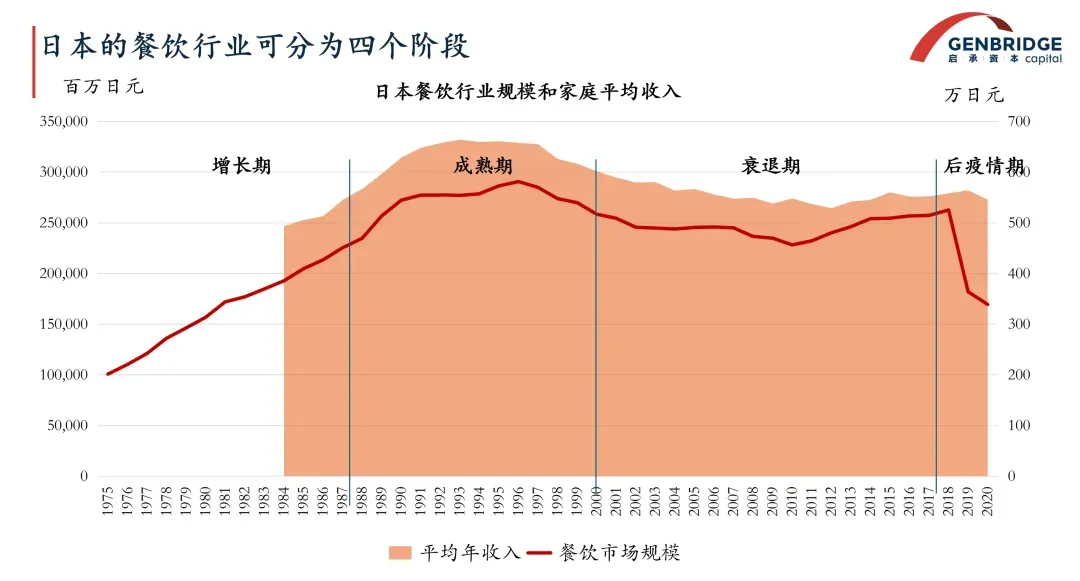

Over the past 30 years, the development of Japan’s F&B industry has been closely linked to changes in per capita annual income.

Since the 1980s, the scale of the F&B industry has shown high sensitivity to fluctuations in overall income levels. However, starting from the late 1990s, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, the industry has shown a clear trend of overall decline.

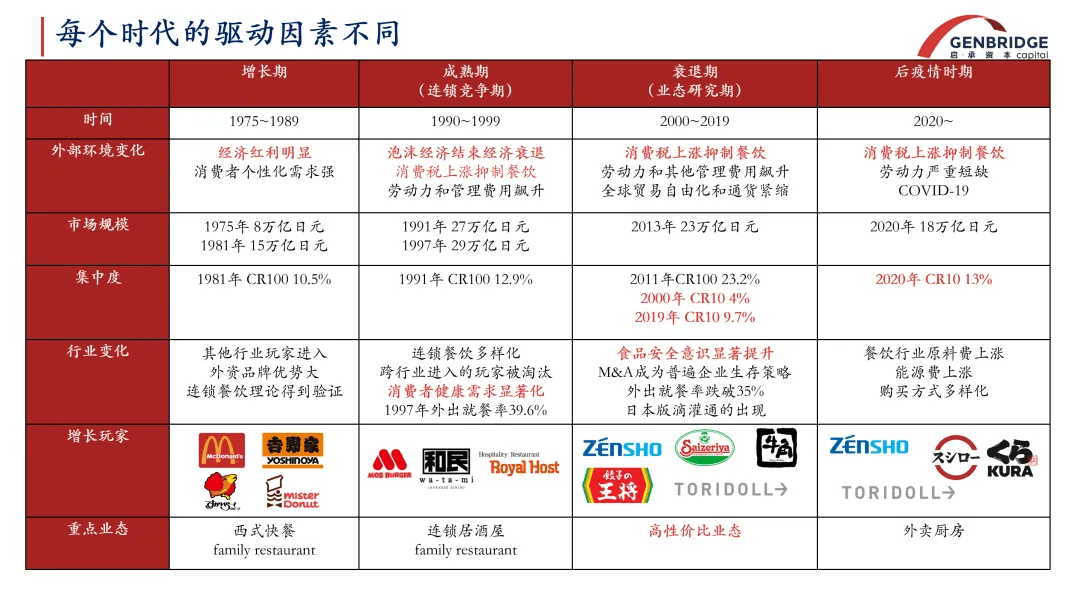

From chain expansion to industry consolidation, Japan's F&B sector has undergone a series of transformations. The CR100 (concentration ratio of the top 100 companies) rose from 10.5% in 1981 to 23.2% in 2011. Within that, the CR10 (top 10 companies) grew from 4% in 2000 to 13% in 2020, indicating a trend toward concentration around leading enterprises.

The challenges companies face vary with changes in the external environment. During growth phases, businesses focus on expansion and opening new locations (similar to the current situation in China). During maturity phases, rising costs and declining consumer purchasing power become main issues.

Moreover, Japan’s consumption tax policy has also impacted the F&B industry, causing a general price increase of around 10% for goods and services. Due to high sensitivity to price changes, companies have been forced to adopt cost-reduction and efficiency-improvement strategies in response to tax hikes.

Since 2000, improving operational efficiency and reducing costs has become a critical strategy for F&B businesses. At the same time, the industry has been undergoing intense changes.

On one hand, there have been frequent mergers and acquisitions—"big fish eating small fish" and alliances between strong players. New business models have also emerged, such as Japan’s version of “Drip Capital,” called Venture Link, which has promoted more specialized development within the chain restaurant industry, successfully creating over 20 chain brands, 10 of which have gone public.

On the other hand, consumer habits have changed significantly. The proportion of people dining out over the course of a year has steadily declined and may have fallen below 30% in recent years. Fresh food sold through retail channels has partially replaced the demand for dining out.

