For China's consumer entrepreneurship and investment, Japan's retail industry serves as a valuable benchmark for research and learning.

China and Japan share similar cultural environments, lifestyles, high-density urban structures, economic development cycles, and demographic evolution patterns. This positions Japan's advanced and mature retail sector a mirror for the future evolution of China's retail industry.

However, history does not develop in a linear path, and simply applying the "time machine theory" to compare China and Japan's consumer markets would be one-sided. Beyond their similarities, these two markets also exhibit significant differences.

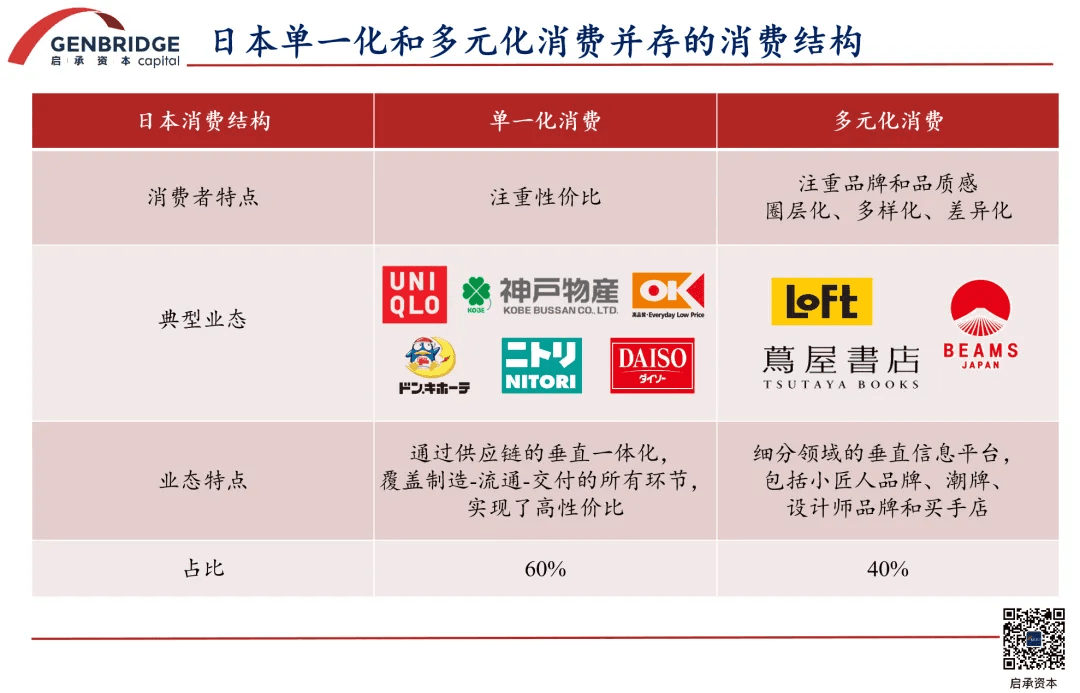

This was particularly evident in the recent "worst-ever" 618 shopping festival in 2024, which clearly showed that China market is currently dominated by low-price, single-dimensional consumption. In contrast, since the 1980s and 1990s, Japan has gradually evolved into a consumption structure where efficiency-driven mass consumption coexists with interest-based niche consumption.

Many say that China's consumer market is following in Japan's footsteps, but is that really the case?

