Changsha remains a landmark that cannot be overlooked when discussing consumer in China.

With a population of over 10 million and a GDP ranking 15th nationwide, the city boasts one of the most vibrant nighttime economies, the highest concentration of flagship stores, and a large number of young people who refuse to sleep. Over the past decade, Changsha’s population has grown by nearly 3 million—equivalent to the urban population of Singapore.

In early September, GenBridge Capital, together with more than 40 friends from consumer investment sector, took to the bustling streets of Changsha. What we witnessed was not just dazzling innovations in retail experiences and themed businesses but a deeper question—what are the fundamental forces driving Changsha’s thriving consumer market?

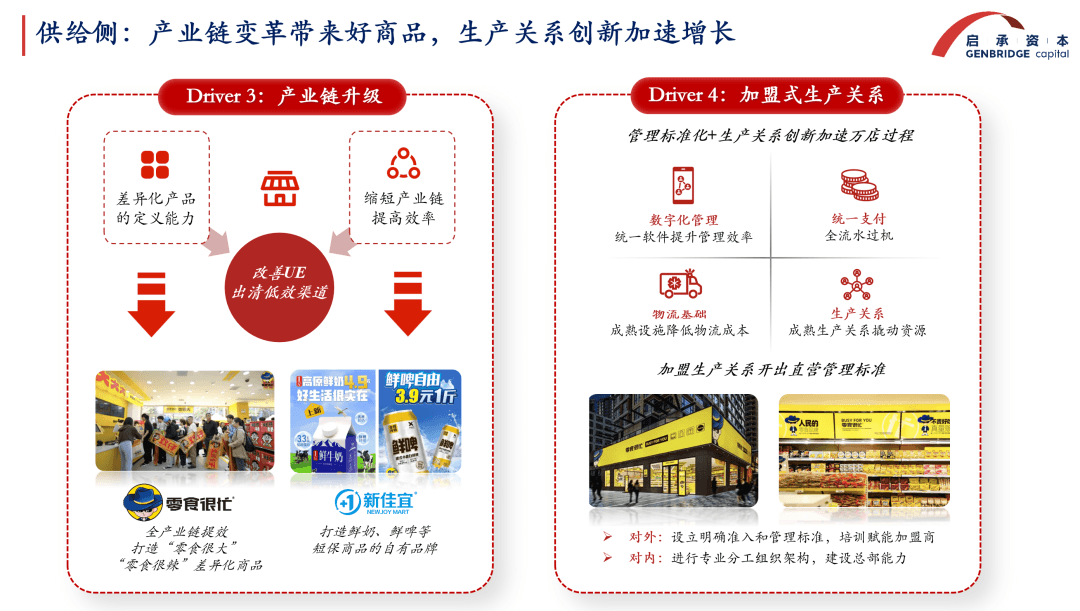

At Snack Is Busy, we saw retailers collaborating closely with suppliers to bring consumers products with both emotional appeal and added value. At New Joy Mart, we observed a new generation of empathetic and community-focused retailers expanding upstream and steadily penetrating county-level markets.

Starting from Changsha, we have every reason to believe that China's consumer market will continue to thrive. We are witnessing a structural evolution in China consumer and are confident in identifying the opportunities and direction ahead.

The content of this article stems from a sharing session during Inheritance Capital's Changsha trip. We will delve into the following questions:

- What insights can Changsha's experience offer for the domestic retail industry?

- What can China's retail sector learn from Japan?

- From a historical perspective, what structural changes is China's retail industry currently undergoing?

Changsha: A standout model in China's retail sector

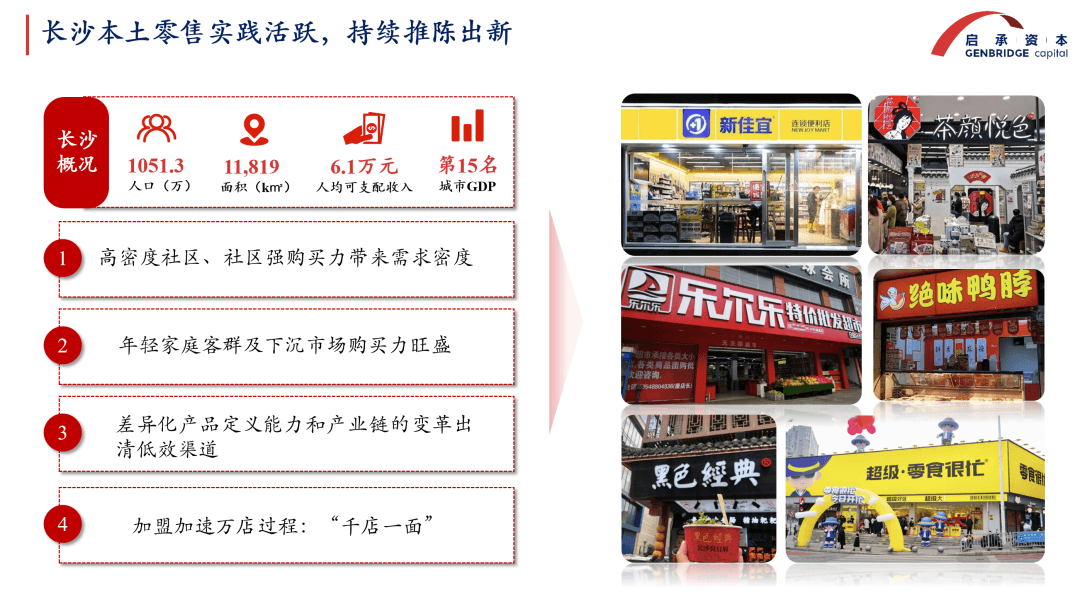

Behind Changsha's diverse retail formats, several trends and shifts are evident:

From the demand side, Changsha exhibits remarkably high demand density. The purchasing power within Changsha's, and indeed China's residential communities is exceptionally strong. High-density neighborhoods can support numerous "category killer" stores of single-category with high purchase frequency and low average order value, with family-centric consumers forming a critical part of these community-based retail models.

