Darden’s Secret to be a Unique "Against-the-Trend" Player

In today’s Chinese restaurant market, discussions about “growth slowdown” and “intensifying competition” have been constantly emerging. Restaurant companies are searching for new avenues of growth and expansion, yet most efforts yield little success.

However, in North America, one company stands as an exception—Darden Restaurants.

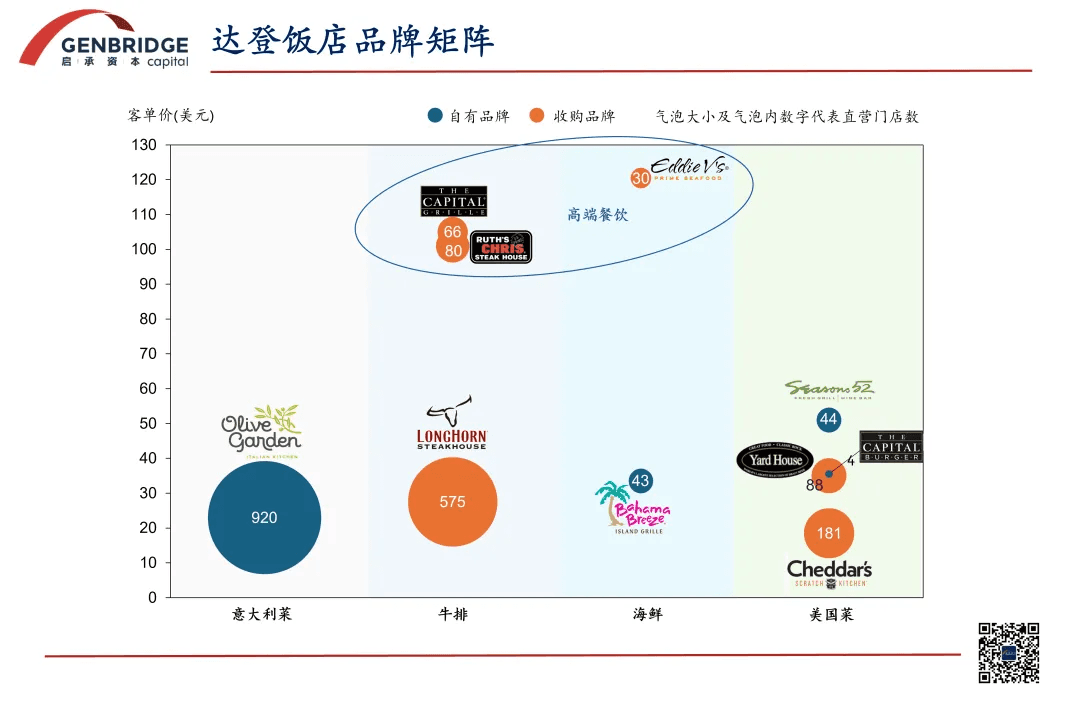

Darden Restaurants Group owns ten dining brands spanning various cuisines, including Italian, seafood, steak, upscale Western dining, and Mexican cuisine. These brands focus on casual full-service dining and are known for their differentiated menus, friendly service, and comfortable ambiance, with an average customer spend of around $30.

Beyond these, Darden also operates high-end restaurant brands such as Ruth’s Chris, Eddie V’s, and The Capital Grille, where the average customer spend exceeds $100.

