I’m very pleased to have the opportunity to speak today on behalf of GenBridge Capital, at a time when it’s been a year since the end of the pandemic and China’s retail industry stands at a major turning point. In response to this shift, the title of my talk is: “Three Major Transformations in Retail Chains During the Consumer 'Buyer’s Market' Era: Discounting, Localization, and Vertical Integration.”

GenBridge Capital is a consumer-focused investment fund with a vision to invest and support China's “next generation of consumer champions.” We have five defining features: founded with the backing of JD — China’s largest retail company; the most consumer-focused fund in the country; acting as earliest and largest investors; deeply embedded in the industry; and known for being the most problem-solving investors.We focus on two major investment themes: “next-generation national chains” and “next-generation national brands,” particularly in three sectors — food, home and furnishings, and lifestyle.

The “community-based national chains” we’ve invested in collectively operate over 20,000 stores, with a combined annual sales scale exceeding 60 billion RMB, expected to surpass 100 billion in three years. I’d like to share some insights based on their practices.

Let me start with a central viewpoint: China’s retail industry has entered a “buyer’s market.” Over the past 20 years, China’s urbanization, digitization, and entry into the WTO helped it evolve from a supply-constrained economy to one of surplus—a buyer’s market.

We can draw a parallel with Japan, which, after experiencing rapid growth in the 1970s and 1980s, entered a period of overcapacity. In its “Lost Three Decades,” capacity utilization kept declining. Similarly, in China, post-COVID changes in demand are very evident — everyone can feel the cooling of consumption. Consumers are tightening their wallets. From past trends of consumption upgrades, we now see a shift toward price sensitivity and increasingly segmented needs.

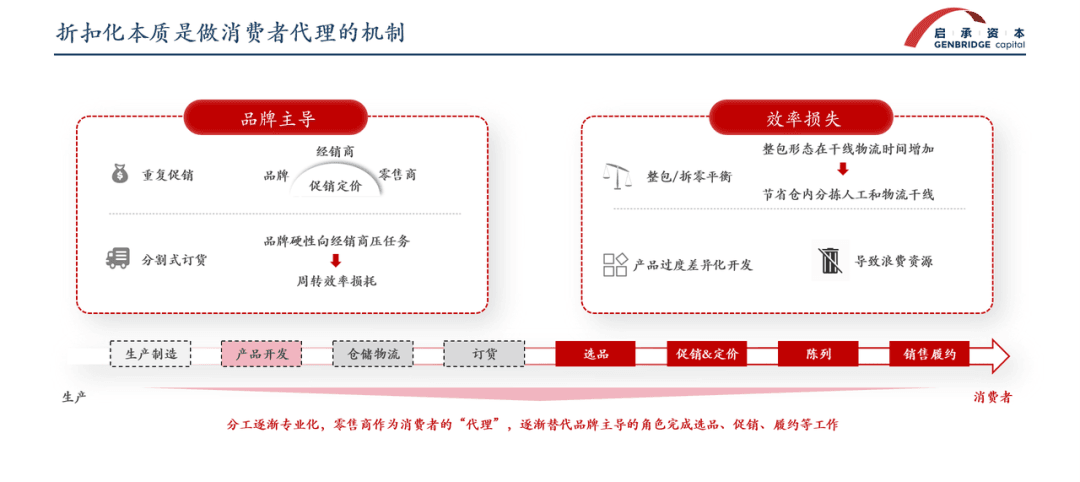

Looking at developed countries, when supply is limited, brands hold the power; but when supply exceeds demand, retailers gain the upper hand. This has disrupted the brand-driven retail model in China. In the traditional ecosystem, everything served brands: major players like P&G would push a vast number of SKUs through heavy channel coverage, relying on full-price promotions in supermarkets. But this system is highly complex, with an equally complex cost structure — brands take on much of the promotional burden, even hiring their own in-store promoters. As retail evolves, this brand-dominated model is bound to fade.