At the same time, Changsha's commercial districts are highly concentrated, such as the Wuyi Square and Wanjiali shopping areas. These hubs, popular among influencers and tourists, have given rise to retail formats tailored to their dynamics.

In terms of demand breadth, counties surrounding Changsha are vibrant markets where demand is underserved.

In the past, a packaged food product had to pass through multiple intermediaries—suppliers, brand owners, primary and secondary distributors—before reaching retail stores, resulting in a markup of nearly 2 to 2.5 times. The transaction chain in lower-tier cities was even longer than in first-tier cities, meaning consumers in these markets sometimes paid more for products like Coca-Cola than those in metropolitan areas.

Today, by shortening this supply chain, transaction efficiency has improved significantly. Retailers can attract larger customer bases in county-level markets by offering better prices and products, thereby upgrading local consumption. This explains why retail expansion in first-tier cities requires widespread presence, while in lower-tier cities, it demands dominance in key locations.

The vast opportunities in lower-tier markets have nurtured many successful retailers.

In Xuchang—a city with half the GDP and population of Changsha—Pang Donglai has emerged as a standout. With just 13 stores, Pang Donglai achieves an average daily sales of around ¥1.05 million per store, attracting roughly 10,000 daily visitors per location.

Similarly, Xiangyang, another city with economic indicators about half of Changsha's, is home to Good Neighbor, a chain with over 90 stores and richer retail formats, generating ¥450,000 in daily sales per store.

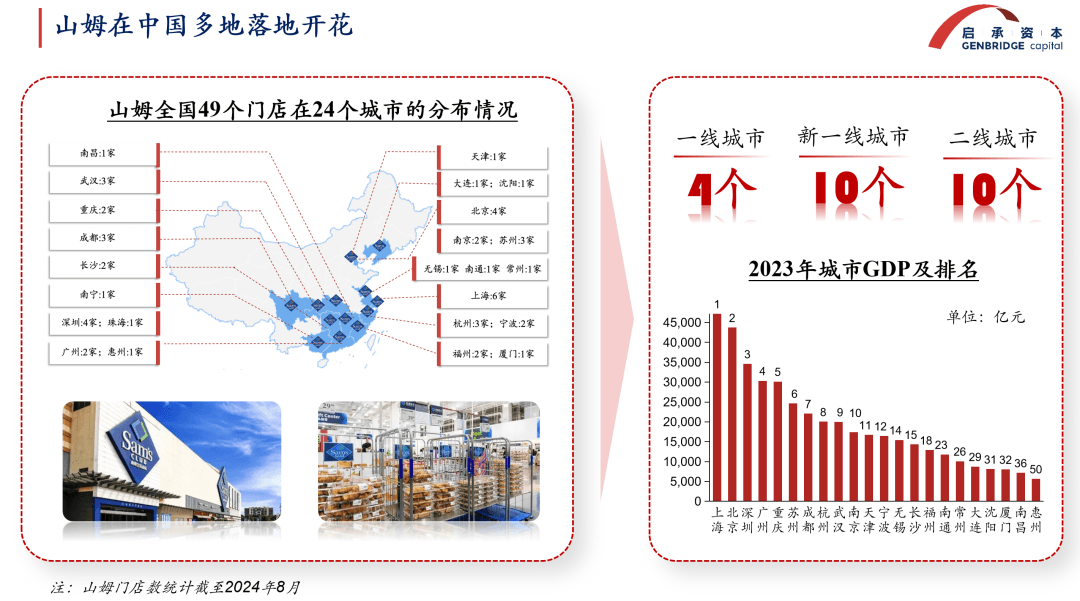

Even retail giants from first-tier markets are now actively expanding into lower-tier cities. Sam’s Club’s store distribution in China shows that, beyond top-tier cities, emerging first- and second-tier cities—including Huizhou, Nanchang, and Nantong, which may not rank high in GDP—are demonstrating strong consumption vitality.

Amid discussions of declining hypermarkets, retail slowdowns, and consumption downgrading, the maturation of community infrastructure has enabled the flourishing of small-format retail.

