once remarked that producing great corn is essentially a race against time.

This is because the optimal harvesting window for fresh corn is less than three days. After harvesting, corn must be processed and vacuum-sealed as quickly as possible to preserve its peak flavor and texture. To achieve this, Harvest has built automated factories adjacent to the planting sites, ensuring that the corn travels from field to factory in less than six hours.

After entering the processing facility, each ear of corn undergoes a meticulous series of procedures: inspection, husking, trimming, salting, repeated rinsing with purified water, blanching, preservation using food-grade oxygen-barrier aluminum film, vacuum sealing, high-temperature sterilization at 121°C, cooling, and more—amounting to dozens of steps. Due to advanced automation technology, the entire process is completed in the shortest possible time. Even after being vacuum-packed, the corn is left to rest for about 15 days to monitor for any leakage, ensuring maximum freshness and product stability.

Finally, Harvest's logistics network—comprising five self-operated regional distribution centers in Shanghai, Tianjin, Chengdu, Shenyang, and Dongguan, along with ten local warehouses—swiftly responds to orders, ensuring that the corn reaches consumers' tables within three to five days.

Starting from cultivation in the fertile black soil, through layers of selection and numerous meticulous processes, Harvest brings corn to the tables of consumers nationwide at the fastest possible speed. This journey from farm to modern, standardized commodity is a story of relentless refinement and uncompromising control over every detail:

Without highly efficient, automated factories located close to the growing fields, large-scale production of high-quality fresh corn would be nearly impossible. Without a strong and resilient supply chain, consistent supply would be unattainable.

Yet, transforming a standardized product into a blockbuster requires one final and most critical element: building a brand.

A truly national brand

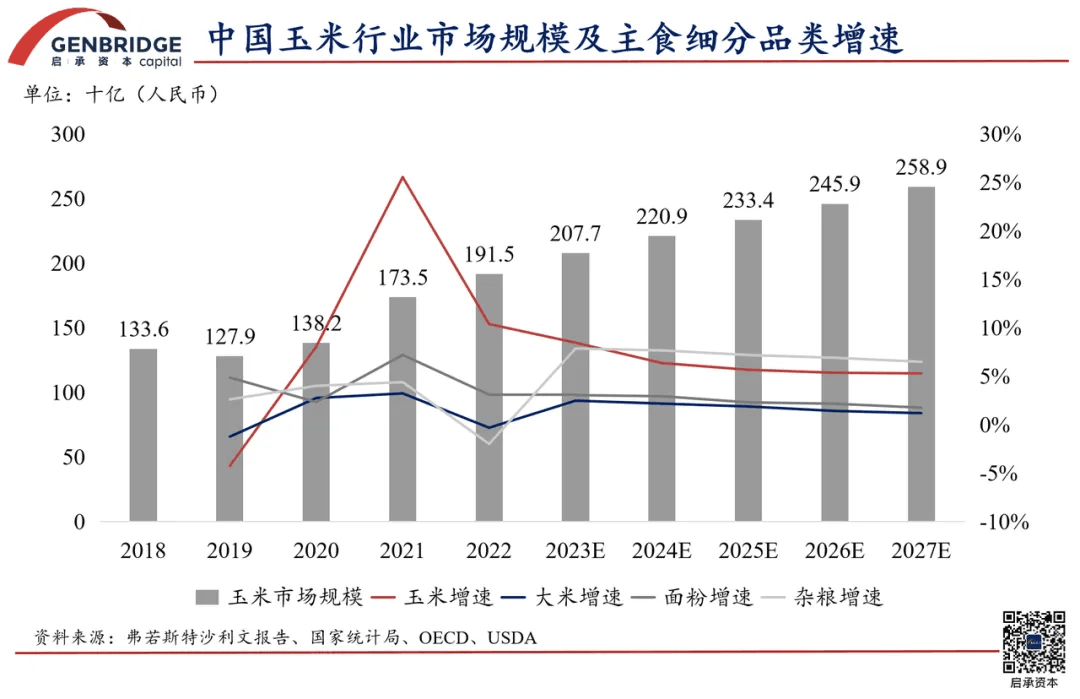

Research by the China National Food Industry Association shows that nearly 60% of consumers purchase corn or corn-based products at least once a month, and 15% have developed a weekly buying habit. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics and public sources, China's corn market achieved a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.4% from 2018 to 2022.

It is projected that by 2027, China's market size will reach 258.9 billion RMB, offering a golden opportunity for brands to grow into billion-level businesses.