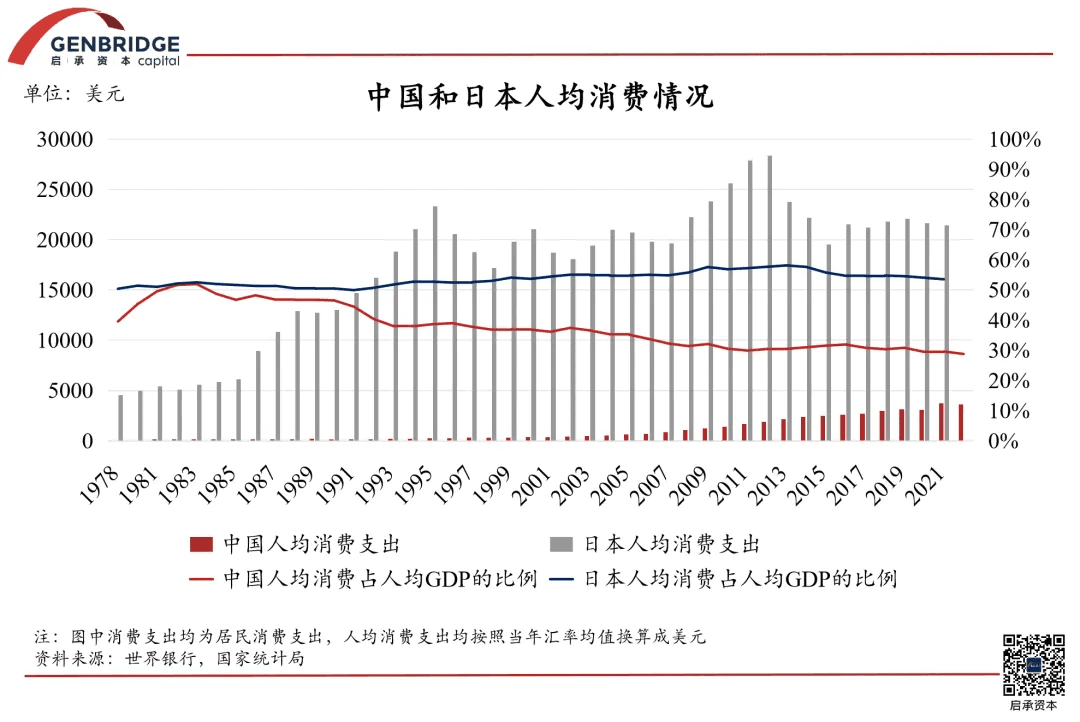

First, per capita GDP figures are vastly different—China's is four to five times lower than Japan's while both Japan in the 1980s and 1990s and China today are experiencing economic downturns.

A more critical indicator is the share of consumption in GDP. In China, per capita consumption accounts for less than 40% of GDP, whereas in Japan, it ranged from 50% to 60%. This means that overall, Japanese consumers had a stronger desire to spend. Even when their purchasing power declined, it was unlikely that they would entirely stop consuming. They would simply cut back on certain expenditures accordingly.

Secondly, differences in market size lead to various market phenomena.

In China, product price ranges are much wider. For example, the price of fresh milk at Freshippo ranges from 2 RMB to 38 RMB—a disparity that would not occur in Japan. In Japan, milk prices generally fall between 10 RMB and 20 RMB, with a price range difference of about twofold, whereas in China, the difference can be as much as tenfold.

Additionally, the complexity of logistics also varies.

Japan has faster and more efficient logistics with its much smaller land area. For instance, freshly caught seafood from coastal areas can reach store shelves within 24 hours, and convenience store deliveries cover a smaller, more manageable radius. As a result, Japan’s distribution system is simpler, often involving only one or two levels of wholesalers. In contrast, China’s distribution system is much more intricate, extending into county-level markets and even deeper layers.

Consumer companies and businesses adopt different strategies as consumer perceptions vary across countries during each other's economic downturns.

In China, since per capita consumption has always been low and there is an oversupply of production capacity, the first wave of competition is inevitably centered around low-price strategies. Businesses are focusing on extending product offerings based on cost-effectiveness while addressing some personalized needs, but not primarily through product innovation.

In contrast, Japan had already entered an era of abundant supply in the 1980s. Companies rapidly expanded their market presence and developed a vast array of new products, leading to an explosion of creatively designed, eye-catching items—somewhat similar to China's consumer boom in 2019.

By the 1990s, Japan underwent a cycle of retail industry transformation. Some businesses collapsed, while others rose to prominence. These emerging companies could generally be categorized into four types:

The first type includes companies that leveraged the supply chain advantages brought by Chinese manufacturing to succeed. They adopted the SPA (Specialty Store Retailer of Private Label Apparel) model to achieve high cost performance. Examples include Uniqlo, NITORI, Kobe Bussan, and 100-yen stores like Daiso.