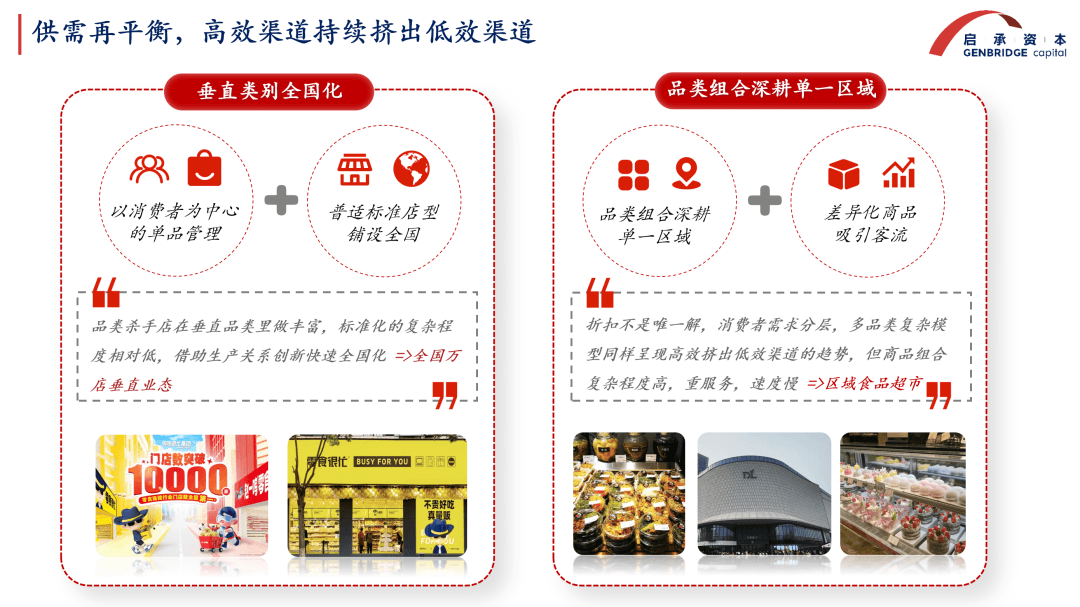

Single-category small stores have the potential to scale to 10,000+ locations nationwide. Their rapid expansion is possible because they focus on standardized product categories with lower operational complexity and leverage strict franchising models for nationwide rollout.

This reflects a broader trend over the past two decades in China’s retail sector: efficient formats continually displacing inefficient ones.

Historically, retail progress has been a story of efficient models relentlessly outperforming inefficient ones.

Historically, retail progress has been a story of efficient models relentlessly outperforming inefficient ones.

When traditional department stores and supermarkets operated on 40-50% gross margins with lengthy procurement cycles, Walmart revolutionized American retail by adopting 25% margins, faster inventory turnover, and direct wholesale purchasing—establishing dominance in smaller cities. Later, Costco redefined the model again with its 13% gross margin and 2% net profit approach.

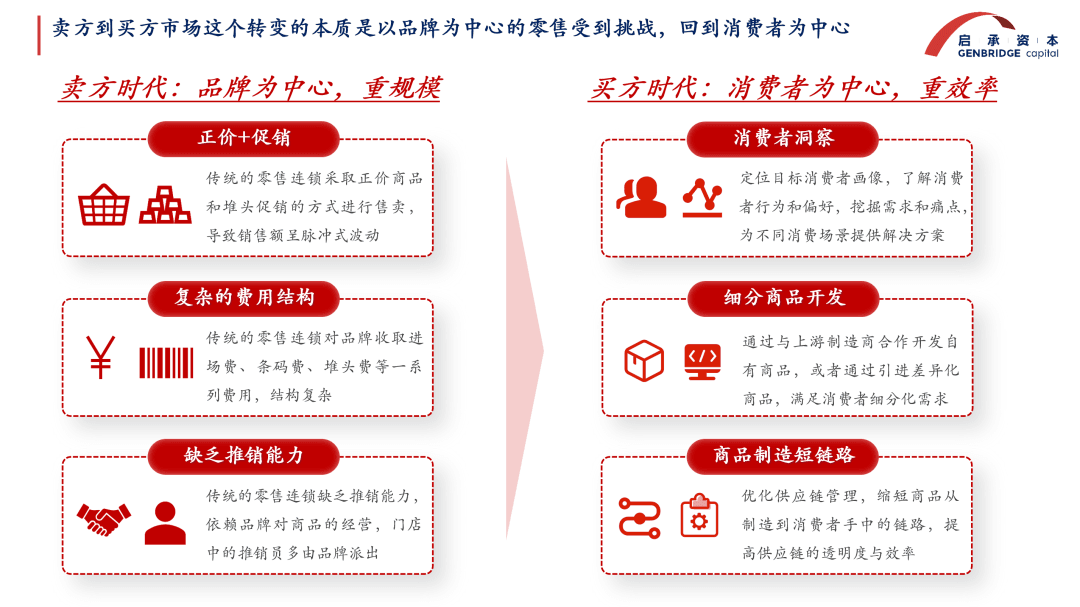

During era of seller's market, when supply trailed demand, retailers primarily served as platforms for brands, profiting through slotting fees and promotional charges. But as markets saturated and oversupply emerged, consumer preferences became paramount.

A new generation of retailers has risen to meet this shift. By streamlining supply chains, they deliver greater efficiency—passing cost savings to consumers while curating high-value product selections to attract and retain customers.

New Joy Mart's private brand (PB) products exemplify this model. Rather than relying on traditional vendor fees, these retailers now profit through strategic merchandising and rapid inventory turnover.

Technology and franchising accelerate the change of retail industry.

Our field research at Snack Is Busy stores revealed how innovation is transforming operations:

Remote monitoring systems using in-store cameras enable efficient merchandising and staff management

Digital planogram systems precisely guide product placement and pricing

AI-powered checkout significantly improves transaction speed

These advancements in digital management, unified payments, and logistics—combined with franchise model innovations—allow join-in stores to achieve corporate-operated standards. The result? Retailers can better match consumer demand, delivering superior value that drives traffic to next-generation retail channels.

Today's Changsha represents this dynamic equilibrium—a vibrant marketplace where evolving supply and demand have created a diverse, thriving retail ecosystem where multiple formats flourish simultaneously. The city stands as testament to retail's ongoing revolution in China.

What can China's retail sector learn from Japan?

While Changsha represents a uniquely vibrant retail market in China, the broader Chinese retail landscape still faces significant challenges—particularly when compared to Japan's highly developed retail industry.