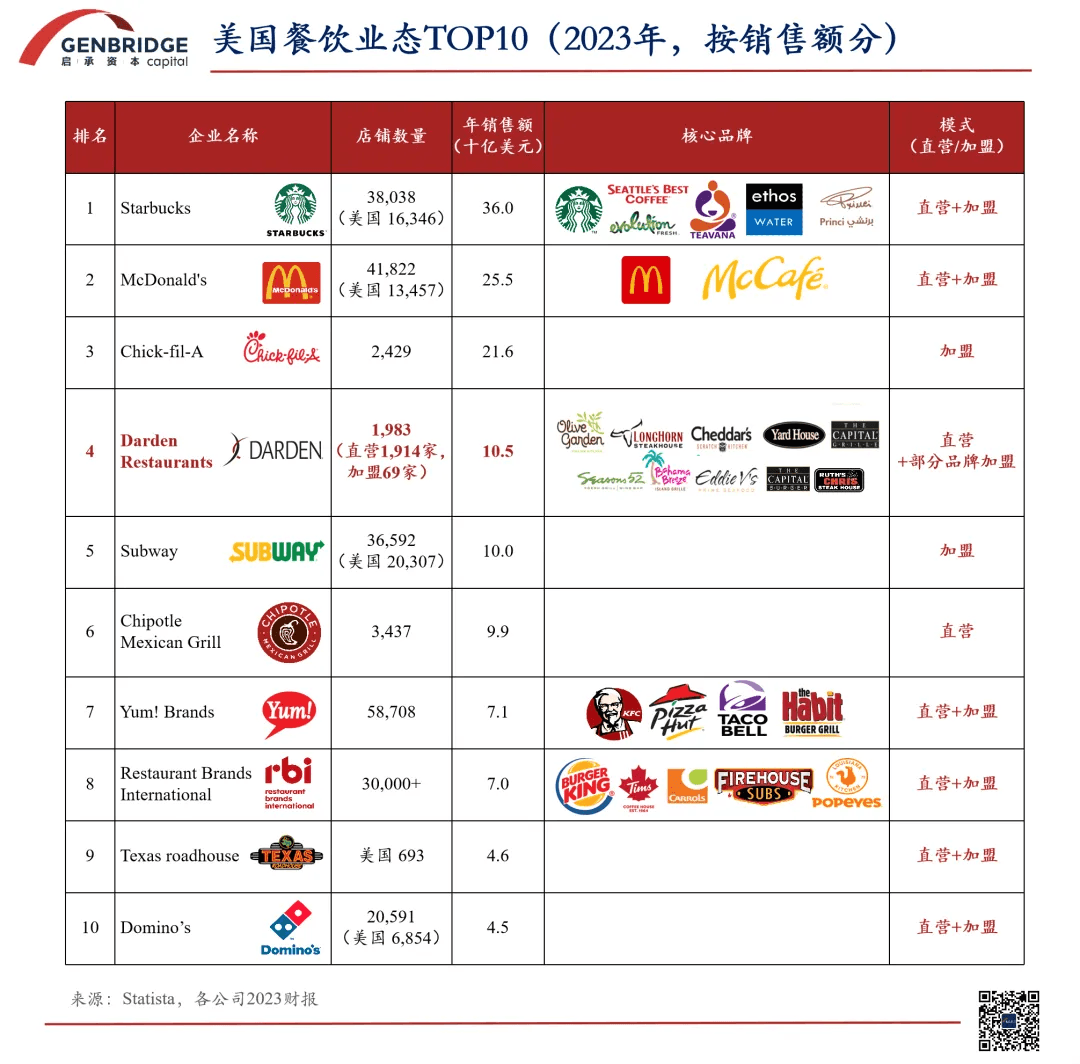

It is well known that in the U.S., standardized restaurant chains like McDonald’s and Subway, which primarily operate through franchising, dominate the market. In contrast, Darden is a multi-brand group focused on full-service casual dining. Despite having only around 2,000 locations—most of which are directly operated—it has firmly secured its place among the top 10 restaurant brands in the U.S.

The past 20 years have been challenging for the full-service dining industry in America. The rise of millennial consumers reshaped dining preferences, standardized fast food chains gained market share, digital platforms disrupted traditional restaurant models, and the financial crisis led to a decline in the middle class. Many well-known restaurants were forced to shut down.

This article will break down the secrets behind Darden’s growth from the following perspectives, hoping that its experience can offer valuable insights for Chinese restaurant businesses:

- The rise of Darden and its resonance with the times

- How has Darden managed to thrive across economic cycles?

- The keys to building a successful multi-brand portfolio

- How can Chinese restaurants break free from the low-price competition trap?

The rise of Darden, resonating with the era

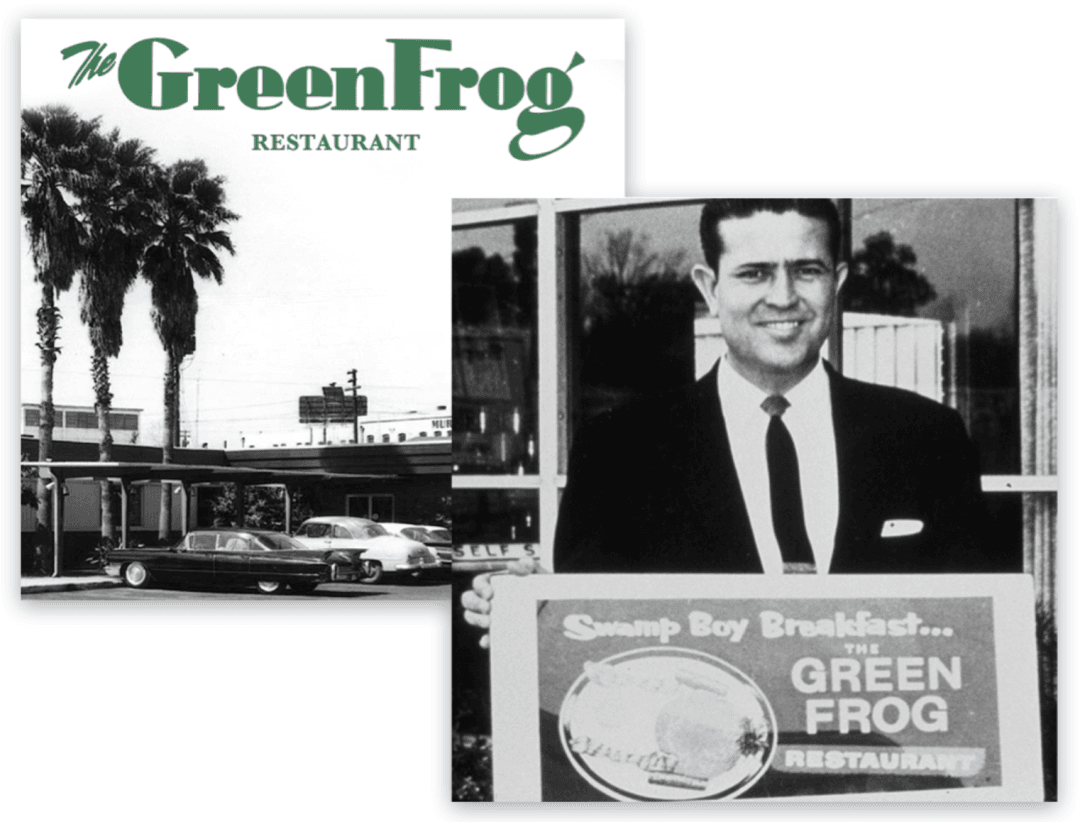

The history of Darden Restaurants can be traced back to 1938. At that time, Bill Darden, only 19 years old, set up a lunch counter named "The Green Frog" in Georgia. In an era when fast food was not yet widespread, The Green Frog defied Southern laws by refusing to segregate customers based on race, which led to its tremendous success.

With the success of The Green Frog, Darden began investing in restaurants and hotels in Florida. This move coincided with the rise of the middle class in the American South and the growing trend of dining out.

Over the first thirty years of his entrepreneurial journey, Bill Darden learned at least two crucial lessons: 1) High-quality service is essential for a restaurant's success; and 2) Observing consumer needs and striving to meet them.