However, for a long time, agricultural products like corn have faced the "category without brand" dilemma—while the market demand was strong and the variety abundant, no leading brand managed to dominate consumer mindshare in any subcategory.

Take the fresh-eating corn sector, for example: brands like Suihua Fresh Corn and Qinggang Corn from Heilongjiang, Jilin Fresh Corn and Siping Corn from Jilin have been well-established regionally, but none had yet emerged as a truly nationwide best-seller.

Harvest, however, achieved over 100 million RMB in corn sales within just a few months of launching. This success was largely driven by the brand’s years of accumulated credibility and high consumer trust in the rice, grains, and beans categories, which translated swiftly into the new corn category.

From 2019 to 2022, Harvest ranked No. 1 in rice, grains, and beans sales across major e-commerce platforms. According to Frost & Sullivan, Harvest held a 14.2% market share in 2022, 2.7 times that of the second-ranked competitor.

An industry survey also revealed that Harvest boasts a customer loyalty rate of 60%. On e-commerce platforms, it’s common to see the same user ID placing multiple orders to different addresses, indicating that loyal customers not only buy for themselves but also gift products to family and friends.

In fact, in today’s sluggish consumption environment, even highly innovative products find it difficult to survive in "blue ocean" markets. For basic categories like rice and corn, where the "red ocean" of competition is already crowded with giants, breaking through is even harder.

Yet Harvest has consistently stood out, crossing from rice to corn, achieving breakthrough after breakthrough. How did they do it?

Beyond upstream factory construction, midstream warehousing, and relentless improvements in product quality, processing, and delivery efficiency, Harvest never neglected the essential question: How do we sell the product? Instead, it positioned itself not just as an agricultural brand, but as an Internet + Consumer + Agriculture company.

Facing a national consumer market, Harvest follows the HBG Theory—using an all-channel penetration strategy to enhance brand awareness and purchasing convenience.

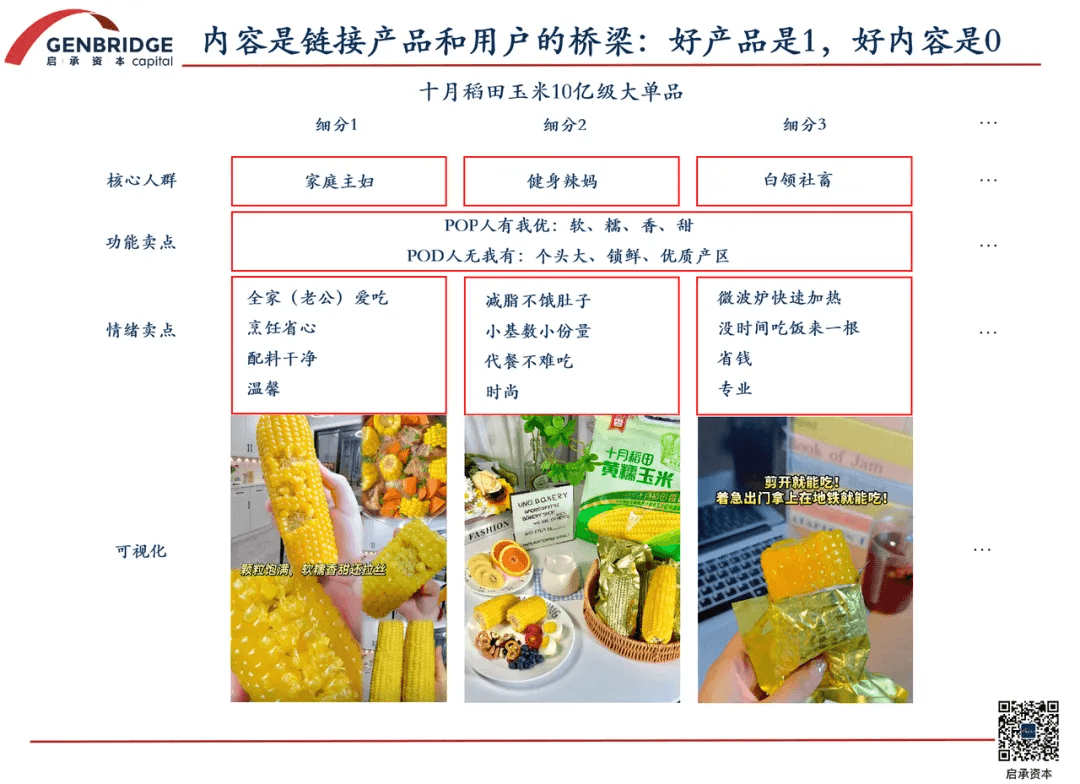

Specifically, a great product must aim to become the top-selling item in operations, ensuring it is the first brand that comes to mind. It must maintain real-time brand exposure across platforms like Tik Tok (TikTok China), Xiaohongshu (RED), Weibo, and WeChat, creating a strong network effect and ensuring constant visibility. At the same time, they must establish a comprehensive omnichannel presence, reaching consumers directly and ensuring efficient fulfillment, so that consumers can buy the product anytime, anywhere.

