In 2020, Don Quijote (Group Name: Pan-Pacific International Holdings), with 800 stores and a revenue of 1.6819 trillion yen (approximately 100 billion RMB), became the fourth-largest retail enterprise in Japan.

Diverging from the discount models of Costco, Aldi, Walmart, and others in Europe and the United States, which achieve price advantages through reducing SKUs and lowering operational costs, Don Quijote adopts a model characterized by wholly-owned operations, stores exceeding 3,000 square meters, intensive display of over 10,000 SKUs, and a mixed sales strategy of 30% low-priced clearance items and 70% regular price discounts. This approach provides consumers with an impression of abundant and affordable choices.

The success of the Don Quijote model is attributed to its alignment with the unique characteristics of Japanese retail distribution. This article will delve into the macro perspective of the Japanese retail landscape and try to decode the winning strategies of the discount store industry in Japan.

- What structural environmental changes led to the emergence of Don Quijote?

- Why did other discount stores of the same era fail?

What structural environmental changes led to the emergence of Don Quijote?

Established on the eve of the burst of the economic bubble in 1989, Don Quijote’s success can be attributed to a strategic alignment with post-economic bubble Japan, where macroeconomic downturns and a heightened consumer price sensitivity created a favorable environment. Don Quijote effectively capitalized on the transition from an era of incremental growth to a period characterized by existing market saturation. The key variables driving this shift were: a) the explosion of new product quantities, b) the surge in information availability and shortened life cycle of products, and c) the rise of convenience store channels.

Variable a: Explosion of New Product in a Saturated Market:

Commencing with the 1980s, often dubbed the era of the “bubble economy,” significant shifts occurred beneath the surface of the apparent economic prosperity. While housing and share prices, luxury items, imported cars, and high-end villas reached their peak, the average consumer’s spending power did not witness a substantial increase. From 1980 to 1989, real comsumption expenditure per household grew at about 2%, far less than the 4% to 5% in the last decade.

The reduction in economic dividends prompted consumer brands to expand product categories and intensify new product development to sustain revenue growth. For instance, in the late 1980s, Nissin Foods underwent organizational restructuring to expand its brand matrix, and elevate the speed of its value chain turnover, leading to a remarkable increase in the pace of introducing new products, from a modest four SKUs annually to an impressive 600 SKUs per year. This phenomenon mirrors the current proliferation of new product launches and brand strategies in China. To maintain growth, companies prioritized revenue over profit, abandoning profit margins.

Variable b: Information Explosion and Shortened Product Lifecycles:

The peak of consumer culture in the 1980s brought about an explosion of consumer information. Japanese scholar Yamazaki Kazu, in his work “The Birth of Soft Individualism – Aesthetics of Consumer Society,” delves into an analysis where he examines that modern consumers were not just consuming products but actively engaging in the consumption and production of information about these products. If the struggle between humanity and nature characterizes the second industry, then the third industry can be seen as the arena for interpersonal interactions. The retail industry’s focus has shifted from production and transportation to the essence of consumption itself, as reflected in the exponential rise of magazines, with the number increasing from 2,319 in the 1970s to 3,225 in the 1980s. In every niche, several magazines have proliferated, each featuring amateur KOLs producing consumer information from the perspective of the consumers.

By the 1990s, this trend intensified, accompanied by accelerated information dissemination due to the development of digital media platforms. The emergence of multimedia information platforms such as smartphones has accelerated information dissemination, significantly shortening product lifecycles, and creating a “boil-cool” phenomenon, where products went viral through a certain media channel and then quickly became unfrequented in a fortnight. Brands, eager to capitalize on trending products, often found themselves with excess inventory once the initial hype subsided.

As Marx mentioned in Critique of Political Economy, a product’s value is only validated when it is converted into currency, known as the “commodity’s precarious leap.” The normalization of the “boil-cool” phenomenon added a new level of complexity to this leap. The explosion and acceleration of information have resulted in a shortened product lifecycle, challenging both the front-end marketing strategies and back-end supply chain capabilities of brands.

Variable c: Rise of Convenience Store Channels – Fierce Competition for Limited Spaces:

The success of the convenience store model hinges on efficiency, with the output of each store location playing a crucial role. The number of convenience stores in Japan rose from 7,060 in 1987 to 29,144 in 1995, exerting a growing influence on the retail industry. To secure space in these stores, brands were compelled to continually introduce new products from various angles such as new materials, flavors, packaging, and processes, aiming to attract consumers and compete with channels. This competition led to the frequent appearance of “seasonal limited edition” products in Japan.