The second type consists of select shops that thrive in a saturated market by continuously offering fresh, interesting, and non-standardized products. This category includes LOFT, Tokyu Hands, ABC-Mart (which specializes in footwear), and fashion select shops like BEAMS. These businesses use flexible product selection to adapt to changing trends.

The third type consists of category killer stores or specialty stores, including drugstores and home appliance retailers. These channels disrupted the traditional brand-owned retail or sales channels by reorganizing market products through a retailer-driven approach, with drugstores and home appliance stores being the main examples.

The last type is the soft discount model, represented by retail chains like Don Quijote.

Single Market vs. Diverse Market

During the 1980s and 1990s, Japan witnessed two distinct consumer trends.

One was the standardized, vertically integrated brand like Uniqlo, focusing on cost performance. The other is characterized by diversification, where a multitude of Japanese artisan brands emphasize craftsmanship and quality, alongside the rise of streetwear brands. This has led to market stratification, diversification, and differentiation, with a strong emphasis on brand-oriented consumption habits.

One manifestation of this diversity was the success of niche and specialized corporations. Another was the significant expansion of product variety within retail channels to meet consumers' diverse needs.

A prime example of diversification is Tsutaya Bookstore, whose growth was initially driven by Japan’s railway-centered urban structure. Tsutaya stores were strategically located in train stations, ensuring high traffic from commuters.

Tsutaya developed two distinct business models building on this foundation:

In fifth-tier cities in Japan, Tsutaya stores typically combined bookstores with CD/DVD rental sections. They offered an extensive selection of magazines, and their membership system tracked consumer purchases. In major cities like Tokyo, Tsutaya evolved into a curated lifestyle store, incorporating cafés, art, and crafts, focusing more on experience.

Tsutaya Bookstore resembled Xiaohongshu by catering niche interests and providing specialized information in some ways. Its membership system collects and categorizes consumer data, which can be shared or utilized by other corporations and platforms.

Another exemplary sample of diversification is convenience store in Japan.

On one hand, due to the limited space, each display spot is exceedingly valuable. Stores aim for each spot to generate maximum sales performance, leading to swift product replacements when items fail to guarantee high turnover.

On the other hand, convenience stores have permeated the very capillaries of urban life. They are not merely supplementary businesses but an indispensable part of the Japanese consumer's daily routine. Urban residents, in particular, might visit a convenience store twice a day, amounting to as many as 14 times a week.

To maintain a sense of freshness for consumers, convenience stores must constantly adjust their product selection. As a result, the product turnover rate in Japanese convenience stores is extremely high, with most items having a survival rate of less than 30% after the second year. This rapid cycle of product introduction and elimination requires convenience stores to have a strong product planning department.

However, these trends toward diversification are unlikely to become the mainstream of the China's consumer market.

First, China's consumer society differs from Japan's. The concept of a "lower-tier market" does not exist in Japan, and the classification of cities is not as distinct as in China, where cities range from first-tier to fifth-tier. In fact, disposable income in rural areas of Japan can be higher than in cities, and it's common to see luxury cars and specialty modification shops in rural regions. This means that Japan's "diversified" consumption trends have a broader market space due to generally higher income levels.

Second, in China, online platforms have taken over the role of vertical information hubs. On platforms like Xiaohongshu, consumers can find almost any consumption-related information. As a result, lifestyle select shops like Loft and Tsutaya Books, which rely on curating information as a differentiator, struggle to establish an exclusive information advantage.

Lastly, compared to Japan, China's urban structure is characterized by "high-density concentration," with large populations living in massive residential complexes. This allows e-commerce to achieve optimal delivery efficiency, making offline shopping experiences less convenient in comparison. Since e-commerce platforms provide fully transparent information, the advantage of differentiated product offerings is significantly diminished when flattened by e-commerce.

Some Japanese experiences are difficult to replicate

If the ratio of standardization to diversification in Japan is approximately 6:4, in China, it is likely closer to 9:1.

The "6" in Japan's 6:4 ratio includes companies such as Uniqlo, Nitori, Kobe Bussan, and DAISO. These companies share a common characteristic: they offer high cost-effectiveness by leveraging vertically integrated supply chains that cover everything from manufacturing to distribution and delivery, ensuring competitive price-performance ratio.