Online, Harvest conducts real-time brand promotion across Tik Tok, Xiaohongshu, WeChat, and Weibo, collaborating with prominent KOLs (Key Opinion Leaders) and KOCs (Key Opinion Consumers). On Tik Tok alone, the brand sees 30,000 short videos generated daily, with peak exposure reaching up to 30 million impressions.

For Harvest, content serves as the bridge connecting products and consumers. A good product is the "1," and good content is the "0" that follows—content acts as a multiplier, maximizing the influence and penetration of great products.

Offline, Harvest launched TV commercials for its corn products at airports, subway stations, and through elevator media. The brand’s founder personally endorsed the corn products, with the catchy slogan "Harvest! Fragrant, Fragrant, Fragrant" and mouthwatering footage of soft, stringy corn featured across multiple consumption scenarios. This high-frequency dual exposure of both the brand and the product category enabled consumers to recognize the brand within just three seconds.

Today, Harvest has established a strong presence across the top 10 e-commerce platforms, and the brand momentum accumulated online is now fueling its expansion into offline markets.

As Bing Wang, Harvest’s co-founder, explained, because the brand already enjoys significant consumer awareness and strong channel leverage, the cost of entering new sales channels is actually lower than that of many competitors. "We’ve built strong brand equity," he said, "which naturally gives us a powerful voice in the market. Combined with the advantages of our product offerings, more and more channel partners are now proactively approaching us for collaboration."

Redefining agricultural products

Harvest’s success in turning corn into a nationwide best-selling brand offers a new blueprint for the branding of agricultural products in China.

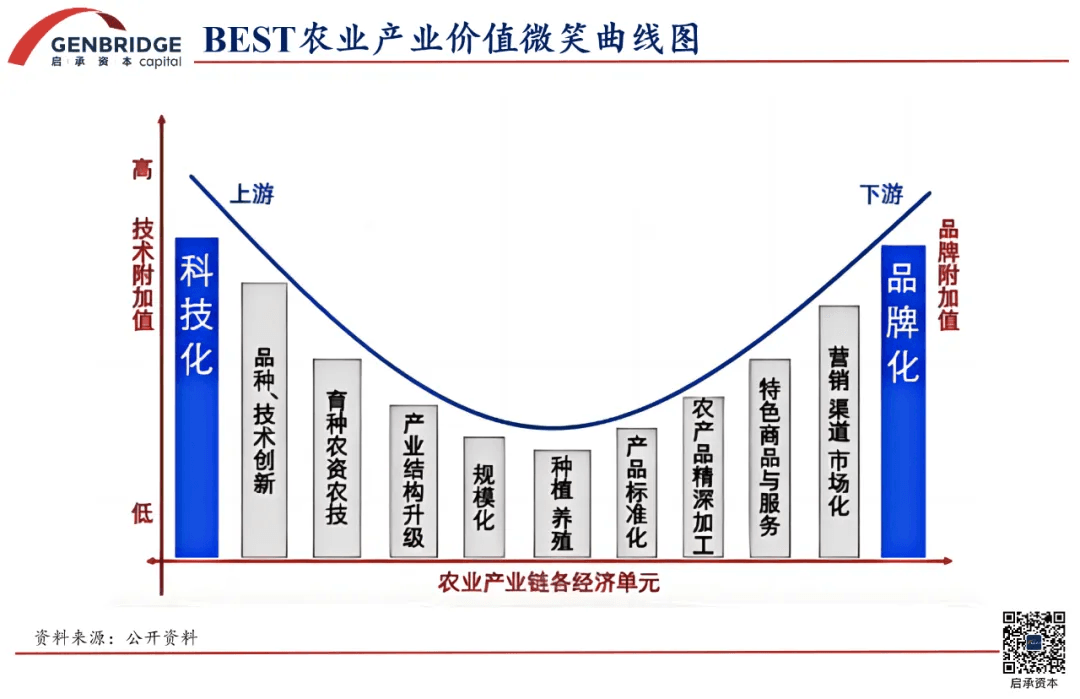

In the "smile curve" of agriculture, the upstream (technology and breeding) and downstream (retail and branding) ends typically enjoy the highest profit margins. Countries with advanced technologies and mature markets sit at these profitable ends of the agricultural value chain, while China’s agricultural sector still shows a "short, narrow, and thin" value chain, sitting at the bottom of the curve.