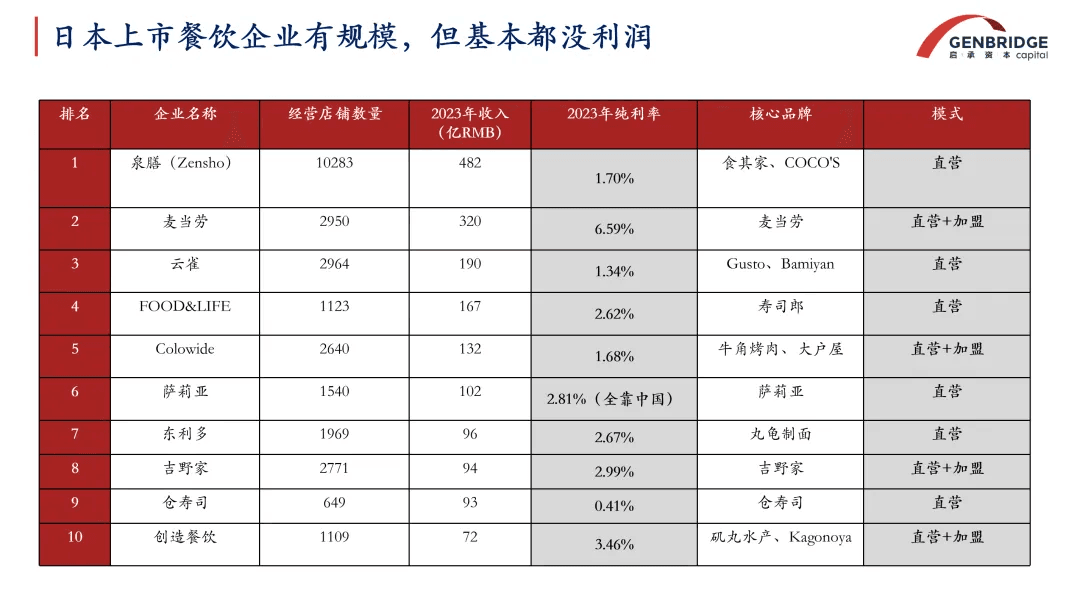

In addition, Japan’s F&B sector faces a major issue—despite its large scale, profit margins are extremely low. During periods of economic deflation, businesses dare not raise prices and often have to lower them, even as costs for utilities, labor, rent, and raw ingredients continue to rise. The depreciation of the yen has posed a particularly tough challenge for Japanese companies. Under the dual pressure of being unable to raise prices and facing rising costs, profit margins in the industry remain very slim.

For example, while Saizeriya may appear successful, its profits have mainly come from the Chinese market in recent years, nearly all its profits were generated from China in 2023.

Furthermore, some Japanese F&B companies, despite their razor-thin margins, are still able to stay afloat largely due to extremely low capital costs. When capital costs are low enough, even unprofitable businesses can continue operating through low-interest loans, as capital becomes virtually free and banks also face pressure on lending.

In this market environment, F&B companies are being forced to reconsider several key questions:

- How can a business survive when consumer spending is shrinking and costs are rising?

- What kinds of “unexpected” competition does the Japanese F&B industry face?

- How can companies achieve differentiated innovation?

- What forces could reshape the industry? And which pitfalls should be avoided?

High cost-performance ratio as a core competency for the future

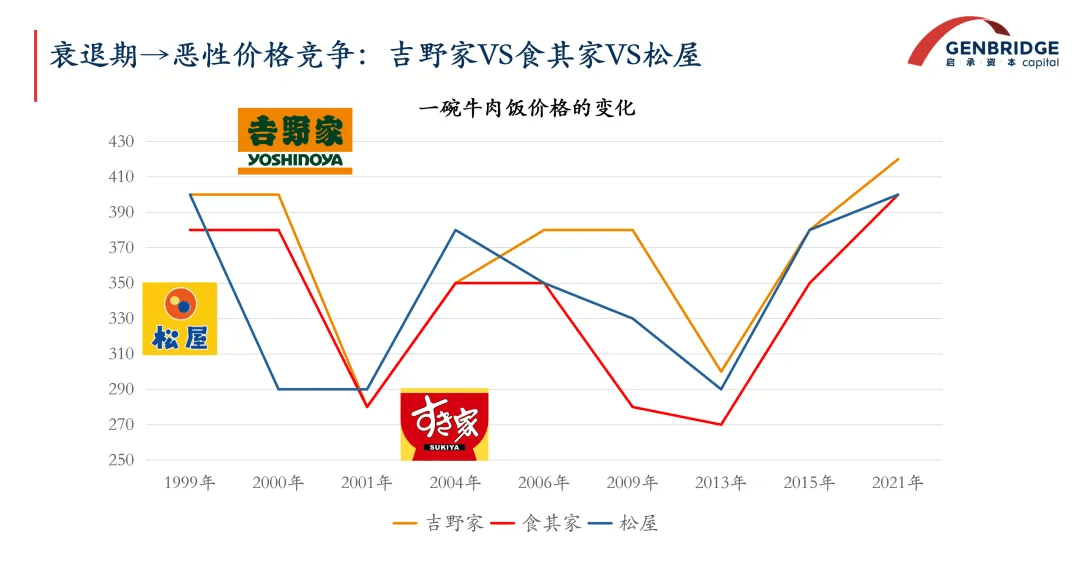

In 2002, McDonald’s launched a price war in Japan by introducing a weekday half-price strategy. This approach halved the price of key menu items—for example, burgers dropped from 130 yen to 65 yen. In effect, McDonald’s began doing what China’s Tastien does today.

McDonald’s low-price strategy started in 2002 and continued at least until 2008. Although there were some later adjustments, low pricing remained the norm. This move triggered a widespread price war across Japan’s food and beverage industry.

Following McDonald’s lead, the beef bowl industry also joined the price battle. In 1996, a bowl of beef rice cost around 400 yen (approximately 30 RMB at the exchange rate then). Later, major beef bowl brands entered into sustained price competition. These companies were extremely sensitive to pricing, staying closely aligned with one another—no one dared to raise prices. The competition was so intense that even a difference of 10 yen (just a few cents) could influence consumer choices. Over a span of two years, beef bowl prices dropped from 400 yen to 290 yen—a reduction of 30% to 40%.

In Japan’s F&B industry, labor costs make up a relatively high portion of total expenses—around 20% to 25%—which is higher than the corresponding ratio in China. To control costs, companies often optimize by adjusting staff numbers and increasing the proportion of part-time workers.

Saizeriya is one of the best examples of cost control. Its core strategy revolves around continuous improvements in both supply chain and store operations. On one hand, it enhances customization levels; on the other, it streamlines in-store procedures to improve operational efficiency.

Take Saizeriya’s pasta as an example. They’ve evolved from using dry and frozen pasta to pre-prepared varieties, reducing cooking time and simplifying preparation steps. This also decreases equipment needs and frees up more space at the table.

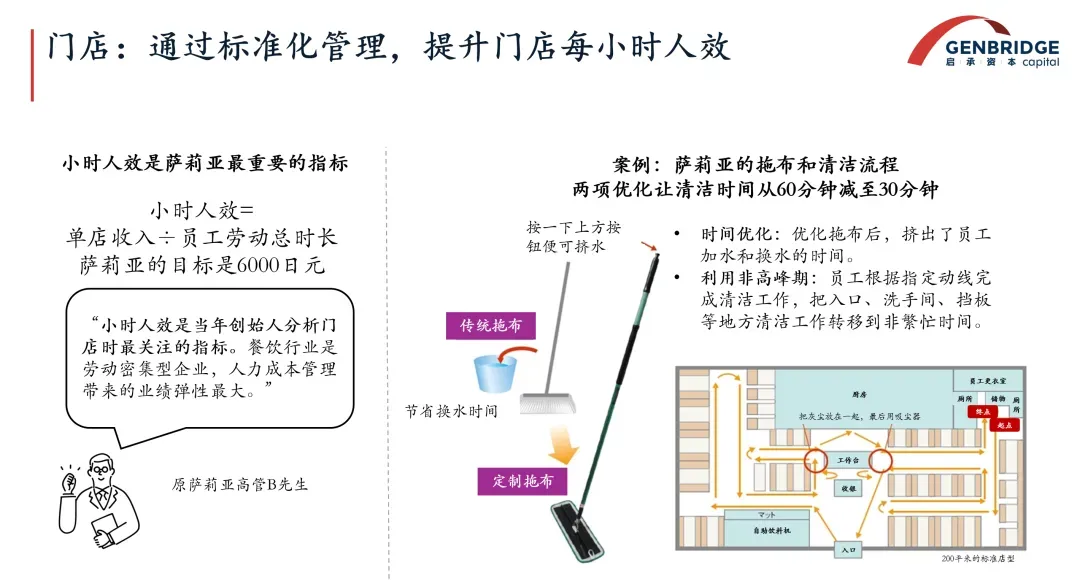

In daily operations, Saizeriya places great emphasis on per-hour labor productivity—that is, how much each employee contributes to total store sales per hour. As a labor-intensive industry, this is a key focus in F&B. Even for routine tasks like mopping floors, Saizeriya employs custom tools and procedures to maximize efficiency. Through specialized mops and clearly defined cleaning sequences, the company aims to reduce labor time and boost store productivity.