For instance, Darden noticed that seafood was the best-selling item in his restaurants. Consequently, in 1968, he opened the first "Red Lobster" restaurant, specializing in seafood, in an inland area far from the coast. With a more extensive menu and more affordable prices, the first Red Lobster caused a sensation upon its opening: every parking spot was filled, and customers lined up just to taste the fresh lobster shipped from the coast.

The sudden rise of Red Lobster caught the attention of major corporations. In 1970, General Mills acquired Red Lobster under favorable terms. A decade later, Red Lobster's annual sales had reached nearly $400 million, and by 1985, the number of locations had expanded from the initial 3 to nearly 400.

Witnessing the noticeable growth of Red Lobster, General Mills began experimenting with multiple brands. In 1982, to capitalize on the popularity of Italian cuisine, General Mills founded Olive Garden, an Italian-themed restaurant, with the slogan "Good Times, Great Salad, Olive Garden."

From the outset, Olive Garden distinguished itself with unlimited salad and breadsticks. By 2009, Olive Garden had served 612 million breadsticks and 165 million bowls of family-style salad—enough for every American to have two breadsticks and half a bowl of salad.

Olive Garden was also the first full-service Italian restaurant to offer unlimited pasta, where customers could enjoy a variety of pastas and sauces for $8.95. Olive Garden aimed to provide quality dining experiences for families, catering to all age groups, and even created a special children's menu [1].

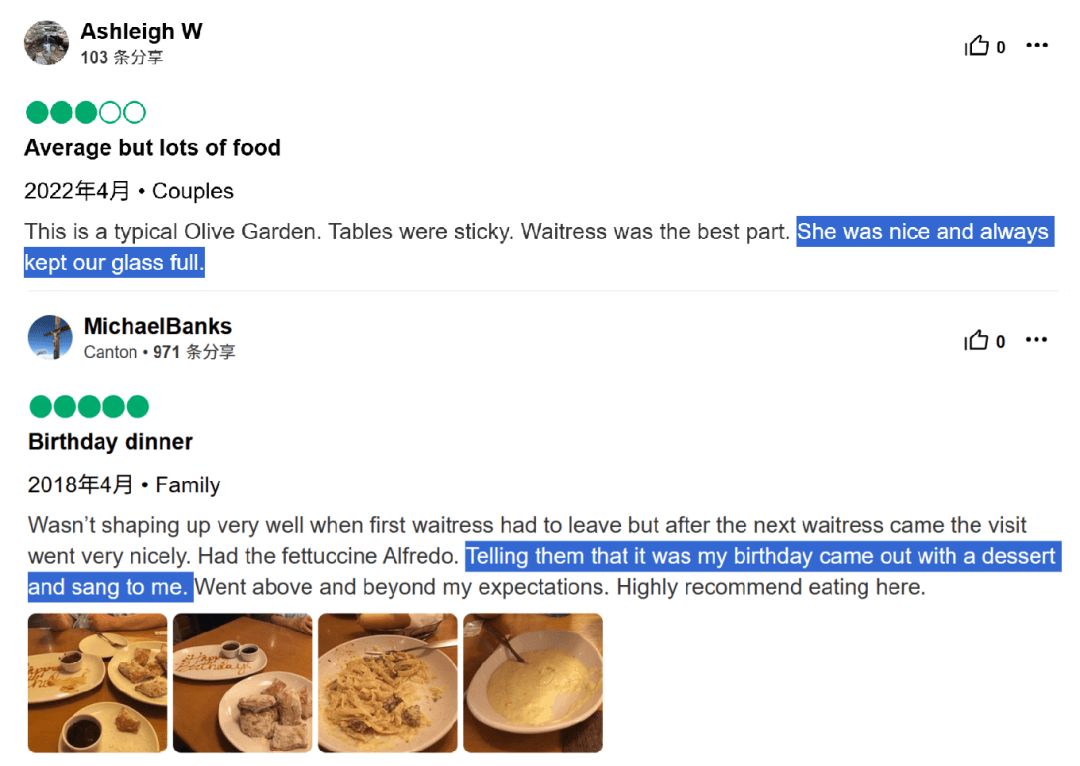

The marketing strategy centered around free offerings and differentiated services laid the foundation for Olive Garden to surpass its competitors in the restaurant industry, earning it the reputation of being the "American Haidilao " for the local people.

In reviews of Olive Garden, it’s common to see praise for servers promptly refilling drinks, offering free breadsticks while waiting for a table, and even presenting a dessert and singing for customers on their birthdays [1]. Taylor Swift even mentioned Olive Garden in her song—"Este wasn't there Tuesday night at Olive Garden"—prompting Olive Garden's CEO to personally thank her during an investor conference call.

By 1989, Olive Garden had expanded to 145 locations, becoming the fastest-growing division within General Mills' restaurant portfolio. By 1993, Olive Garden had over 400 locations, solidifying its status as a household name [2].

However, good times didn’t last long. General Mills suffered a significant setback when attempting to venture into the Chinese restaurant chain business, incurring losses of nearly $20 million. To mitigate these losses and refocus on its food brands, General Mills packaged Red Lobster and Olive Garden into Darden Restaurants and spun it off as a separate entity.

In May 1995, Darden Restaurants went public on the New York Stock Exchange. Thanks to the spin-off, General Mills' restaurant division achieved a net income of $108 million that year.

At the time, the U.S. stock market experienced a wave of restaurant IPOs: Starbucks went public in 1992, and in 1997, Yum! Brands spun off from PepsiCo, taking KFC, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and other brands public.

To reinforce its position as a beloved family-friendly restaurant, Olive Garden launched its iconic slogan in 1998: "When you’re here, you’re family". This phrase not only resonated deeply with diners but also became one of the most recognizable advertising taglines in America [2].