Convenience stores in Japan function as testing grounds for new products, and according to a former senior executive at Family Mart, only 3 out of 100 new products can survive beyond the first year. In the snack category, approximately 20 new SKUs are introduced each week. If sales fail to meet expectations, convenience stores will remove them from the shelves within 1-2 weeks, returning the remaining products to the brand or intermediary. In recent years, Japanese convenience stores have intensified the development of their respective Private Brands, focusing on R&D from the demand perspective to create products of higher quality than National Brands. This compels local Japanese brands not only to contend with competition among themselves but also to confront the high-margin Private Brands of the channels.

Answer to Question 1:

The three variables described above are intricately linked. In Japan’s market with a relatively low ceiling, consumer goods brands continually test new products to increase their revenue. On one hand, brands market themselves by introducing trendy new products to attract consumers. On the other hand, they actively compete with distribution channels to secure valuable shelf space in convenience stores. This characteristic of competition in a saturated market leads to a significant increase in the number of new product launches.

However, as mentioned earlier, out of 100 new products, only 3 manage to survive until the next year. It’s like a knight adorned in shining armor, triumphantly entering the city gates while stepping on countless bloody corpses beneath his feet.

So where do the rest 97 go?

Don Quijote is their outlet.

The more new products are introduced through mainstream channels, the more surplus inventory accumulates in society, and consequently the more supply in discount stores. Don Quijote was born based on the characteristics of the Japanese retail industry. It is the “shadow” of the retail industry in Japan. The brighter the sun shines, the larger the shadow.

Competitor Analysis: Why Did Contemporaneous Discount Store Fail?

From across the Pacific, observing the success of American discount store enterprises like Kmart, Walmart, and Costco, the Japanese retail industry has shown a keen interest in the discount store format since the 1980s. Various companies actively explored to create a Japanese version of a star discount store.

These enterprises can be broadly categorized into two models: hard discount and soft discount.

- Hard discount is similar to the American discount store model, reducing SKUs and operational costs, establishing vertical supply chains, launching Private Brands to lower retail prices through channels.

- Soft discount achieves ultra-low prices by selling surplus, clearance items, and financially mortgaged products, citing product shortages to attract the initial customer base.

Competitors in the Hard Discount Model: Daiei, Walmart, Carrefour

The flagship of the hard discount model was the retail giant Daiei Group, which held the title of Japan’s top retail enterprise from the 1960s to the early 2000s, with group revenue reaching ¥300 billion at its peak. Founder Kōnai Chū admired the American retail model, believing that what happened in the U.S. would happen in Japan. Hence, in the 1970s, Daiei began investing in the discount store race, establishing Dmart in collaboration with Kmart, Kou’s to compete with Costco, Hypermart to rival Walmart, and BIG-A to emulate Aldi. However, all these formats failed successively, becoming deficit businesses contributing to Daiei Group’s losses. The failure of the hard discount model can be attributed to the following reasons:

1. Consumption is not just about buying things; it is also entertainment.

Hard discounts often sacrifice the shopping experience to reduce costs, with simple store decorations making the shopping process dull. Single-parent households do not consider hard discounts as destinations for weekend shopping with their children. For example, in the 1990s, the men’s restroom at Hypermart lacked urinals to save costs, using a stainless steel plate instead (similar to an old-fashioned public restroom).

2. Shopping requires “buying from multiple sources.”

Japan’s high population density and close proximity between channels result in low consumer mobility costs. Each channel introduces different enticing products every day, attracting consumers to make purchases. Consumers develop the habit of “buying from multiple sources.” However, the hard discount model aims for one-stop shopping, increasing the average transaction value under low profit margins. This does not align with Japanese consumption habits.

3. Insufficient production capacity makes vertical supply difficult.

An essential aspect of the hard discount model is the introduction of Private Brands. However, Japan’s production utilization rate has perennially remained insufficient, exceeding 100% (the surplus part is compensated for by the 996 culture). Manufacturers only accept channel orders during economic downturns and refuse to produce private brand orders with excessively low profit margins once the economy rebounds. This makes it challenging for Japanese channels to introduce cost-effective Private Brands for an extended period.

After 2000, the UK’s Tesco and France’s Carrefour both entered the Japanese market to promote the discount store model but withdrew within a few years. Walmart entered Japan through the acquisition of Seiyu supermarkets, transforming it into a discount store. However, since the acquisition, Seiyu has shown little growth, except for marginal profit increases. The hard discount model from Europe and America has struggled to take root in Japan.