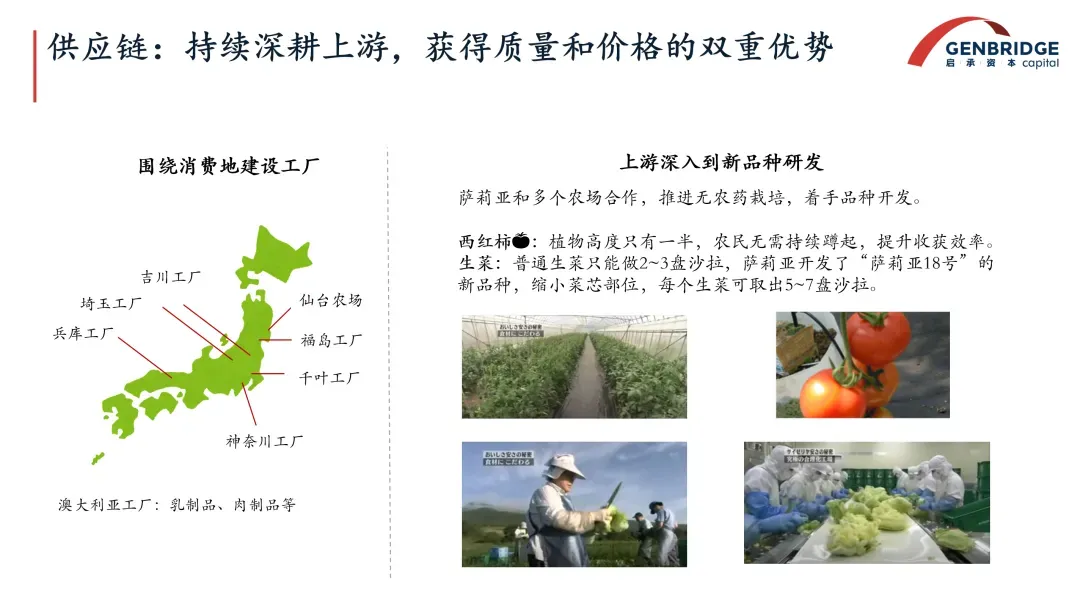

On the supply chain side, Saizeriya took further steps to control costs by building its own factory in Australia, where it produces meat sauces and baked rice. These are frozen and shipped to stores for defrosting and preparation, creating a vertically integrated supply chain model similar to that of retail giants.

Saizeriya has also invested in product development. For instance, it developed a new variety of tomato plant that grows to only half the height of a regular plant—reducing the labor and time required for harvesting. These accumulated efficiencies have enabled Saizeriya to operate with high productivity. The company has also built several central kitchens and factories to support its production and supply chain needs.

The erosion of foodservice by fresh food retail

Beyond the intense price competition within the foodservice industry itself, the growing trend of fresh food retail is further encroaching on traditional restaurants. Convenience stores that sell ready-to-eat fresh food have become one of the biggest competitors to the dining-out sector.

In Japan, the taste and quality of food offerings at convenience stores vary by region, and their product update cycles are sometimes even faster than those of restaurant chains, marking a phase of intense competition. For example, at 7-Eleven, approximately 70% of SKUs are region-specific, while 30% are offered nationwide—demonstrating a high level of regional customization.

In terms of overall scale, the prepared meal market in Japan exceeds 700 billion RMB, with the majority of it being channel-driven: convenience stores, supermarkets, and other retail outlets contribute over 300 billion in prepared foods alone.

As fresh food offerings in retail channels like convenience stores and supermarkets become increasingly abundant, “middle meals” (ready-to-eat food not consumed on-site) are rapidly gaining popularity in Japan.

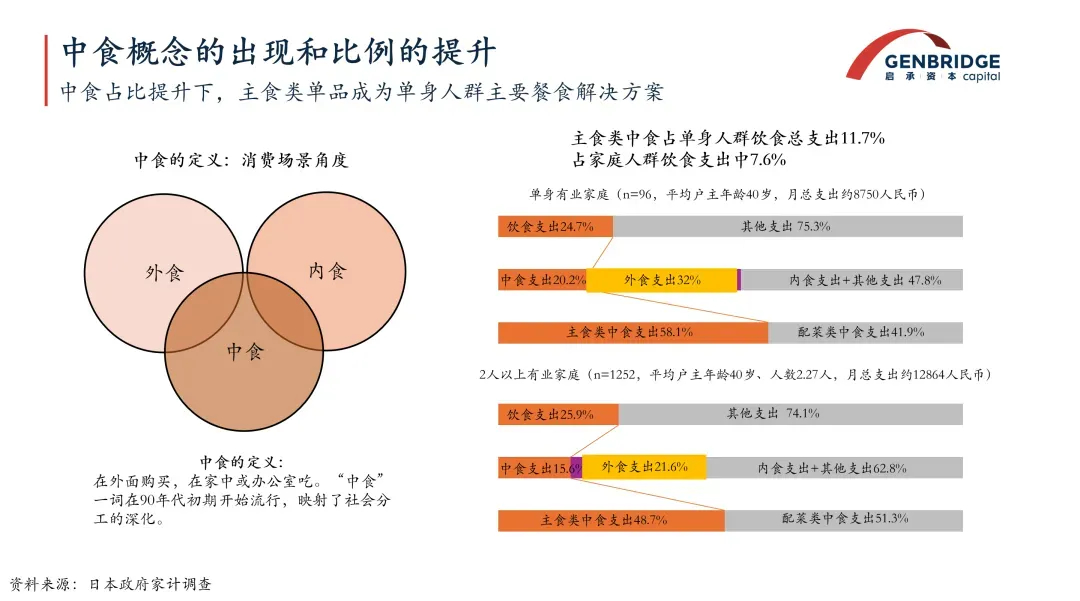

Japan’s offline dining consumption scenarios are typically divided into three main categories:

- Soto-shoku (eating out)

- Nai-shoku (cooking at home)

- Naka-shoku (purchasing food to eat at home or at the office—between eating out and cooking)

Among single-person households, naka-shoku accounts for about 20% of total food expenditure, and about 15% for households with two or more members, indicating its substantial share in Japan’s overall food consumption.

The rise of naka-shoku is driven by structural factors on both the demand and supply sides.