This "American-style Haidilao" grew rapidly, achieving 50 consecutive quarters of same-store sales growth, laying a solid foundation for its parent company, Darden Restaurants, to pursue future acquisitions.

Survivors in the age of standardization

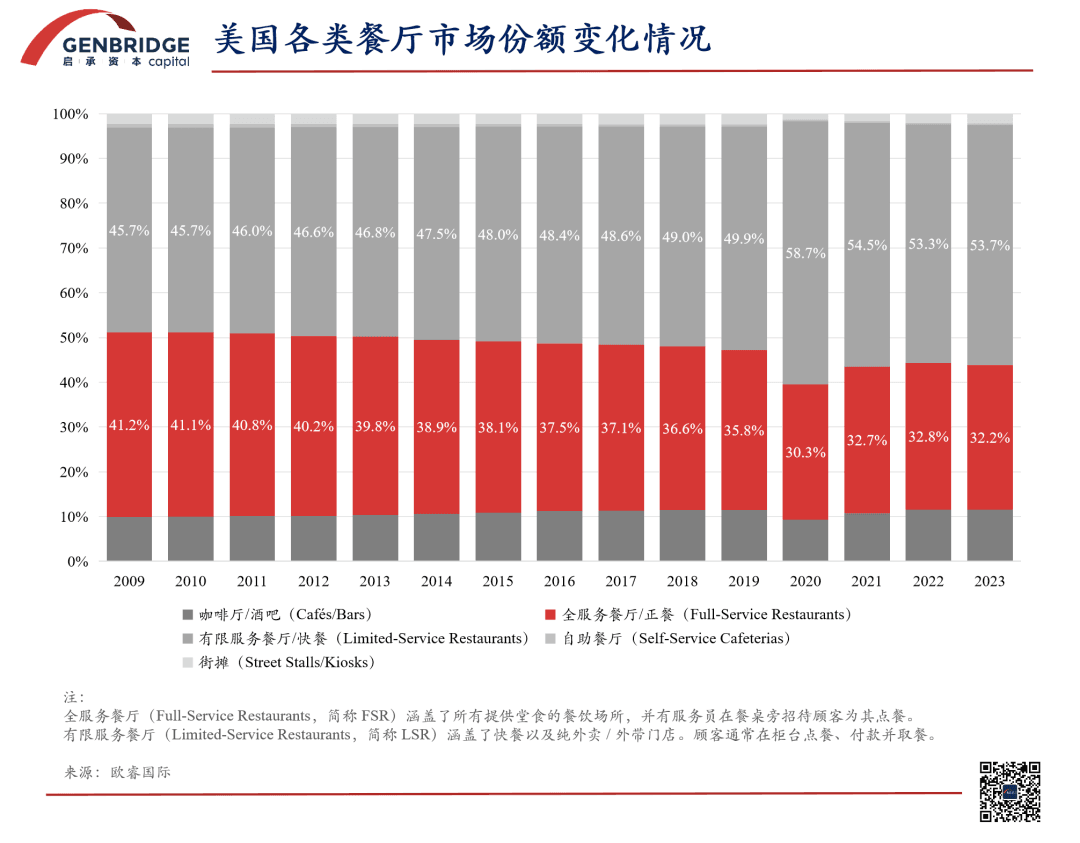

From the perspective of the U.S. restaurant industry structure, Red Lobster and Olive Garden, both under the Darden Group, are "full-service" restaurants. These types of restaurants tend to emphasize service and are primarily operated through direct ownership, with significant regional flavor and style variations, making them almost the antithesis of efficiency.

Another category includes limited-service restaurants, which are more standardized and typically expand through a mix of direct ownership and franchising, with a lighter asset structure. McDonald's, Burger King, and KFC are under this category.

As the U.S. restaurant industry entered the 21st century, consumer habits began to evolve. Limited-service restaurants, with their simplified menus, unique concepts, speed, and convenience, have been rapidly capturing market share from full-service restaurants. Darden has also faced a crisis.

The rapidly expanding limited-service restaurants are usually single-brand operations, meeting key characteristics for the market: large market potential, high standardization, and broadly appealing flavors. By tapping into the shifting tastes of the millennial generation, these brands have seen rapid growth in market share.

For example, Chipotle, founded in 1993, focuses on Mexican cuisine segment and aligns with consumers' increasing demand for healthy fast food. Since IPO, its revenue has grown at a compound annual growth rate of 15.8%, far outpacing competitors. (Recommended Reading: Chipotle: Creating a $10 Billion Value with "Fresh Customization" | GenBridge Researchhttps://www.genbridgecapital.com/news/id/chipotle-billion-dollar-value-through-fresh-customization)

Chipotle boasts a nearly perfect store model: through a clever combination of product structures, it offers consumers over 100 customizable options, yet only requires more than 50 types of raw materials. Additionally, its assembly-line-style food preparation and delivery system supports the store's meticulous and highly efficient operations.

Since its IPO in 2006, Chipotle’s market value has increased by more than 60 times. Today, its market value stands at $85.462 billion, making it the third-largest publicly traded restaurant company globally, after McDonald's and Starbucks.

While fast-food chains achieved explosive growth through standardized store models, rapidly capturing markets across the U.S., Darden Group—focused on full-service dining—faced challenges in scaling quickly due to constraints like regional taste preferences and operational complexities.

The founders and later management of Darden understood the market ceiling for a single brand and business model inherently limits growth potential and exposes the company to systemic risks.

To diversify, Darden began testing new restaurant concepts such as Bahama Breeze, Smokey Bones BBQ, and Seasons 52. However, by 2007, these efforts stalled as the broader dining market slumped, and the new brands underperformed.

Rather than building brands from scratch, Darden pivoted to acquisitions.