Costco achieved significant success in Japan. Costco did not undergo localization adjustments in Japan, adhering to its own model. Ultimately, Japanese consumers learned how to shop at Costco. Housewives would drive together to make purchases, sharing oversized packaging with multiple families to get the best prices.

Competitor in Soft Discount: Rogers

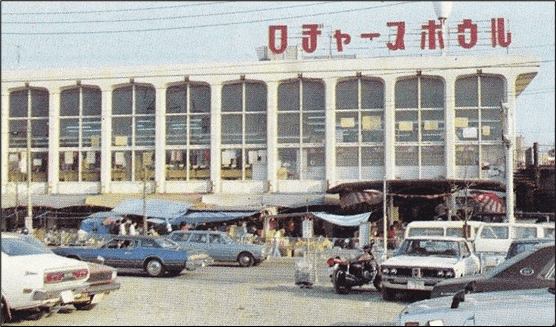

In the early stages, the soft discount model was more of a business transaction than a business model. It achieved ultra-low prices by selling surplus, clearance items, and financially mortgaged products, citing product shortages as a reason. Before the emergence of Don Quijote, several soft discount players appeared in Japan. The most representative of them was Rogers, established in 1973 during the Japanese oil crisis. Rogers capitalized on the opportunity of declining prosperity during the oil crisis, purchasing surplus stock from intermediaries and brand owners and selling it at low prices, gaining its first growth point. Early stores were mainly converted from bankrupt bowling alleys (as shown in the image), filled with thousands of SKUs. Rogers opened five stores in the suburbs of Tokyo, and in 1991, the company’s annual revenue reached a staggering ¥4 billion.

However, despite having the advantage of being a pioneer, Rogers failed to expand into other regions of Japan, establish its own supply chain and operating system, and become the industry leader. After several decades, it still maintains a scale of just over ten stores. This can be seen from the statement on the Rogers official website: “We were Japan’s first discount store established in 1973. In 2016, we opened a new store after a ten-year hiatus, and currently have 12. After the end of the economic bubble, we experienced significant constraints in our performance over the past ten years. We realized that the era of ‘Lowest Price First’ had long ended…… We maintain an attitude of being ‘cheaper than anywhere else’ but strive to ‘find the highest value within low prices,’ aiming to further grow and progress to become the consumers’ favorite company.”

Japanese retail scholar Toshiichi Watanabe sarcastically remarked in his research on the discount store format: “Due to the instability of the supply chain, soft discounts are difficult to manage operationally. Fast-selling items quickly sell out, while slow-moving items sit idle. The stores easily become ‘dumpsters,’ consumers are disloyal, only coming for deals, and the workload for store employees is high. The owner may make some small profits, but the company is left exhausted in the end.”

While soft discount store Rogers made a good deal by selling low-priced surplus goods, the instability of surplus product items prevented it from building a robust supply chain and management capability to expand nationally. Selling defective or problematic items cheaply for growth was a natural outcome, but it became a challenge that this model found difficult to overcome.

Answer to Question 2: Why Did Discount Store Players of the Same Era Fail?

- Hard Discount Players: Ignored cultural and social attributes in consumption, insufficient production capacity to supply Private Brands.

- Soft Discount Player: Unstable supply chain leading to an inability to scale, stores turning into dumpsters.

In the next issue, we will address how Don Quijote overcame the shortcomings of the soft discount model, the core logic behind Don Quijote’s dense display, and how internal management at Don Quijote maintains a competitive edge. Stay tuned to unravel the structural advantages of this company.

References

-

Toshiichi Watanabe. (1994). “Discount.” (Japanese)

-

Kazumasa Yamazaki. (1987). “The Birth of Soft Individualism – Aesthetic of Consumer Society.” (Japanese)

-

Katsutoshi Morita. (2004). “Battle History of Distribution – Comparative Analysis of Daiei, 7-Eleven, and Ito-Yokado.”

-

“Riding the Crest of the Economic Cycle, Innovation, and Romance of Discount Stores: Comparative Study of Japanese and American Discount Stores and Benchmarking of Japan.”

-

“From Incremental Competition to Stock Competition Transformation: Strategy under the Influence of Economic Cycles (Part 1) Price Disruptors and Retail Revolution: Daiei and Nakajima Koko.”

-

“The Three Entrepreneurial Periods of Nissin Foods: Seizing the Dividend and Surviving!”

-

Mr. W, Former Special Advisor to the Founder of Don Quijote

-

Mr. Y, Former Human Resources Manager at Don Quijote

-

Mr. A, Former Executive in the Retail Division of the Seibu Group’s FamilyMart Convenience Stores