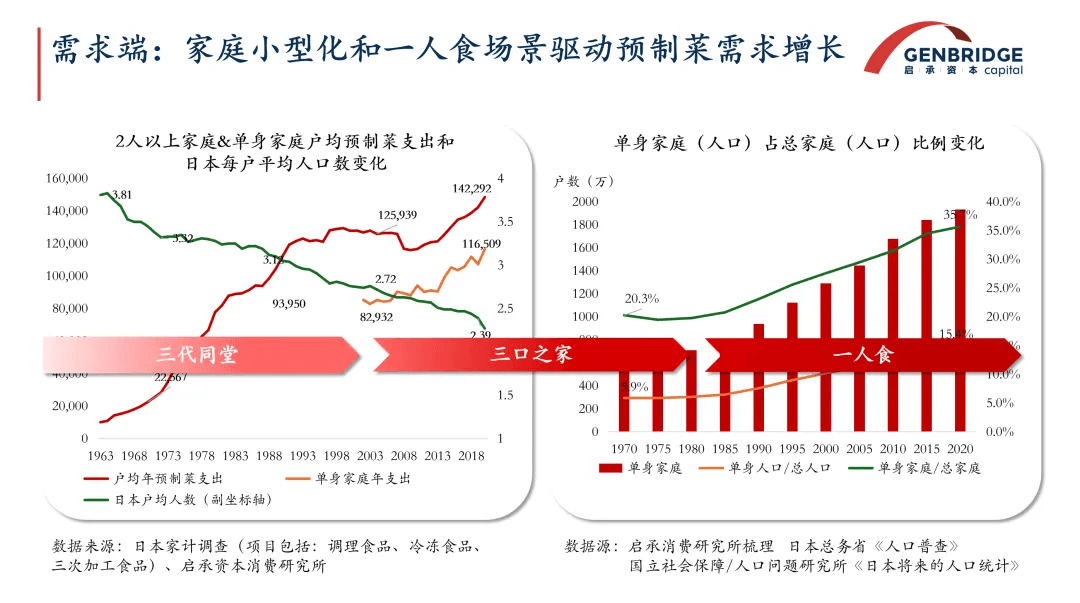

On the demand side, Japan’s average household size has been shrinking—from 3.8 people in earlier years to just 2.39 today. This trend toward smaller households has boosted the growth of the prepared meal market, essentially outsourcing cooking tasks to professional services. Notably, 35% of Japanese households are single-person households, which form the core consumer base for prepared meals.

This is especially evident among white-collar workers, whose lifestyles have changed significantly during periods of economic stagnation. Data shows that the average lunch spending by white-collar workers has dropped from 700 yen to 500 yen, and lunch duration has also shortened significantly—from 33 minutes to 21 minutes. As a result, many consumers have stopped dining in restaurants and are instead seeking faster, more cost-effective lunch options, forcing the industry to adapt.

On the supply side, prepared meals have become a high-margin segment within Japan’s retail sector. Many companies are actively developing their prepared meal businesses. For supermarkets and convenience stores, prepared meals represent a key source of revenue and profit. In Japan, prepared meals may account for 10% of a convenience store’s revenue but contribute up to 15% of its profit. Furthermore, “daily delivered” fresh foods account for a large portion of sales, reaching as much as 33.5%.

Differentiation amid the pre-made food trend

Although Japan's frozen and pre-made food industry is highly developed, over-reliance on pre-made dishes can lead to a lack of differentiation, thereby impacting profits and growth. Businesses need to innovate on the foundation of standardization—this has been one of the most critical challenges for Japan's food and beverage industry over the past two decades.

So, how can the F&B industry maintain differentiation amid the pre-made food trend? Two examples are worth noting.

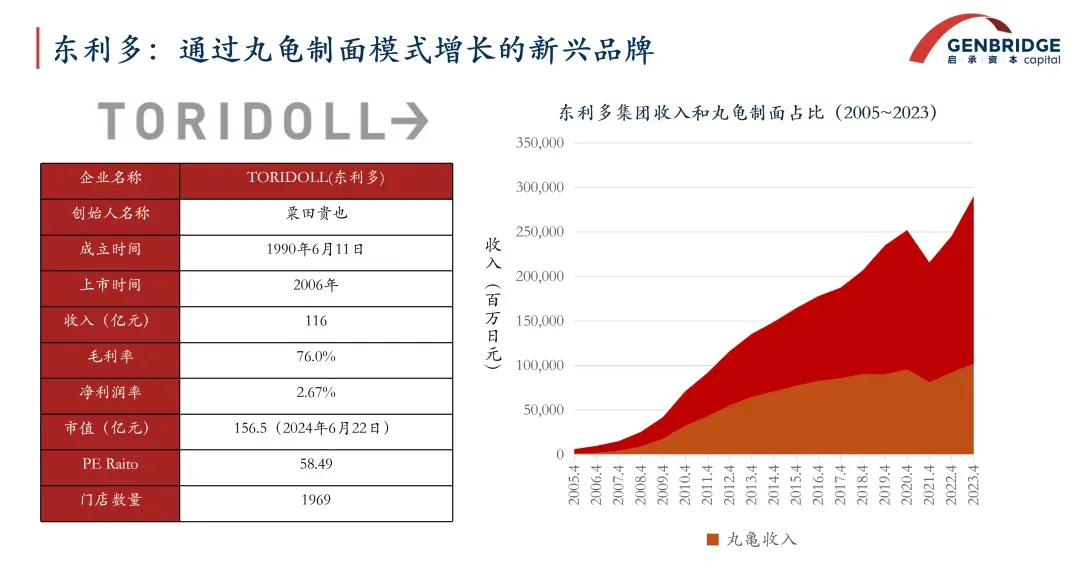

One is Toridoll Holdings, whose subsidiary brand "Marugame Seimen" began opening stores in 2002 and achieved revenues of 11.6 billion RMB over 20 years. In Japan, due to the lack of financial leverage and capital investment, opening stores typically requires using internal funds, making such growth exceptionally rapid. The company's market capitalization reached 15.6 billion RMB, with a P/E ratio as high as 60.