For example, compared to Japan, where the retail industry is highly developed, doing retail in China comes with many challenges that need to be overcome.

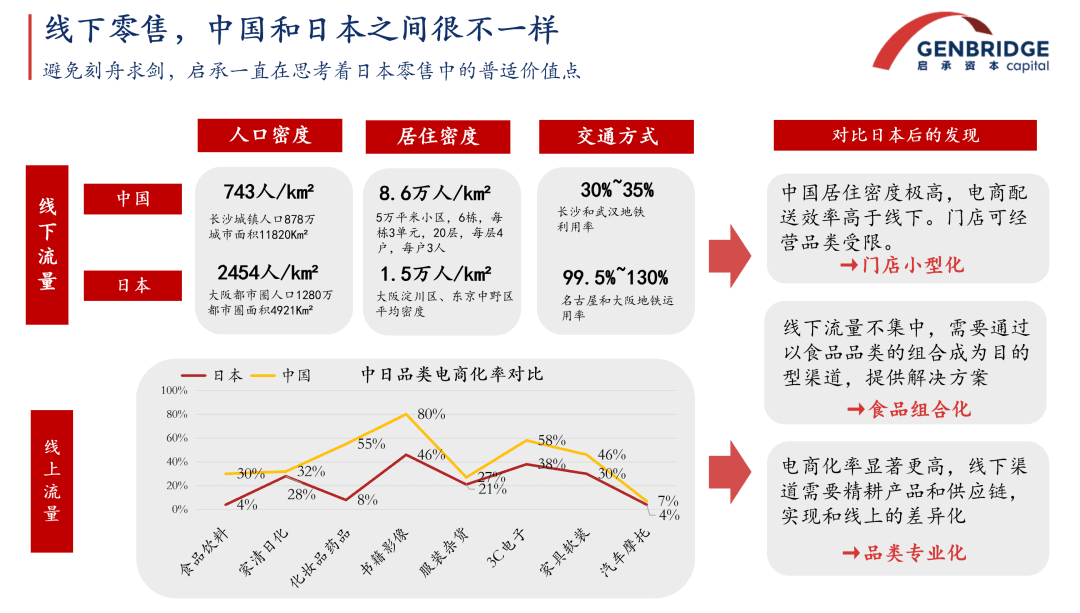

The biggest difference between the two countries is that Japan has high pedestrian density, while China has high residential density. In terms of transportation and urban planning, Japan relies primarily on railways, and retail businesses are concentrated along railway lines to attract foot traffic. In contrast, China’s residential communities accommodate the main flow of people, leading to a different retail layout.

At the same time, China’s e-commerce penetration rate is significantly higher than Japan’s, with online retail already covering many consumer needs. As a result, offline retail in China must work hard to differentiate itself by creating value that e-commerce cannot easily fulfill.

This has led to increasing competition in China’s offline retail sector. Stores are becoming smaller, moving closer to residential communities, and continuously refining their product offerings and services to attract customers.

Despite economic fluctuations and major transformations, one thing remains unchanged in retail: retailers, as consumer agents, must continuously innovate to meet evolving consumer demands.

Over the past 30 years, Japan’s average annual household income has declined, yet during the pandemic, discount stores, drugstores, and convenience stores experienced significant growth. This reflects key consumer concerns in Japan: fear of poverty, fear of illness, and fear of inconvenience.

Fear of poverty drives the success of discount stores.

Fear of illness fuels the demand for drugstores, as people seek better health solutions.

Fear of inconvenience makes convenience stores essential for quick meal solutions.

The retail industry has gone through shocks and drastic changes, but one thing remains constant: retailers, as agents of consumers, need to continuously meet these changing consumer needs through product innovation.

The most noteworthy experience in the Japanese retail industry is the strategy of continuous product differentiation.

In the early stages, Japan’s private-label (PB) products were primarily focused on low prices to attract more customers. However, as retailers faced challenges such as an aging population, shrinking household sizes, and reduced commercial zones, they shifted in the past decade from low-cost strategies to high-quality, problem-solving products.