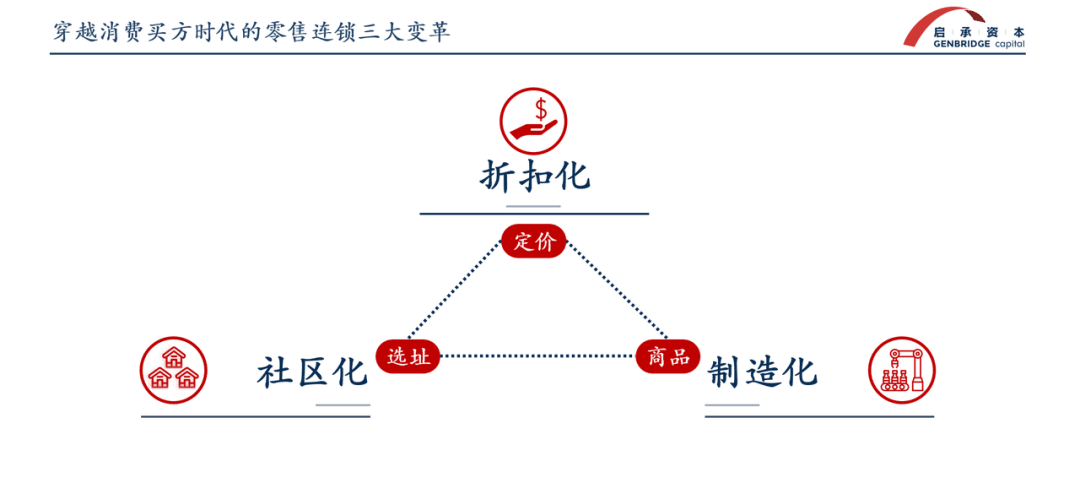

In today’s buyer’s market, we see three clear transformations in retail chains: Retail is moving toward discounting, community localization, and manufacturing integration in its pricing, store locations, and product strategies.

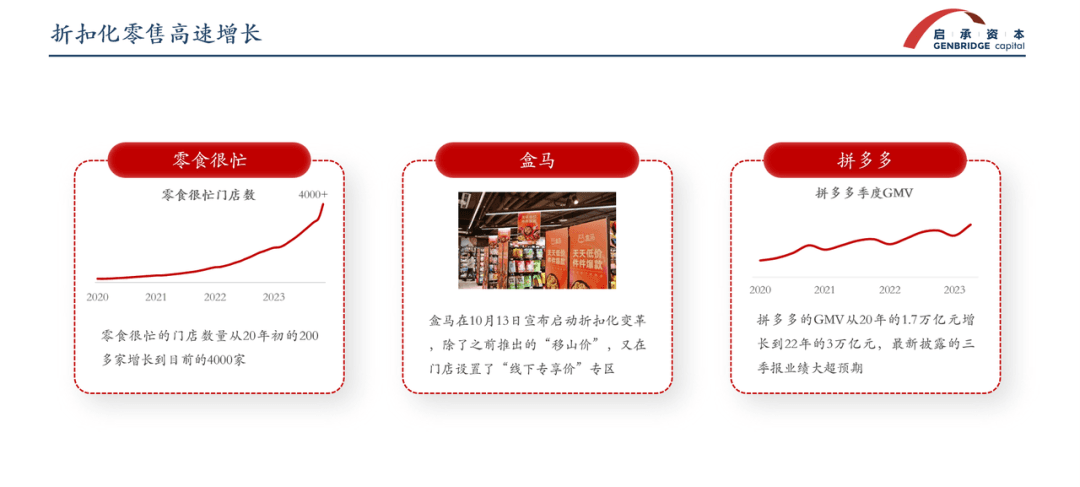

Discount retail has seen explosive growth this year, becoming one of the hottest topics in consumer trends: Snack Is Busy ("零食很忙") has become a retail phenomenon, rapidly expanding to over 4,000 stores. The entire discount snack sector is booming. Freshippo launched aggressive price cuts under its “moving-mountain price” campaign. Pinduoduo even surpassed Alibaba in market cap at one point.

The essence of discounting is to act as a consumer agent. New-generation retailers must integrate upstream across the entire value chain, gradually replacing brands as the lead actor—handling product selection, promotion, fulfillment, etc.

In the past, industial ecosystem revolved around brands—but the brand-driven model incurs massive inefficiencies. Every brand tried to build its own distribution system—replacing retailers in ordering, promotion, product selection, and logistics. This includes “deep distribution,” where dealers reach towns and villages, ensuring shelf presence and sales. This approach results in inaccurate orders, redundant product launches, and countless ineffective promotions.

The most basic logic of retail is, whoever is closest to the consumer should own more responsibility and initiate the supply chain. As retail chains transform, they must take on more roles—streamlining product selection and building stronger single-product management capabilities.

Another key aspect is value-for-money and demand stratification. While low prices have been very effective this year—bringing products back to their essential value—over a longer time frame, consumers will still seek value-added services. Ultimately, retailers must segment consumer demand and respond accordingly.