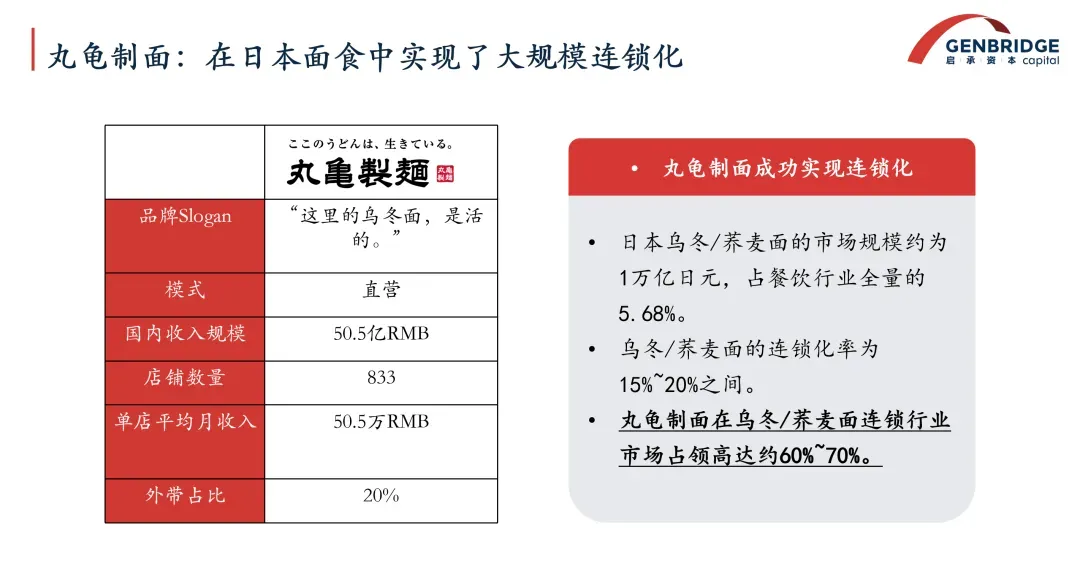

Toridoll's success is partly attributed to its flagship brand, "Marugame Seimen," which operates 833 directly-owned stores specializing in fresh, handcrafted udon noodles. This emphasis on freshness and on-site preparation has allowed the brand to maintain differentiation and competitiveness amid the pre-made food trend.

The company succeeded by establishing a large chain brand in Japan's udon market. Udon is a high-frequency, quick-consumption staple in Japan, with the average Japanese person eating it about once a week, each meal taking roughly five minutes.

The udon market is worth 1 trillion yen, but the chain penetration rate is only 15-20%. Yet, Toridoll holds 60-70% of the market share among chain udon brands.

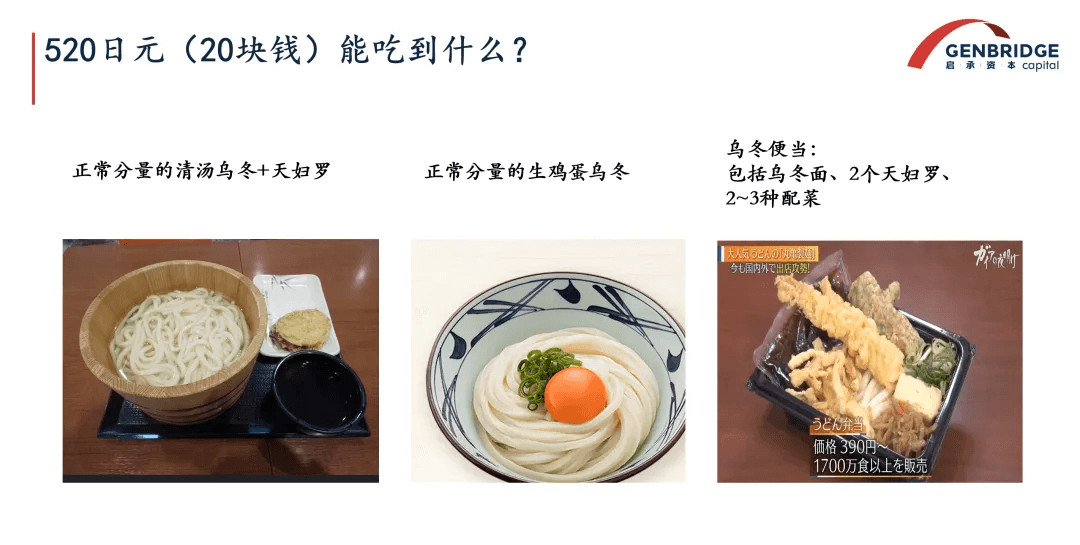

The company is known in Japan for its high cost-performance ratio, offering udon noodles that are both affordable and freshly made. Consumers can enjoy a bowl of udon for just over 20 RMB, or for 30-40 RMB, get udon with side dishes—making it a highly cost-effective option in Japan's F&B scene and providing consumers with a better dining experience.

The company is known in Japan for its high cost-performance ratio, offering udon noodles that are both affordable and freshly made. Consumers can enjoy a bowl of udon for just over 20 RMB, or for 30-40 RMB, get udon with side dishes—making it a highly cost-effective option in Japan's F&B scene and providing consumers with a better dining experience.

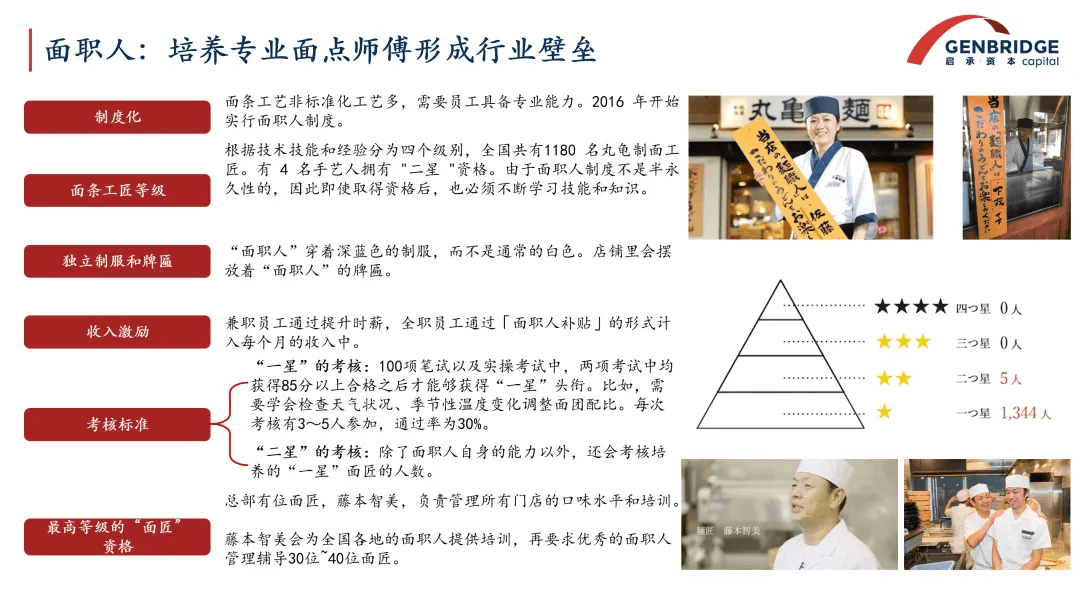

Building on its freshly made concept, the brand makes consumers feel they are enjoying not pre-made dishes, but fresh noodles crafted right before their eyes by skilled artisans. This stems from the company’s emphasis on backend staff training, establishing a system of certified "udon craftsmen" who undergo rigorous testing and incentive programs to enhance frontline employees' professional skills.

Japanese companies often maintain low management costs partly because 80% of their workforce consists of part-time employees. These workers efficiently handle food preparation while remaining highly compliant with management—a model that forms one of the company’s core competitive advantages.

Another key role in the company is the "Master Udon Artisan," who continuously trains frontline staff through various methods. Udon-making is a skill with inherent challenges, as it requires adjustments based on factors like weather, humidity, air pressure, and environment to ensure consistent noodle texture and quality. This meticulous attention to detail and ongoing skill development are critical factors behind the company’s success.