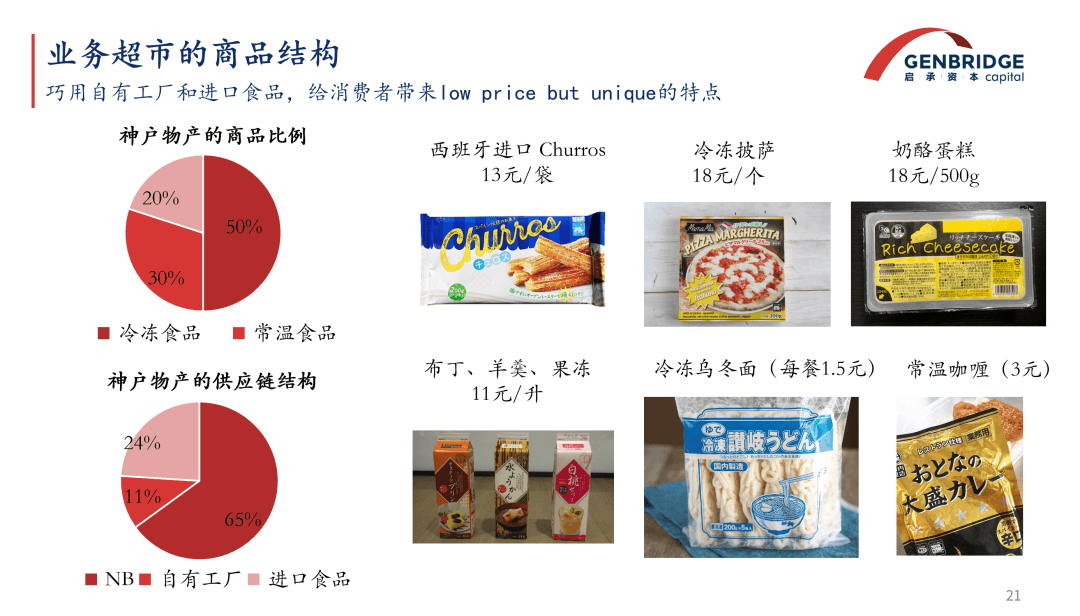

For instance, Kobe Bussan, a Japanese retailer, emphasizes in-house production of PB products. Their private-label goods are 50-60% cheaper than those in convenience stores. Beyond affordability, they also differentiate their products, avoiding direct competition—for example, by importing frozen pizza directly from Italy or using tofu packaging machines to produce cakes.

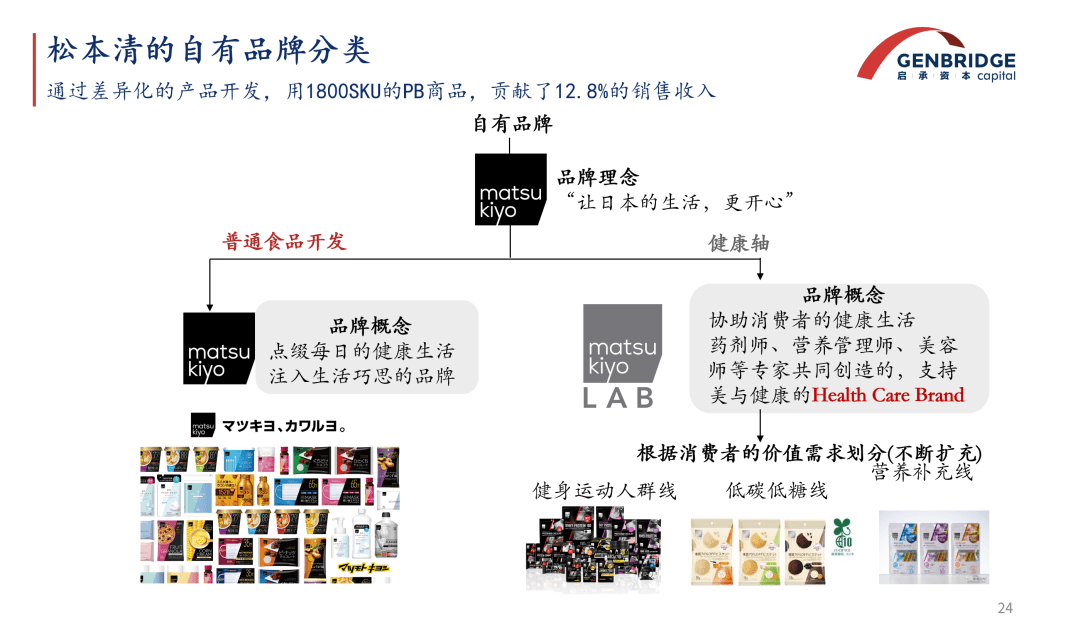

Similarly, Matsumoto Kiyoshi, a leading Japanese drugstore, addresses health and aging concerns through private-label products.

Consumers have more demand for physical healthcare against the backdrop of Japan's aging society. Traditional brands struggle to meet the increasing demand for healthcare solutions in an aging society. By collaborating with pharmacists, nutritionists, and beauty experts, Matsumoto Kiyoshi develops targeted products for fitness enthusiasts and other specific groups. Once consumers trust these products, they can be further customized to address specific pain points, achieving differentiation from regular brands. Currently, private-label products contribute 12.8% of Matsumoto Kiyoshi’s total sales.

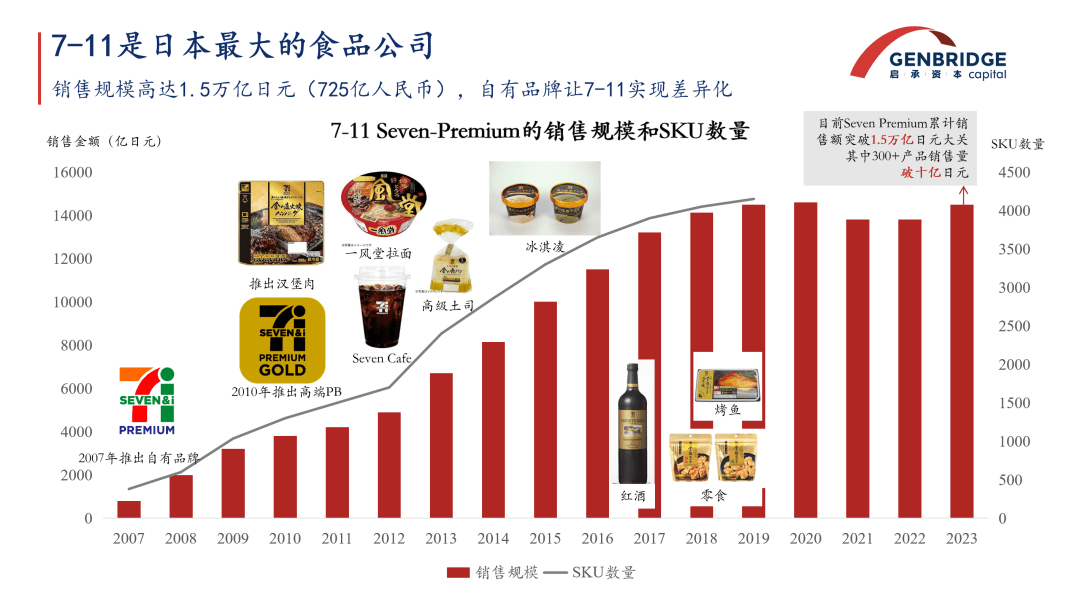

Initially underestimated, convenience stores in Japan have grown rapidly from 6,300 stores in 1983 to 58,000 stores in 2020, making them the dominant retail format. Their average daily sales per store have also increased from ¥300,000 to ¥500,000.