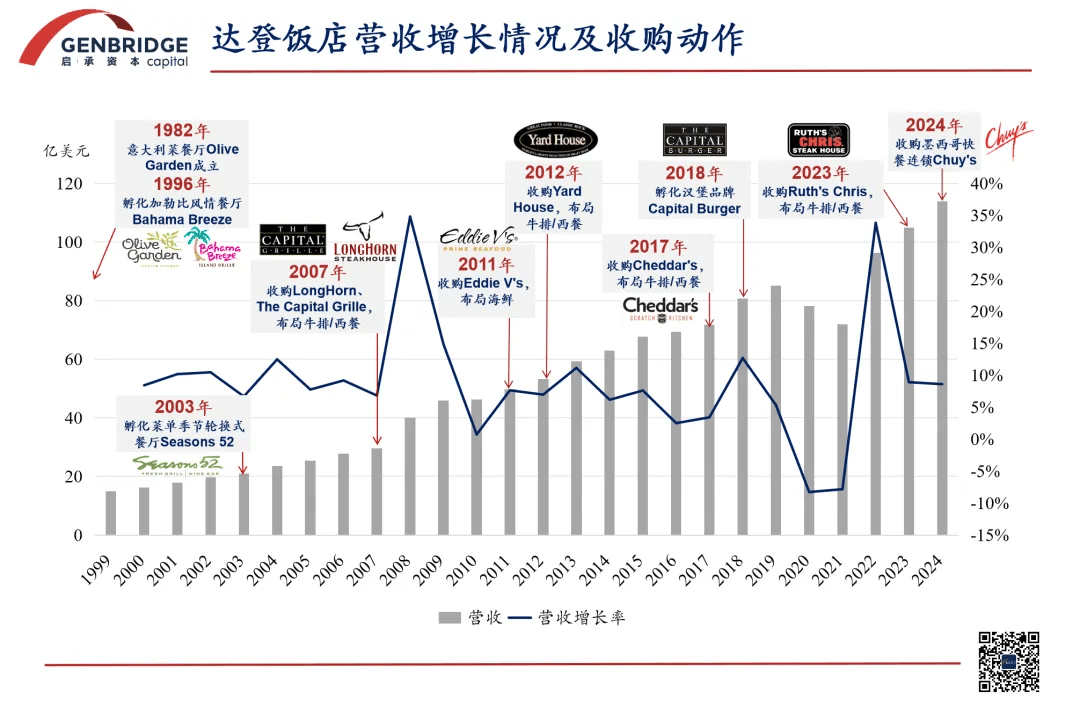

In August 2007, Darden spent $1.4 billion to acquire Rare Hospitality, a competitor based in Atlanta, gaining control of two of Rare's chains—The Capital Grille and LongHorn Steakhouse.This marked Darden’s first successful large-scale acquisition since going public [3].

From the time of the acquisition in 2007 until the end of 2008, LongHorn's total sales reached $575 million, a 7% increase from the previous year, setting annual revenue records. Today, LongHorn has become Darden’s second-largest brand, just behind Olive Garden, with 575 locations and annual sales of $2.8 billion.

Darden now owns 10 restaurant brands—6 acquired and 4 homegrown—spanning low, mid, and high price points. These brands vary in design, regional focus, and culinary styles, enabling the company to cater to diverse customer demographics, geographies, and taste preferences.

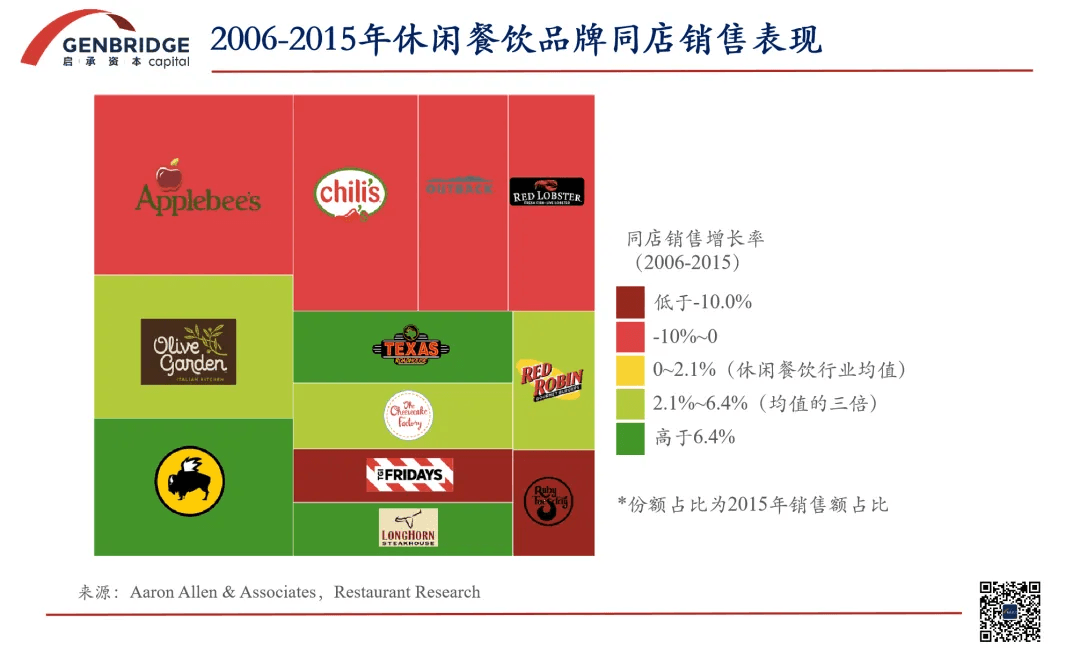

Even during the decade from 2007 to 2017, when the casual dining sector saw no growth [4], Darden refused to compromise on pricing or downsize its restaurants. Instead, it doubled down on differentiated service, achieving growth against industry headwinds.