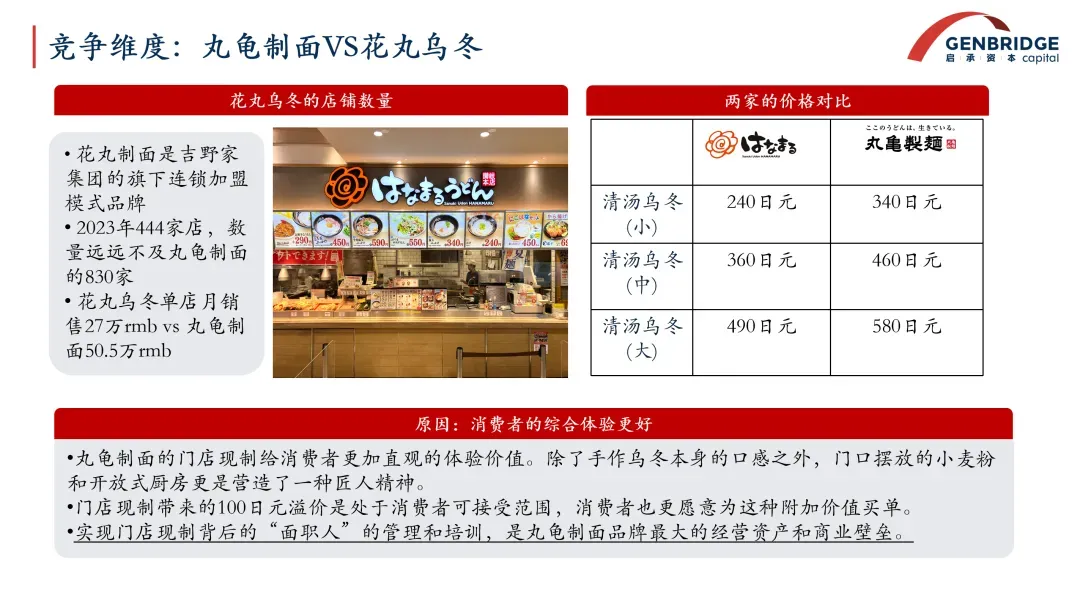

Facing competition from rivals like "Hanamaru Udon," which achieved rapid growth by setting up industrial-scale factories and undercutting "Marugame Seimen" by 100 yen (roughly 5-7 RMB) per meal, the company still holds its ground. Data shows that consumers are willing to pay slightly more—say, an extra 5 RMB—for a meal that delivers a greater sense of value and a better dining experience.

In 2023, "Hanamaru Udon" operated 444 stores, while "Marugame Seimen" had 830, with a significant gap in both store count and per-store performance. "Marugame Seimen" achieved a monthly revenue of 500,000 RMB per store, compared to "Hanamaru Udon's" 270,000 RMB.

Amid the pre-made food trend, a non-pre-made strategy has become a core method for differentiation. For instance, "Marugame Seimen" maintains high gross margins by offering cost-effective udon—top-performing stores achieve a 50% gross margin and around 40% net profit margin.

In China, many noodle restaurants emphasize in-house fermentation and handmade noodles. For example, Ma Jiyong Noodle House highlights its on-site noodle preparation through open kitchens, allowing customers to witness the process as part of its branding.

Another case is Mos Burger, a mid-to-high-end Japanese burger chain with 1,700 directly operated stores and annual revenue of approximately 4 billion RMB.

Its differentiation lies in its in-store preparation, which is less reliant on pre-made ingredients compared to McDonald's, enhancing its premium positioning with prices about 20% higher.

In the 1990s, Mos Burger faced growth bottlenecks—its reliance on fresh preparation led to inefficiency and potential customer dissatisfaction. It then pivoted strategically by emphasizing health, adopting organic vegetables as a key ingredient, and rebranding with a green logo to distinguish its burgers. The company established stable partnerships with upstream farms for organic cultivation and prominently displays the origin of daily vegetable supplies in stores, reinforcing its value and quality to consumers.

In Japan, organic vegetables typically cost 30% more than conventional ones, not only due to farming methods but also strict environmental controls during cold-chain transportation to ensure freshness.

By leveraging organic vegetables as a strategic ingredient, Mos Burger carved out its differentiation. In Japan's F&B industry, where pre-made food has become a baseline capability, brands must identify strategic ingredients to sustain competitiveness—a lesson Chinese companies should carefully consider.

Even giants stumble: lessons from Japan's cost-cutting obsession

In their relentless pursuit of cost efficiency, Japan's F&B giants have left behind cautionary tales. Here are two typical cases:

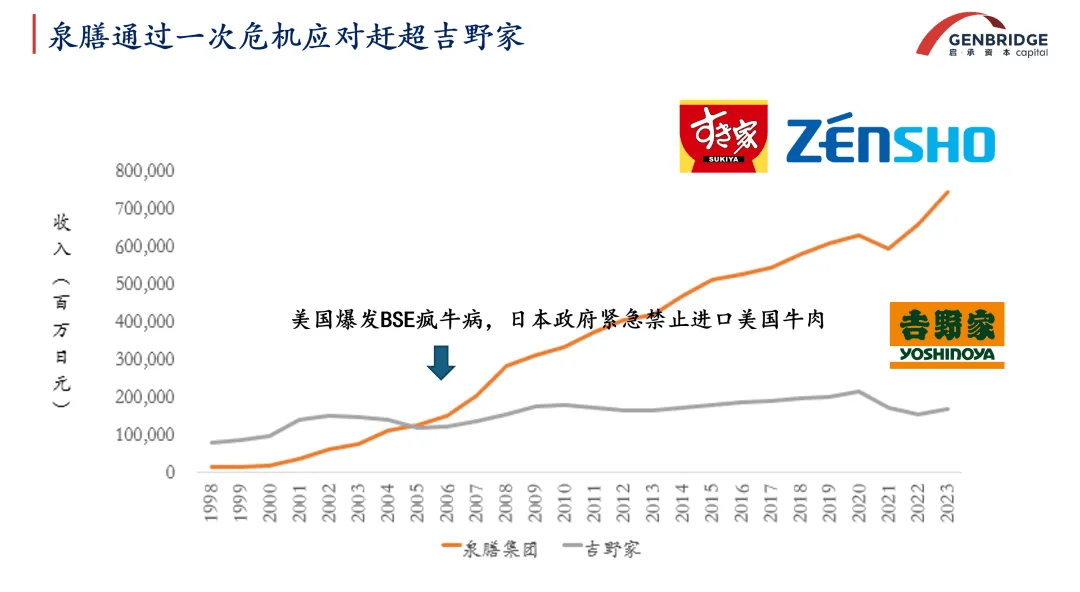

The first case is the story of how Izusen overtook Yoshinoya. The founder of Izusen was a former Yoshinoya employee. Dissatisfied with the company, he decided to start his own business, establishing Izusen Co. and the Sukiya brand.

The turning point that allowed Izusen to surpass Yoshinoya occurred between 2003 and 2006, when the outbreak of mad cow disease in the United States led Japan to ban the import of American beef. This had a major impact on Japanese beef bowl chains that relied on U.S. beef. Against this backdrop, the two companies made very different decisions.