The key to their success lies in reverse product development based on consumer needs, continuously introducing new categories to cater to evolving demands.

- The introduction of desserts attracted more female customers.

- The addition of Oden (hot pot) and steamed buns provided seasonal and hot food options.

- Even sandwich textures were improved by working closely with upstream suppliers, pushing innovations in bread production.

As a result, 7-Eleven has become Japan’s largest food company, ranking first in private-label food sales. This was achieved through close collaboration with suppliers, ensuring continuous product innovation.

Recently, due to a decline in commercial zone populations, Japan’s small-format stores have been shifting toward hybrid retail models to enhance their appeal. Retailers are constantly exploring how to optimize product combinations to encourage one-stop shopping.

For example:

- Convenience stores have started expanding their store size. The new 7-Eleven store format is twice the size of the standard store and now sells fresh meat and vegetables.

- Drugstores have begun adding food categories. At Cosmo Drug, 60% of revenue now comes from food sales.

This trend closely mirrors developments in China’s retail market today.

Structural changes in China’s retail industry—not just a present phenomenon

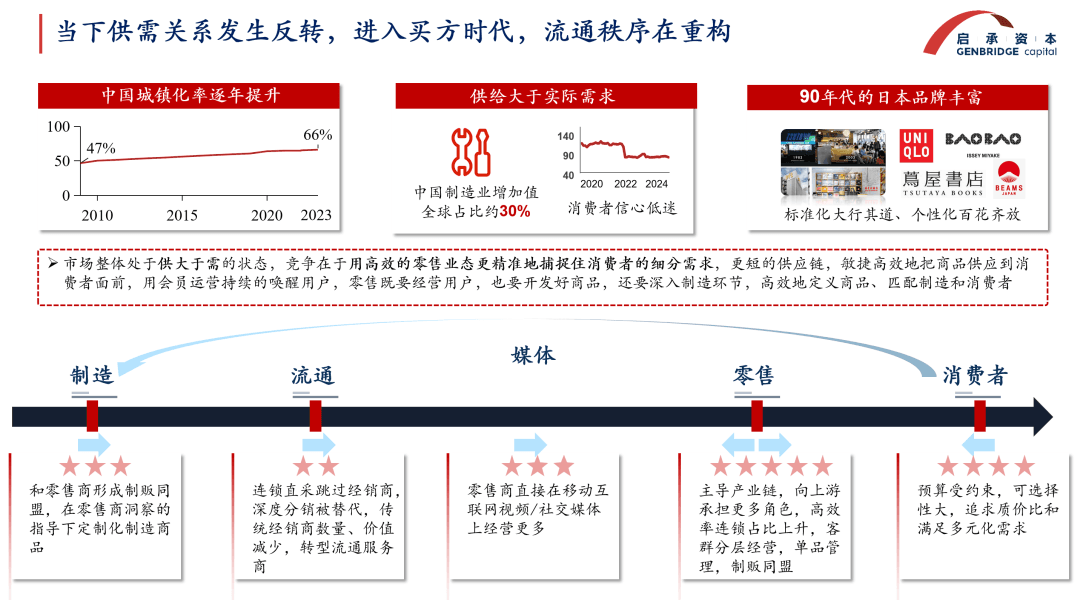

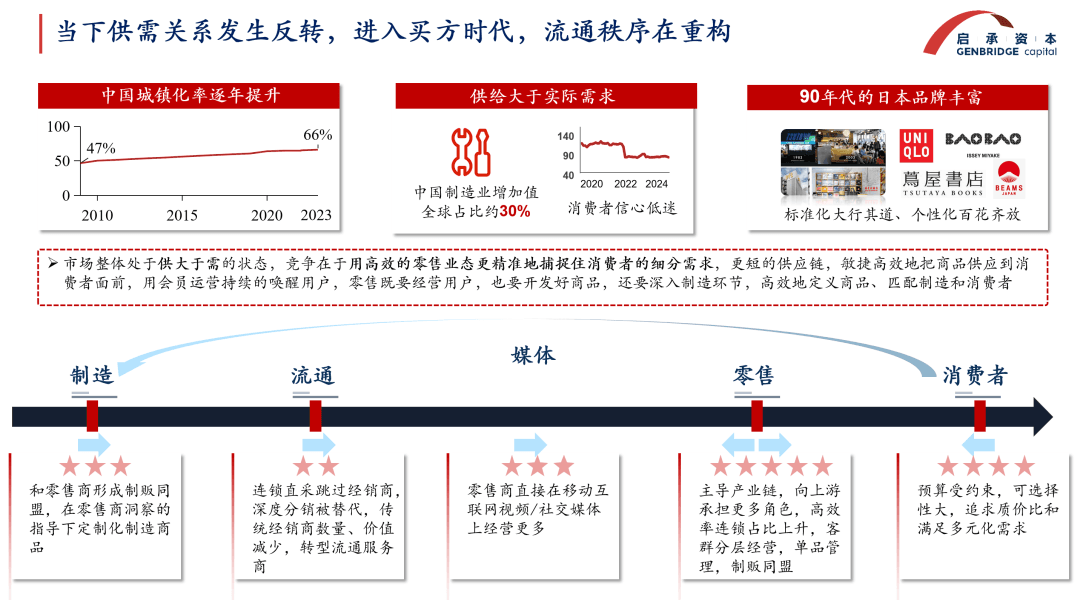

We are at a historical turning point. China’s retail industry is undergoing a generational transformation, and the order of consumer goods distribution is being reshaped.