Over the past two decades, Darden’s revenue has nearly tripled, its store count has grown from 1,250 at its IPO to 2,031 in FY2024, and its stock price has soared by tens of times.

The secret to thriving through economic cycles

If Chipotle represents an efficiency-driven fast-food model, Darden’s brands take a value-driven approach, focusing on service and unique customer experiences.

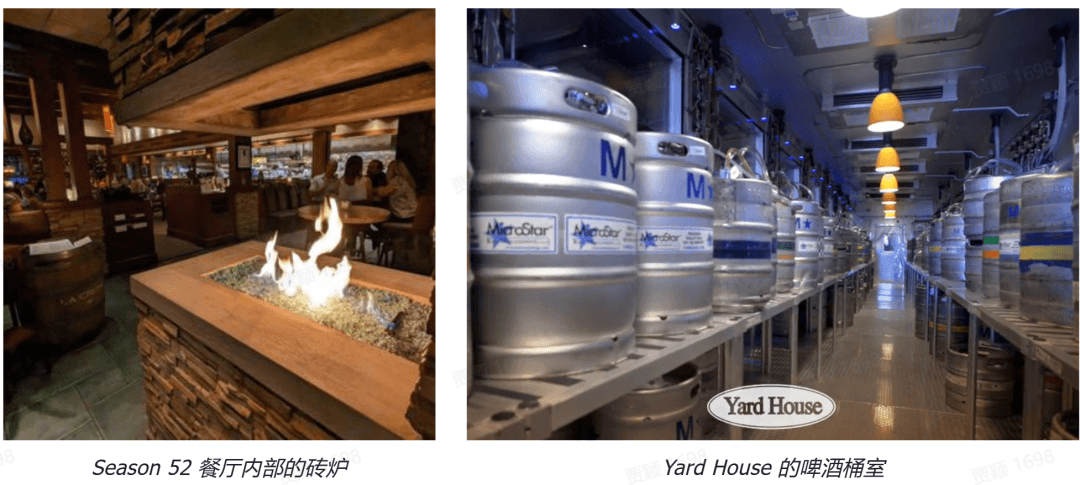

For example, LongHorn Steakhouse insists on using only fresh steaks, never frozen. Seasons 52 enhances natural flavors with traditional cooking techniques like oak-fire grilling and brick ovens. Yard House offers a customized beer menu at each location, with dedicated keg rooms storing up to 5,000 gallons of beer and an average selection of over 100 varieties per restaurant.

Managing a diverse, large-scale restaurant group like Darden is no easy task. To maintain efficiency, Darden has upgraded its supply chain and implemented a digital restaurant network, positioning itself as the "Walmart of the restaurant industry".

Unlike franchise-based restaurant chains, Darden operates all its locations directly and has built its own procurement and warehousing system. This strategy enabled Darden to launch a supply chain upgrade in 2010.

By 2012, Darden had developed its "I Kitchen" network software system, which tracks all shipments from warehouses to restaurants using GS1 barcodes. This allows full traceability of inventory, optimizes stock usage, and improves demand forecasting.

The system also enables real-time collaboration with suppliers and logistics partners, increasing efficiency while reducing procurement and storage costs.

Darden estimates that once fully implemented, this system will save $45 million annually on food supply chain costs—roughly equivalent to the food procurement budget for 35.8 Darden restaurants at that time. As more brands join the group, these supply chain synergies will become even more significant.

This synergy also helps Darden offset rising food costs. While the U.S. food CPI has been growing at 2.5%–5% annually, Darden’s menu prices have only increased by about 2% per year, demonstrating its ability to absorb cost pressures.

By leveraging a strong brand portfolio on the front end and an efficient supply chain on the back end, Darden has built the flexibility to navigate economic downturns and shifting market trends.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the shrinking middle class—Darden’s core customer base—led to tighter consumer spending. In response, Darden strategically divested its struggling seafood chain, Red Lobster, in 2014, refocusing on Olive Garden and LongHorn Steakhouse. Through operational improvements, same-store sales growth gradually stabilized, reinforcing Darden’s long-term resilience.

Faced with changing consumer habits and economic fluctuations, multi-brand restaurant groups like Darden are better equipped to withstand systemic risks.

In 2023, while the casual dining sector underperformed compared to fast food, Darden defied the trend with its diversified brand portfolio. Olive Garden maintained its dominance as the king of casual dining with an 8.8% sales increase, while its sister brands LongHorn Steakhouse grew by 10.2%, Yard House by 12.6%, and Cheddar's Scratch Kitchen by 9.1%.[5]

Looking at Japan’s experience, major restaurant brands have tacitly adopted multi-brand strategies to navigate the challenges of a saturated market era.

In the early 1990s, Japan’s economic growth stagnated, compounded by declining birth rates and an aging population, leading to a 30-year period of market saturation and intensifying competition in the restaurant industry.

In this highly competitive environment, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) became a key growth strategy:

Zensho Group successfully listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 1999, securing a financial foundation to acquire various restaurant companies.

Over the years, Zensho acquired COCO’s (a listed restaurant chain), Nakau (Japanese fast food and beef bowls), and Takarajima (casual dining and budget-friendly BBQ) while simultaneously building a nationwide supply chain and backend support system, laying the groundwork for its Mass Merchandising (MMD) model.