GenBridge has invested in two companies directly related to hard discount retail: Snack Is Busy and Duoletun. We began engaging with Snack Is Busy around 2019 and became their first-round investor in early 2021. At the time, many didn’t see them as a hard discounter—more like a highly competitive convenience store.

But we believed their core was hard discounting. Founder Mr. Yan is a master of subtraction—he streamlined the snack category by sourcing directly from factories, used lower markups, reduced unnecessary transport and unpacking steps, and cut costs to deliver value back to consumers. This aligns with the hard discount philosophy of efficiency.

Hard discounts first gained traction in offline snack retail largely because of inefficiencies in that category. Snacks are mid-frequency purchases, slower-moving than other food products, and had large price markups in traditional supermarkets.

Looking ahead, we believe hard discounting will expand to all categories. Duoletun is a prime example: it covers broader categories like staples and fresh produce, following a model similar to Europe’s ALDI. It’s pioneering hard discounting in comprehensive food categories like rice, flour, grains, and oils.

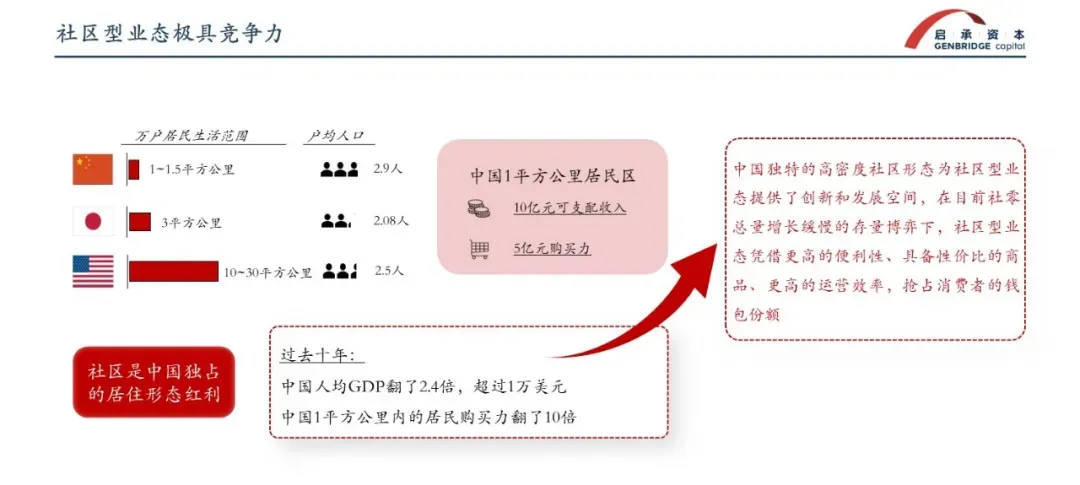

On community-based retail, we’ve seen a surge in small community chain stores opening within residential neighborhoods over the past two years. China, with its high population and housing density, is unparalleled globally. There are more than 300,000 residential communities across the country, typically with a floor area ratio around 2.0, meaning these are relatively compact and enclosed living environments. As a result, purchasing power and foot traffic are highly concentrated within communities.

Since 2015, many people have moved into high-rise apartment complexes in new urban districts. As occupancy rates have increased, purchasing power has risen significantly. Today, one square kilometer of urban China represents about 500 million RMB in consumer purchasing power—just 1% of that is enough to support a store. Yet in many cases, there are no nearby amenities—no wet markets, supermarkets, or shops within walking distance. This lack of local retail infrastructure has created huge opportunities for community-based stores.

Among GenBridge Capital’s portfolios, there’s Qiandama (focused on fresh produce), Guoquan (focused on frozen foods), and Snack Is Busy (focused on snacks). These vertical category brands essentially relocate supermarket goods to people’s doorsteps. This kind of format brings cheaper goods and closer proximity to consumers—helping them walk less and buy smarter. In essence, it’s a boost in efficiency.

Community-based formats have changed the operating model of many retail chains:

First, we see dense store openings—you’ll find the same store at many community entrances, intercepting consumer traffic into a dense, grid-like, localized network.

This is different from Japan, where dense store clustering is usually found in commercial zones, whereas in China, it’s community-centric.

Second, if you want to attract consumers from farther away and run larger stores, you must offer more differentiated value.

Big-format retailers need more competitive pricing and differentiation—Duoletun offers prices even lower than Pinduoduo; Sam’s Club has unique private-label products.

Third, online tools further empower community-based stores to increase per-store output.