Thus, to escape the low-profit dilemma and achieve higher margins, Chinese agriculture must either move upstream to master technological capabilities or move downstream to build direct connections with consumers.

At the current stage of development, investing heavily in upstream R&D is a long and difficult journey.

In contrast, transforming the downstream—redefining how products reach consumers—is a more practical and achievable path.

Traditionally, agricultural products traveled through a long supply chain before reaching urban consumers:

Procurement agents collected crops directly from farmers, transported them to the cities, sold them to local distributors, who then sorted, repackaged, and wholesaled the products to supermarket buyers or market stall owners, who finally placed them on the shelves for sale.

Before Harvest, despite corn’s massive consumer base, there had yet to emerge a truly national corn brand.

The fundamental reason lies in the traditional model: corn sales were primarily a to B business—selling crops to distributors after harvest, without directly engaging with end consumers. Harvest broke this mold by fully integrating both online and offline channels, boldly and proactively presenting itself directly to consumers.

Moreover, the traditional supply chain model also suffers from poor communication between production and sales. Changes in consumer demand often fail to reach the supply side accurately and promptly.

Adding to this challenge is the long agricultural cycle—northeastern corn, for example, is harvested only once a year—which frequently leads to supply-demand mismatches and market imbalances.

All these factors have contributed to the predicament of northeastern corn: large production but small markets. Domestically, corn has traditionally followed a "north-to-south" distribution pattern, but due to long transportation times and outdated storage conditions, southern consumers often received corn that lacked freshness compared to its original quality in the north.

Bing Wang and Wenjun Zhao, founders of Harvest, experienced these issues firsthand.

In the early stages of their entrepreneurial journey, they started with the traditional agricultural wholesale business, slowly building up their understanding of the grain industry and the circulation chain.

They later recalled that during their early years in Northeast China, making a profit was nearly impossible—there were too many players in the grain business, intense homogenization, and a lack of recognizable brands.

To break out of this fierce competition, they decided that when they shifted operations from Northeast China to Beijing, their top priority would be building a brand. Around 2010, noticing that "products could now be sold 24/7 on e-commerce platforms," Wang and Zhao realized this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity: they could bypass layers of offline intermediaries and use online platforms to directly establish their brand.

As a result, Harvest’s first blockbuster product on JD quickly accumulated 5–6 million reviews, with a 99% positive rating. Later, consumers first came to trust the Harvest brand, which then drove the company’s expansion into foodservice, industrial supply, and distribution networks.

Today, after years of dominating the top spot in the rice category, Harvest is once again making a major impact—this time in the corn market—by leveraging its accumulated advantages in supply chain management and brand reputation.

At this point, Harvest has not only achieved unprecedented success but also provided the entire industry with a new solution: starting from building agricultural brands, constructing a new type of industry chain, and thereby shaping the systemic influence of modern agriculture.

In this regard, Zespri and New Zealand's kiwifruit industry offer an excellent example.

Over 120 years ago, kiwifruit seeds from China were brought to New Zealand. Initially, a group of small farmers independently grew and sold kiwifruit. After the local market became saturated, they began exporting globally. From the 1950s to the 1970s, New Zealand almost monopolized the global kiwifruit market.

However, because production was highly fragmented, product quality was inconsistent, and farmers engaged in destructive price competition, there was no unified branding for New Zealand kiwifruit.

Soon, other countries entered the kiwifruit market, and New Zealand lost its global leadership, eventually being overtaken by Italy.

To reclaim their advantage, over 2,700 New Zealand kiwifruit growers agreed to dissolve their individual brands and joined the government-supported New Zealand Kiwifruit Marketing Board, integrating all export channels under one system and creating a unified industry strategy.

In 1997, the New Zealand government restructured the Marketing Board into two entities: one, Zespri, responsible for global brand marketing and product export; the other, responsible for upstream supply chain management and variety development. Thus, the kiwifruit industry shifted from a fragmented farm-to-market model to a corporatized operation, concentrating resources on building the Zespri brand.

After decades of development, Zespri now sells approximately 17.3 billion RMB (around USD 2.4 billion) worth of kiwifruit annually, commanding about one-third of the global market.

This brand story, once played out in the Southern Hemisphere, is now being echoed on the black soil plains of Northeast China. From rice to corn, Harvest is pioneering a new path for the branding and upgrading of Chinese agricultural products.