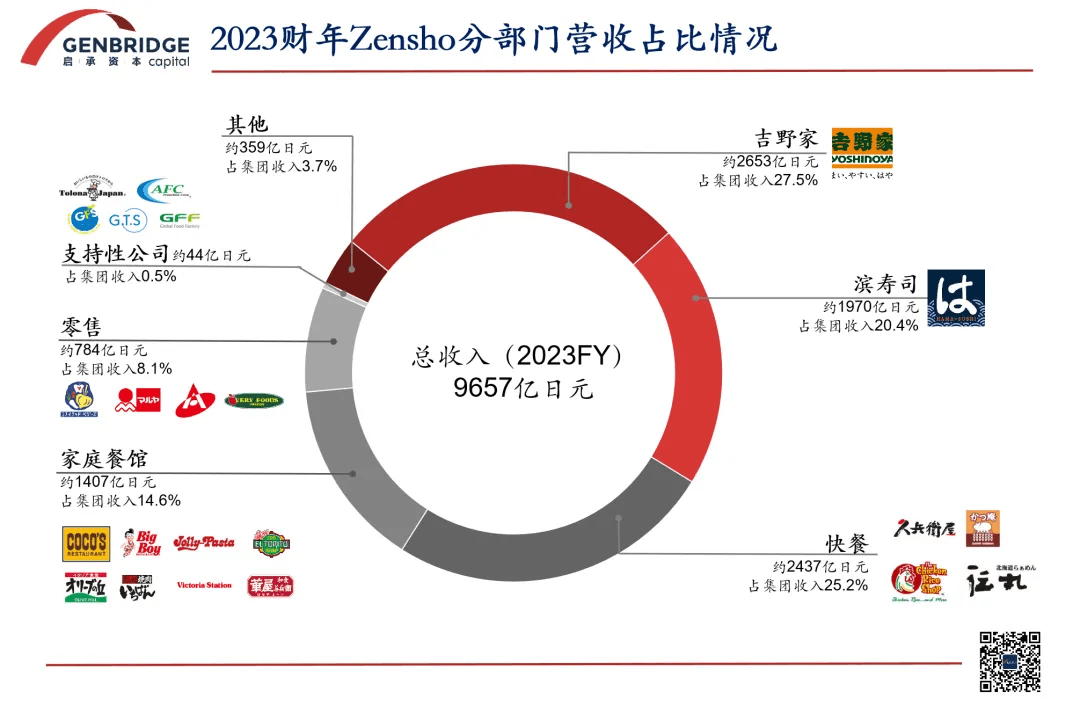

Today, Zensho Group owns over 30 restaurant brands spanning four major sectors: fast food, sushi, Western-style family dining, and retail.

Thanks to its highly efficient organization and diversified brand portfolio, Zensho has continued to expand even in a declining market. It now operates 15,109 locations with annual revenue reaching 965.7 billion yen (approximately 46.8 billion RMB)—making it the undisputed leader in Japan’s restaurant industry, nearly 2.5 times the size of McDonald's Japan.

Chinese dining trapped in intensifying competition

From the experiences of the U.S. and Japan, building a multi-brand portfolio seems like the go-to strategy for restaurant groups, but in China, failures are far more common than successes.

As competition in China’s restaurant industry has intensified in recent years, many brands have turned to launching sub-brands as a survival strategy:

Jiu Mao Jiu incubated Tai Er and Song Chongqing Hotpot Factory. Xiabuxiabu launched ChaMiCha, CouCou, and ChenShou (a BBQ + alcohol + tea concept). Yang Guofu introduced Ma La Ma La for spicy hotpot-style noodles. Other major players like Xibei, Haidilao, and Banu Hotpot have also been actively developing sub-brands.

However, running sub-brands is no easy task. Haidilao launched 10 sub-brands in 2020, only for most to fade into obscurity. Even Yum China, which successfully acquired KFC, Pizza Hut, and Taco Bell overseas, has struggled with acquisitions and brand expansion in China:

In 2005, Yum China launched its first Chinese fast-food brand, East Dawning, but it failed to gain traction and was quietly phased out by 2021.

In 2009, Yum China privatized Little Sheep, then the newly listed “first hotpot stock” in China. However, instead of expanding further, Little Sheep shrunk dramatically—its store count plummeting from a peak of over 700 locations to just 122 today.

So why have multi-brand restaurant groups thrived in the U.S. and Japan, while Chinese companies struggle?

The core issue lies in the extreme diversity and regional variations of Chinese cuisine, which make standardization significantly more difficult—a major bottleneck for the industry’s development.

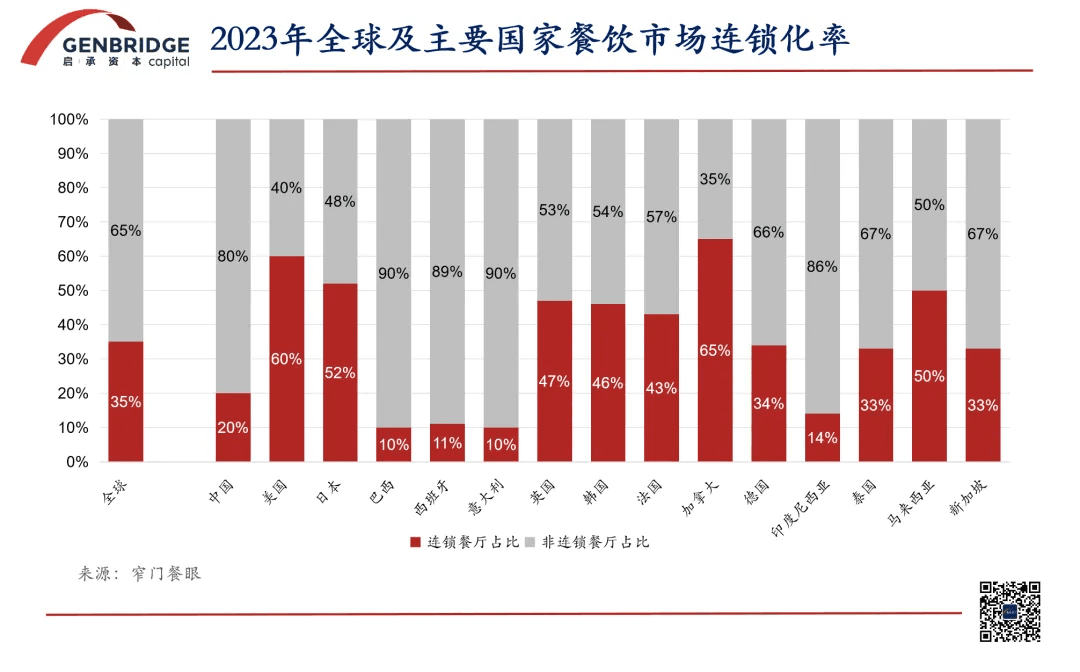

As a result, China’s restaurant market remains highly fragmented, making large-scale, standardized operations difficult. China’s restaurant chain penetration rate is only 20%, just one-third of the U.S.. Even within Asia, China lags behind Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand in terms of restaurant chain adoption.