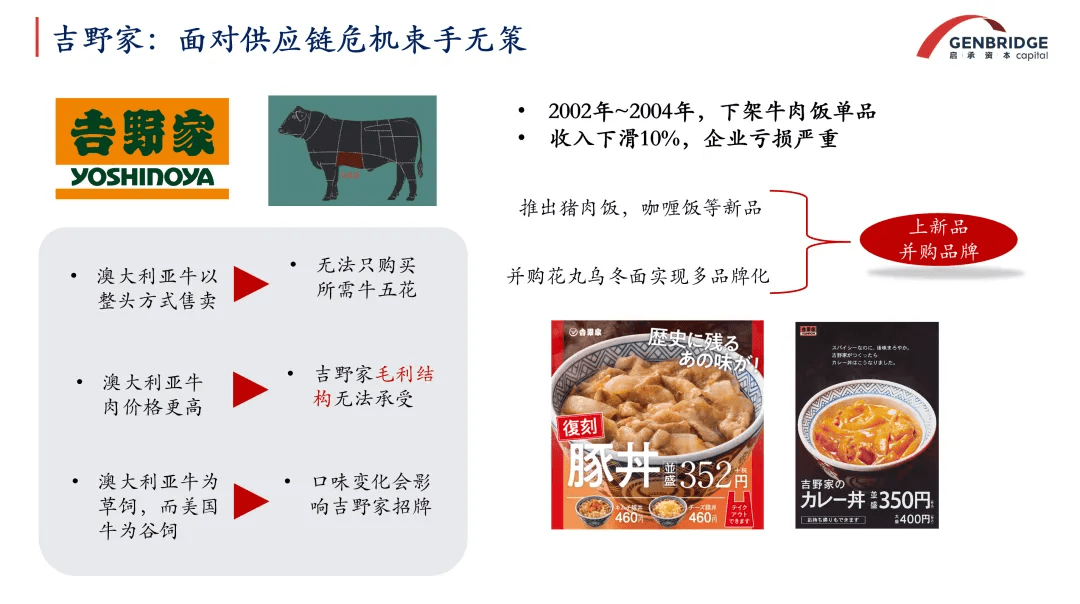

Yoshinoya primarily used U.S. beef, specifically the short plate cut. However, Australian beef was sold by the whole cow, which meant many cattle were needed to gather enough short plate, limiting supply. Additionally, Australian beef was more expensive at the time. Yoshinoya already operated on a low gross margin (59.8%) and couldn’t absorb the rising costs. Furthermore, Australian beef was grass-fed, resulting in a different flavor from the grain-fed American beef, which Yoshinoya feared would harm its brand image.

Taking all this into account, Yoshinoya decided to remove beef bowls from its menu, leading to a 10% drop in revenue and severe losses. To cope with the crisis, Yoshinoya shifted focus to other products, such as acquiring the Hanamaru udon brand and launching new items like pork bowls and curry rice.

Sukiya, under Izusen, took a different path. They used Australian beef as a substitute and adopted a multi-brand sourcing strategy to make use of the entire cow, catering to a broader range of customers and dining scenarios. Sukiya also had a higher gross margin (66.9%), allowing it to raise prices and expand the product lineup (e.g., offering more toppings) to attract consumers despite increased costs. In response to the flavor difference of Australian beef, Sukiya adjusted its recipe, using toppings to mask the flavor change.

As a result, Sukiya managed to reintroduce its beef bowls within six months. During that time, as no other beef bowls were available in the market, Sukiya raised its price from 280 yen to 380 yen. While Yoshinoya was still scrambling for solutions, Sukiya had already taken off. This was a critical moment in Izusen's rise over Yoshinoya.

After this event, Izusen further strengthened its upstream supply chain management. For example, they established a food research lab to study how to improve the taste and preparation of ingredients. They also decentralized procurement authority and enhanced safety mechanisms, facilitating the company’s transformation and upgrade.

The second story is about McDonald's.

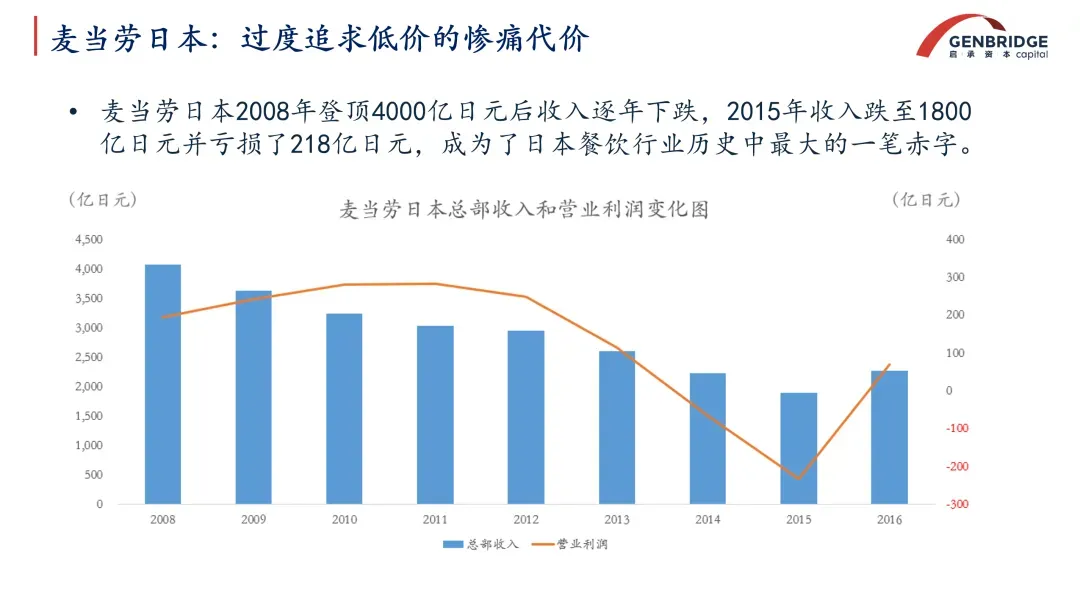

McDonald’s became the biggest loss-maker in the history of Japan’s food service industry. Its revenue in Japan plummeted from 400 billion yen in 2008 to 180 billion yen in 2015, with losses reaching 21.8 billion yen (about 1 billion RMB).

Initially, Fujita brought McDonald’s to Japan with a focus on direct ownership and customer service. But in 2005, McDonald’s Japan underwent a leadership change. Eikoh Harada, then CEO of Apple Japan, joined McDonald’s and brought an American-style management approach. He implemented a 24-hour operation strategy, which increased revenue but didn’t improve profits.