In the past, the supermarket model entered China in the 1990s, first with Carrefour and then Walmart, shaping a 30-year period of prosperity in the country’s product distribution system.

This system was brand-driven, with retailers providing physical locations, while traditional centralized media like television facilitated consumer outreach, supported by a vast network of distributors. It was a classic seller’s market—supply was scarce, and as long as a product could be manufactured and delivered to consumers, it would sell without difficulty.

Companies like Yili, Nongfu Spring, and Master Kong became leading food brands in China primarily by establishing robust distribution networks that reached even county-level markets. At the time, large-scale flagship products dominated distribution channels, leaving little room for product diversification.

Today, however, China’s urbanization, supply chain maturity, and the rise of the internet—enabling more efficient and decentralized information dissemination—have led to an oversupplied market. China has transitioned from a seller’s market to a buyer’s market, where consumers now hold the decision-making power.

Retailers, being closest to consumers, are now taking on new roles in reshaping the entire supply chain.

For instance, Yan Jin Pu Zi partnered with Snack Is Busy to co-develop products that better align with consumer needs. As a result, this single channel now contributes over 10% of Yan Jin Pu Zi’s sales, while also enhancing its competitiveness across other retail channels.

Retailers are also bypassing traditional distributors to act directly as consumer representatives. New Joy Mart, for example, collaborates directly with factories, enabling them to produce high-quality private-label products in a short time frame.

In the buyer's market under the generational change in food retailing, we clearly see several of these themes:

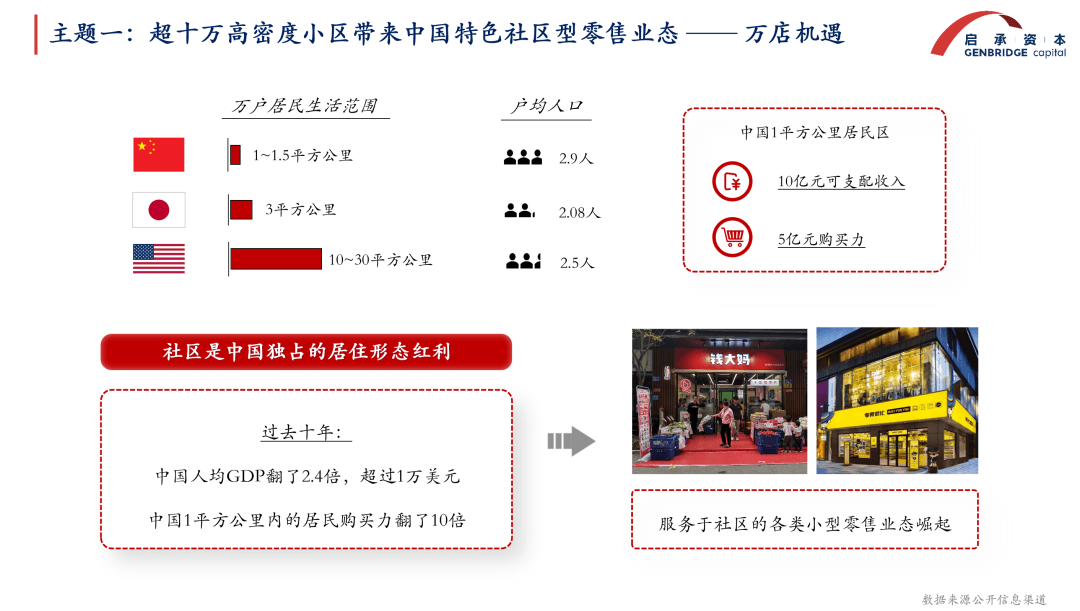

- Community-Centric Retail

China’s urban development accelerated before 2010, and by 2015, occupancy rates in newly built communities had increased, officially ushering in the era of community-based retail.

Unlike Japan and the U.S., where commercial districts are more spread out, China’s high-density residential communities create unique retail conditions:

China: 1–1.5 km² per 10,000 households

Japan: 3 km² per 10,000 households

U.S.: 10–30 km² per 10,000 households

In this compact environment, a 1 km² area can generate ¥500 million in purchasing power. Capturing just 1% of this market (~¥5 million) is enough to sustain a small-format retail store. This has fueled the rapid rise of community-focused retail chains such as Snack Is Busy, Qian Da Ma, and New Joy Mart.

- The Rise of Discount Retail

Discount retail is an effective competitive strategy in China, fundamentally driven by supply chain optimization. Traditional supermarkets have many inefficiencies, and retailers are addressing these pain points to enhance value for consumers.

For example, New Joy Mart has streamlined its fresh milk supply chain by integrating cold chain logistics, significantly reducing distribution costs and passing the savings on to consumers.

- The "Manufacturing-Retail Alliance"

Previously, retailers and suppliers had a transactional relationship, with retailers selling products and suppliers producing them. Today, however, retailers are increasingly collaborating with manufacturers, forming a "manufacturing-retail alliance" where retailers not only understand manufacturing but also help optimize products.