Secondly, China’s restaurant supply has severely outpaced demand, leading to intense competition. According to Hongcan.com, the total number of restaurant locations nationwide has surpassed 9 million. Data from Jihai further reveals that China’s per capita restaurant availability is more than three times that of the U.S.

At the same time, consumer spending willingness is gradually declining. Meituan disclosed at the 2024 Restaurant Industry Conference that compared to 2023: same-store sales are decreasing, high-tier cities are experiencing a downturn, aerage transaction values are falling.

Looking at the development trajectory of the U.S. restaurant industry and Darden’s experience, we can see that while economic fluctuations present major challenges, they do not mean a dead end for the industry.

One critical takeaway: blindly slashing prices is not the solution. Instead of obsessing over price cuts, restaurant brands should focus on understanding evolving consumer preferences and enhancing their service and experience offerings.

Despite the overall industry struggling, new brands continue to emerge, quickly rising to prominence by leveraging differentiated services. Many have become the new traffic-driving forces in major shopping centers across top-tier cities.

As some brands rise, others inevitably fade. A constant influx of viral restaurants is rapidly displacing established players, while trends are shifting faster than ever—from pickled fish to coconut chicken to sour soup hotpot, the cycle of popularity is accelerating.

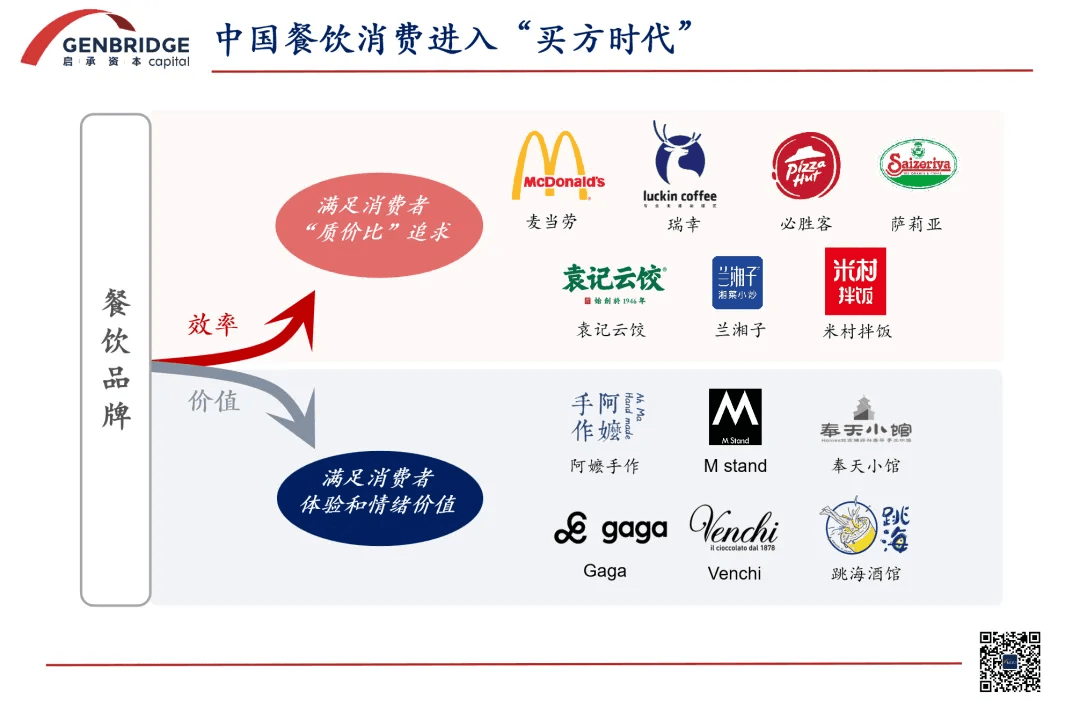

With consumer preferences diversifying at an unprecedented pace, China’s restaurant industry is now fully entering a new “buyer’s market” era.

We have observed that restaurant brands are gradually splitting into two distinct camps:

- Efficiency-driven brands, catering to consumers’ demand for “value-for-money”. Brands like McDonald’s, Luckin Coffee, and Micun Bibimbap fall into this category, with steadily rising performance.

- Value-driven brands, focusing on differentiated experiences and emotional appeal. This includes handcrafted milk tea, small bars, and Italian gelato, which have become particularly popular among young consumers.

In an industry marked by rapid change and fierce competition, trends are fleeting, and market directions are unpredictable. However, the fundamental survival principles for restaurant brands remain timeless and effective: find the right positioning, safeguard cash flow, never compromise on food quality and service.

References

[1] Olive Garden Italian Restaurant, Tripadvisor

[2] The Journey of Olive Garden: From Start-up Success to Iconic Italian Chain, Nextloc

[3] Darden to buy RARE steakhouse chains, Reuters

[4] Casual Dining Restaurant Chains Entering Dangerous Waters, Aaron Allen & Associates

[5] Casual-dining chains had a difficult year, Restaurant Business