With most stores sized between 60 to 150 square meters, physical space and street traffic are limited. So it’s critical to enhance SKU offerings, product effectiveness, and staff productivity through digital tools.

Take Qiandama, for example: in a residential community with 3,000 households, a single store can attract 500 to 600 daily customers, most of them repeat buyers. The key to building a defensive moat is earning the long-term trust of local residents and capturing the largest share of their wallets.

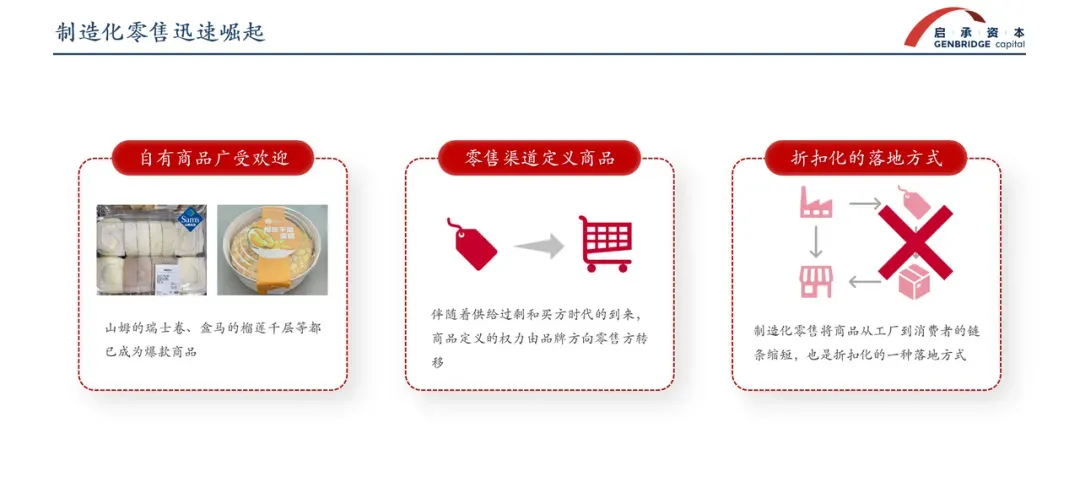

Finally, we come to the rise of manufacturing-oriented retail. Retailers don’t necessarily need to run their own factories, but they do move upstream—influencing product definition, order planning, and raw material selection.

This is the practical application of discounting, where retailers—having gained strong insight and product-selection capabilities—can define products based on consumer demand, shortening the value chain and improving efficiency.

This “retail manufacturing” approach enhances both price competitiveness and product distinctiveness.

Here are a few examples: Freshippo Fresh promotes its own private-label milk, significantly improving price competitiveness. Pangdonglai launched a unique mooncake product that sold out immediately upon release.

Japan offers a good reference point: as consumer demand becomes increasingly segmented, retailers must offer more tailored products.Japanese brands and channels have formed “manufacturing-retailing alliances,” where they plan together: brands launch 100 products annually for a given channel, the channel filters them down to 10, and 2 of those become long-term hero SKUs. This stable product pipeline reduces friction in product launches and ensures operational efficiency.

Another case: Guoquan’s collaboration with upstream supplier Daixiaji (a seafood processor) is also a success story. Guoquan, based on consumer insights, customized shrimp balls and shrimp patties with Daixiaji in Beihai, Guangxi—ensuring high shrimp content and strong value-for-money. The products were a hit in Guoquan stores, and Daixiaji also gained new clients in non-Guoquan channels, thanks to the product’s quality.

To conclude, we’ve entered a “buyer’s market” era in consumer spending, and China’s retail industry is undergoing three structural transformations: Discounting, Localization, and Manufacturing Integration. At its core, the shift returns to one fundamental truth: Retailers must place consumer needs at the center, becoming agents for consumers, and continuously iterating their formats around those needs.

Today, China’s offline retail revolution is just beginning. For the past 20 years, China has lacked strong single-product management and clear merchandising capabilities. These gaps will be filled by the rise of a new generation of retailers. And as their capabilities grow, so too will the sophistication of retail formats. For example, OK Store once tried to bring Europe’s hard discounter ALDI into Japan—but failed early on. It wasn’t until they added fresh food and strengthened frozen goods that the format took off and saw rapid growth.

Compared to Japan at that time, China today offers a much larger market and more advanced retail infrastructure. Still, successfully localizing overseas formats requires industry-wide wisdom. We look forward to seeing our peers in the Chinese retail industry—through continuous capability building—create even more advanced and innovative retail models.