如山姆、零食很忙、新佳宜等都会扶持单品工厂进行产品开发。启承也曾组织钱大妈、新佳宜等与相关企业参加产业机会研讨会,旨在构建长期的伙伴关系。

Retailers like Sam’s Club, Snack Is Busy, and New Joy Mart are actively supporting specialized manufacturers in product development. GenBridge Capital has even organized industry forums, bringing together chains like Qian Da Ma and New Joy Mart with relevant businesses to foster long-term partnerships.

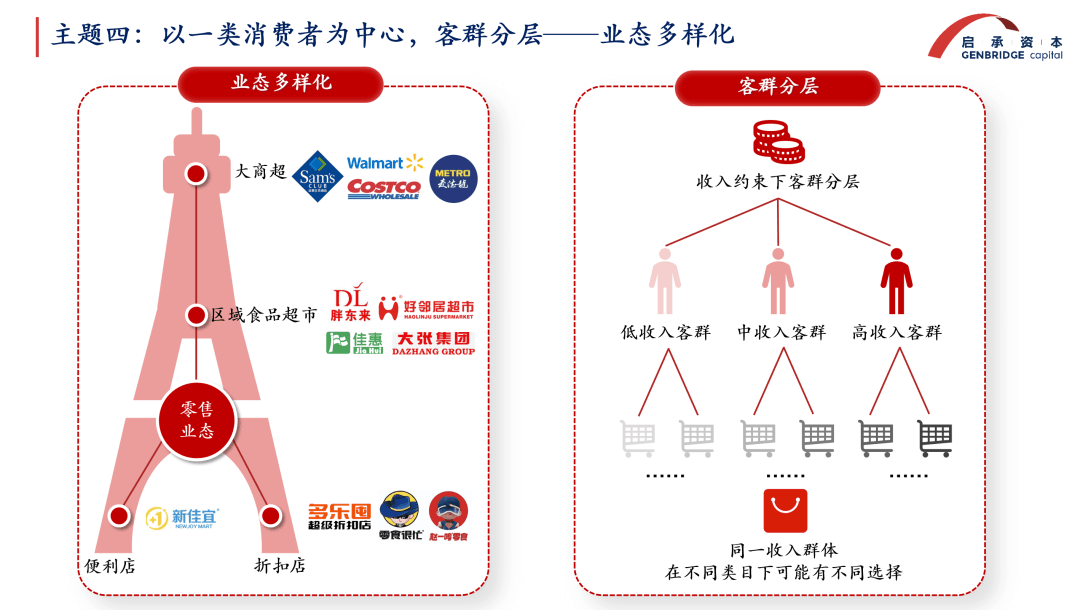

- Market Segmentation & Retail Format Diversification

Traditional supermarkets aimed to serve a broad national audience with uniform offerings. However, no single retail format can dominate the market anymore—each must cater to a specific consumer segment to succeed.

For example:

- Sam’s Club thrives by targeting urban middle-class consumers.

- Pang Dong Lai focuses on third-tier cities in Henan, serving mass-market customers.

- Duo Le Tun succeeds in Zhengzhou, catering to lower-income groups.

- Beyond Price Wars—Creating New Value

Retail competition should not be reduced to mere price wars; instead, value creation is key. This includes:

- Emotional value (e.g., brand storytelling)

- On-site production value (e.g., fresh food prepared in-store)

- Experiential value (e.g., interactive retail experiences)

Over the next decade, China’s ¥10 trillion retail market will undergo a significant shakeout.Today, China has nearly 6 million offline stores, with food and grocery stores being the most common. As high-efficiency retail models continue to replace low-efficiency formats, we may see the gradual consolidation of various store types—including hypermarkets, supermarkets, convenience stores, and mom-and-pop shops—into four broad categories:

- Super large-scale retailers

- Large-scale retailers

- Medium-scale retailers

- Small-scale retailers

Some regional retailers, like Pang Dong Lai, will continue to grow stronger. Nationwide, there are currently few retail companies surpassing ¥2 billion in revenue, but industry leaders will consolidate their dominance. At the same time, there remain vast opportunities for new retail chains to scale up to 10,000 stores and ¥10 billion in revenue.

Combined with successful overseas experience, China’s retail market still holds tremendous opportunities for those who combine capital strength with industry expertise.

For instance:

- Canada’s ACT Group started with just a handful of convenience stores but expanded through 33 acquisitions to 16,700+ stores, reaching a market value of CAD 73.6 billion. It recently made a buyout offer for Japan’s 7-Eleven.

- H-E-B, a regional grocery chain in Texas, operates 400+ stores but has achieved $43.6 billion in revenue.

Conclusion

Over the past two decades, China’s retail industry has experienced waves of change, from offline to online transformation. Qicheng Capital has been deeply involved in this evolution—studying global retail giants like Amazon, Walmart, Costco, and 7-Eleven, and developing its own retail investment methodology.

GenBridge is not just an observer or researcher but an active participant in retail transformation.

Since its founding in 2016, Qicheng has focused on investing in China’s new-generation brands and retail chains, backing 20+ companies with a combined 30,000+ stores.

Retail may seem unpredictable, but its underlying logic remains clear:

- Retail is always a high-efficiency industry.

- High-efficiency models will continuously replace low-efficiency formats.

- Survival depends on adapting to structural changes in consumer demand.

As traditional supermarkets and hypermarkets decline, new retail formats like Snack Is Busy and New Joy Mart are thriving.

With China’s retail industry fully entering the buyer’s market era, the transformation of retail chains is now unstoppable. As the closest intermediaries to consumers, retailers will play an increasingly central role in reshaping the entire supply chain.