However, if we trace the historical development of these Japanese corporations, we will find that many of their experiences are difficult to replicate.

In Japan, the core driving force behind standardized consumption was the advantage of China's supply chain in the era of globalization. Some Japanese companies leveraged this advantage to enter the Japanese market at lower costs. Additionally, factors such as strong in-store sales capabilities and product development expertise further reinforced their success.

Tadashi Yanai once stated that Uniqlo's growth should be attributed to China and the interplay between the textile industries of Japan and the United States. At the time of Uniqlo's inception, the majority of Japanese apparel companies were on the brink of significant crises, and numerous textile professionals were struggling to find work.

Meanwhile, in the 1980s, many township enterprises along China’s coastal regions began transitioning to the "three-plus-one trading-mix" model. Uniqlo seized this opportunity by integrating Japanese technology with China’s manufacturing capacity, educating Chinese suppliers to produce clothing that met Uniqlo’s standards. Thanks to China’s low labor costs, Uniqlo was able to achieve its first stage of growth with highly competitive pricing.

However, this logic no longer applies to today’s China. In a country with such immense production capacity, the supply advantages that Japan once found scarce—such as cost and production differentials—are no longer rare.

In other words, while today's supply chain dividends are widespread, they do not create an absolute competitive advantage for businesses. As a result, many businesses are forced into relentless price wars, leading to chaotic and unsustainable market conditions.

What are the challenges of entrepreneurship in China?

The Chinese market is transitioning from a seller's market to a buyer's market, shifting from a supply-driven to a demand-driven model.

In the era when channels and supply were the primary drivers, sales were the key factor—“whoever could get their products onto the shelves” held the competitive advantage. This, combined with a one-size-fits-all advertising slogan, defined China's retail and distribution paradigm up to this point.

However, today, consumer demand has largely been met. Traditional products no longer create new demand or effectively attract consumers to make purchases. At the same time, as consumer expectations for future income decline, people are tightening their spending and becoming more cautious in their purchasing decisions.

At this stage, the key capability for retailers is no longer just competing with peers to offer the lowest prices. Instead, they must shift towards demand-driven strategies—analyzing consumer needs and working backward to influence upstream suppliers, actively shaping demand rather than just responding to it. This goes beyond product development; it requires a complete restructuring of various operational aspects, such as cost strategies and shelf management.

Take the example of Lawson’s popular fried chicken product in Japan. It originated from a proposal by the frozen food company Nichirei. Nichirei identified a specific consumer demand and proactively suggested the idea to Lawson, leading to the creation of this hit product.

Many Japanese retailers take a proactive approach to product development by studying whether the products on their shelves cover core demographics and key price ranges. This allows them to work backward to propose targeted solutions. However, in China’s more competitive and transactional retail environment, this model is relatively rare.

Secondly, the intensity of price wars in China is something the Japanese market has never experienced. In China, e-commerce has scaled up and centralized access to over a billion consumers. Brands can efficiently connect with this vast audience online, making price an explicit and direct competitive tool.

However, in recent years, we've seen traditional e-commerce platforms struggling, while content-driven e-commerce like Douyin (TikTok in China) has surged in popularity. This shift indicates that the dividends of pure price competition have reached their limit.

On a platform like Tiktok, it’s not just about offering low prices—it also generates massive amounts of interactive data. Brands can identify their consumers more precisely and use the platform’s broad bandwidth to deliver richer content to them. In a sense, Douyin serves as a new-generation platform for developing and communicating around consumer demand, setting it apart from other channels.

Lastly, Japanese companies' success often builds on specific advantages tied to their geography and commercial environment. For example, Uniqlo's growth began with its supply chain advantages, followed by strong product development and marketing capabilities.

In contrast, today’s Chinese companies need to navigate multiple challenges simultaneously and demonstrate comprehensive excellence. In a vast market with diverse consumption patterns, rapidly changing trends, and the added complexity of e-commerce, the challenges faced by Chinese businesses are far greater than those encountered by Japanese companies in the past.