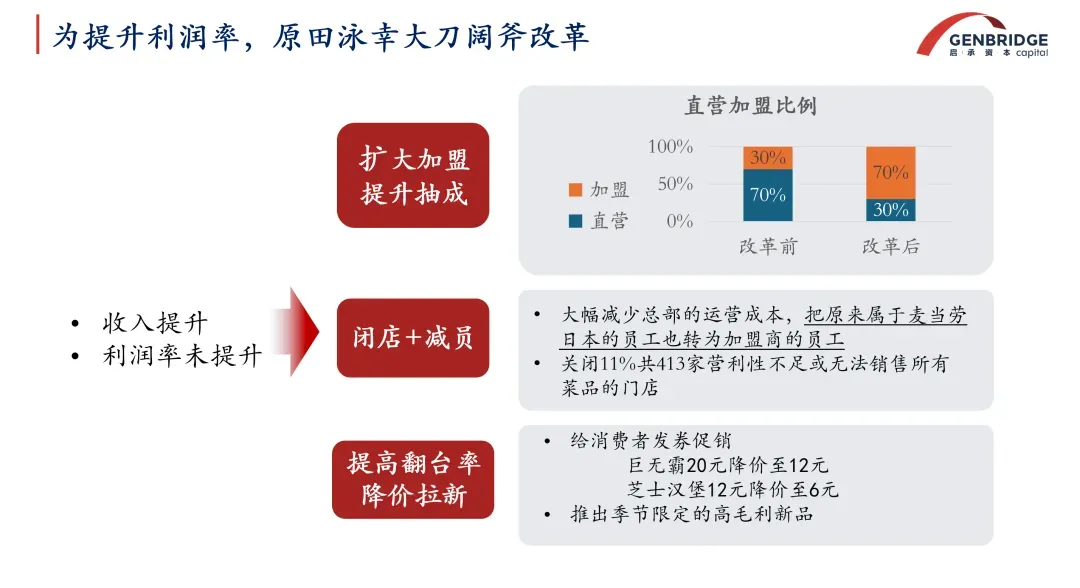

Under pressure to boost profits, the Japanese CEO introduced several reforms:

- First, he shifted the business model from 70% company-owned and 30% franchised to a franchise-dominant model, transferring costs to franchisees.

- Second, he cut staff to improve efficiency, transferring McDonald’s Japan head office employees to franchise stores to reduce head office expenses.

- Third, he focused on aggressive price-cutting promotions, like discount coupons—dropping the Big Mac price from 20 to 12 yen, and cheeseburgers from 12 to 6 yen—while also launching high-margin new products to increase table turnover.

These reforms temporarily improved McDonald’s performance in Japan. However, in 2014, a food safety scandal caused a sharp loss of customer trust, staff resignations, and damage to the brand’s image.

In fact, the growth masked underlying contradictions. To increase franchise fees, McDonald’s Japan adopted a hardline approach to communication, pressuring company-owned stores to switch to franchising. This led to management and communication issues. Many veteran employees were unhappy with the new strategies, causing staff turnover in stores and across the supply chain.

The 24-hour operation and ultra-low price strategy attracted many customers outside McDonald’s target demographic, resulting in messy, poorly maintained stores. This drove away the core family customers willing to pay and generate profit. The food safety incident further intensified these business contradictions.

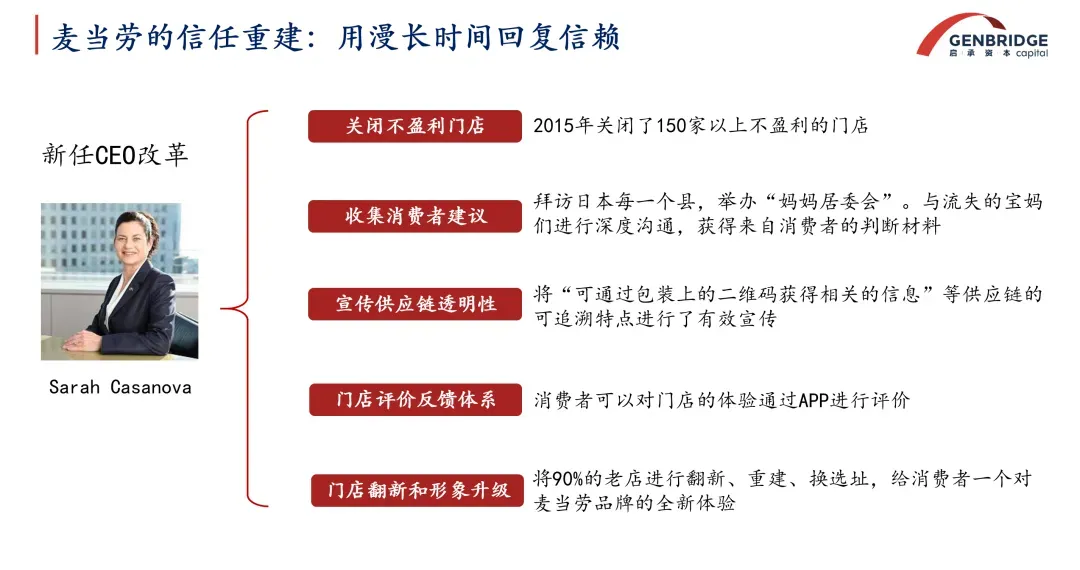

As a result, McDonald’s profit margins dropped significantly. To regain consumer trust, a new CEO was appointed. She spent over five years implementing reforms, including improving communication with customers, building a transparent and traceable supply chain, setting up a store feedback system, and revamping management practices to restore the brand’s performance.

These two cases demonstrate that hasty price cuts and supply chain risks must not be ignored. Even in an environment where everyone is chasing low costs, cost-effectiveness is not the only thing that matters.

Conclusion

For Chinese F&B companies, Japanese counterparts serve as valuable case studies. However, Chinese enterprises face four key limitations when learning from Japan's experience:

- Higher barriers to supply chain scaling in Japan

With a 39% food self-sufficiency rate (60% imported, 40% domestic), Japan relies heavily on globalized supply chains, outsourcing much of its pre-made food processing to China and Southeast Asia. This creates high procurement thresholds for new entrants, unlike China's abundant fresh food supply that readily supports chain restaurant expansion.

- Simpler menu standardization in Japan

Japanese cuisine features several staple dishes (udon, curry, beef bowls) that dominate daily consumption, with high carbohydrate proportions. These items are easier to replicate and standardize for large-scale operations.

- Cultural advantages in workforce management

Many leading Japanese companies operate without performance bonuses or equity incentives. Employees typically expect only marginally higher wages than market rates, yet maintain productivity despite limited motivational mechanisms.

- Absence of food delivery disruption

Japan's food delivery market maintains average order values around ¥65 RMB, with prices significantly higher than dine-in options - creating no economic incentive to disrupt traditional restaurant models.

These structural differences mean Chinese companies must adapt rather than directly copy Japanese strategies, particularly regarding supply chain localization, menu complexity, labor incentives, and delivery-driven competition. The learning lies not in replicating methods, but in understanding how to build systems suited to China's distinct market ecology.

In summary, the complexity of the food and beverage industry should never be underestimated. Unlike other sectors, success in this field isn't determined by any single capability—it's the comprehensive embodiment of multiple competencies. The industry uniquely combines characteristics from service, retail, and manufacturing sectors.

If we compare the development of F&B enterprises to a marathon race, competitors need more than just speed—they must avoid stumbling or taking wrong turns. A single misstep at critical moments could allow competitors to gain an insurmountable advantage. This industry requires both the stamina for long-term growth and the agility to navigate immediate challenges.