People often describe Japan’s post-bubble era as the “Lost Thirty Years.” However, for Japanese consumer companies, these thirty years were not lost—they forged even greater capabilities.

Even though consumers tightened their wallets and prices stagnated, the new market environment forced consumer companies to learn how to delight customers and lower operating costs. In this survival game, the competition is no longer about scale, but about who can better adapt to change.

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger have noted that there are two kinds of businesses in the world: those that create brilliant products, seizing a lead through flashes of brilliance; and those that stay smart, continuously evolving to meet competition.

The ever-changing, almost transparent retail industry clearly belongs to the latter. Every well-known Japanese company we see today has demonstrated a remarkable capacity for evolution:

To better understand consumer preferences, Suntory is willing to undergo 1,000 trials and dedicate 70% of its budget to iterating blockbuster products; 7-Eleven has restructured its supply chain, launching 200 new products every week; Saizeriya and Kobe Bussan have transformed into manufacturers, using production capabilities to build cost barriers... They remain highly sensitive to change and are always ready to adjust strategies. This adaptability will be the deciding factor in the era of stock competition.

In March this year, the GenBridge Capital team visited Japan again. They engaged with experts from enduring companies like 7-Eleven, Suntory, Ajinomoto, Saizeriya, and Kobe Bussan, discussing topics such as blockbuster product strategy, product development, private label brands, and low-cost operations—deepening our understanding of competition in a mature market.

This article is based on a conversation between Robert Chang, our Founding Partner, and Gloria Gu, our retail-focused investor. In this dialogue, they share reflections and insights from their recent learning trip to Japan. You can also listen to this conversation on our podcast (Xiaoyuzhou ID: 消费启示录).

A blockbuster product is neither achieved overnight nor a once-and-for-all success

People often marvel at the success of blockbuster products, but few talk about how difficult their creation really is. What many don’t realize is that behind every successful blockbuster, there are often thousands of failures.

In the 1990s, Japan’s green tea market was fiercely competitive, and many products didn’t survive beyond a month on the shelves. Suntory launched numerous new products during this time, only to see them all fail. Yet instead of losing heart, Suntory gathered lessons from each failure, upgrading everything from yeast technology and grinding techniques to tea quality and marketing strategies. Through this relentless effort, they finally developed the green tea brand Iyemon, which achieved sales of 70 billion yen in its first year on the market.

Creating a blockbuster is no easy feat. Even for Suntory, which holds multiple blockbuster products, the success rate for new product launches is only 0.3%.

However, Suntory’s enduring strength lies not just in developing blockbusters, but in sustaining them over extraordinarily long life cycles. Suntory Oolong Tea launched in 1981, BOSS Coffee in 1987, and Hibiki Whisky in 1989—products that remain popular worldwide even after more than 30 years.

The reason these blockbusters have remained bestsellers isn’t because their creators could foresee consumer needs decades into the future. Rather, their longevity is the result of constant iteration. Through unwavering consumer insight, Suntory has continuously updated its products to stay aligned with the spirit of the times.

Suntory believes that 70% of a company’s investment should go toward iterating and upgrading existing blockbuster products, while only 30% should be used to develop new potential offerings. They also believe that if a product’s packaging remains unchanged for two years, consumers will start losing interest.

Regarding Blockbuster Products: The second misconception — blockbusters also have a lifecycle.

As a product’s market penetration approaches its ceiling, companies must develop new blockbuster products to open up fresh growth curves and achieve the next leap forward.

Take, for example, the Japanese snack company Calbee. In its early days, Calbee’s success came from its hit products Kappa Ebisen (shrimp chips) and American-style French fries. However, during the 1990s, Calbee suffered a prolonged period of stagnating performance due to a lack of new products. It wasn’t until around 2000 that the company realized relying solely on existing blockbusters was unsustainable and that it had to invest in developing new products. This shift led to the creation of globally popular items like Jaga Pokkuru (potato snacks) and fruit granola.

From the cases above, it’s clear that consumer companies must maintain a grounded mindset—without fantasizing about achieving instant or permanent success through a single blockbuster. Instead, they must return to first principles: relentless consumer insight, accumulating small wins to eventually drive breakthrough change.

Imitating national brands is a dead end, private brands must be differentiated

When retailers venture into developing private brands (PBs), they often fall into a trap: sacrificing profit margins to chase sales volumes, positioning themselves as mere cheaper alternatives to national brands (NBs). While this tactic may boost short-term sales, it ultimately leads to a head-to-head battle with national brands, which is detrimental to the retailer’s long-term business development.

So, how should retailers approach their private brand strategy?

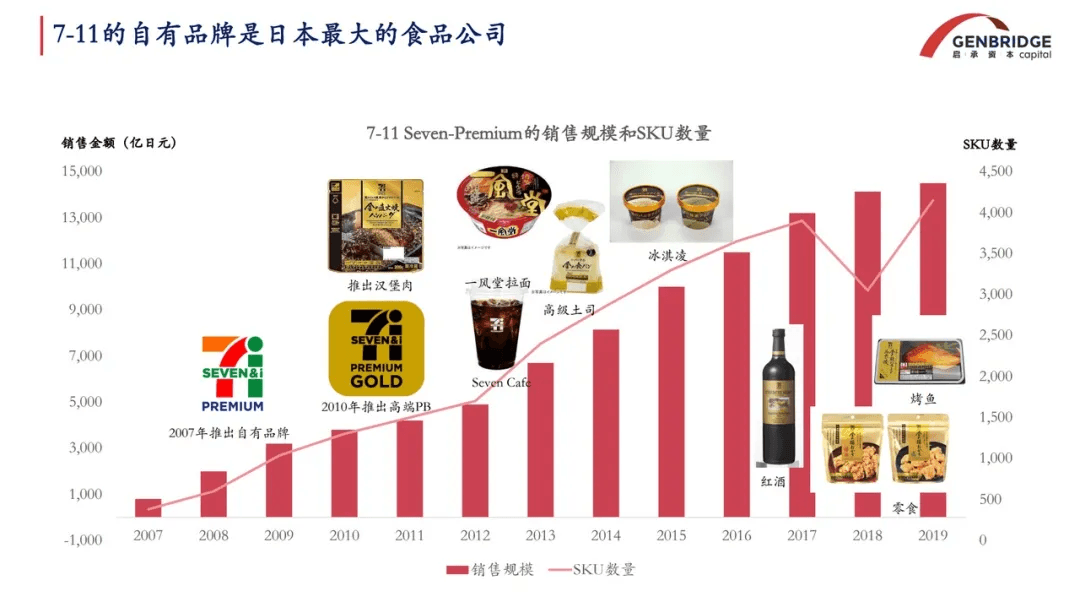

7-Eleven offers a compelling solution. Since 2007, 7-Eleven has heavily invested in its private brand business. Unlike typical approaches, 7-Eleven’s private label products are not cheaper; in fact, they are priced 20% to 30% higher on average than comparable national brand products. Yet, these offerings are still highly popular. If we isolate the sales figures for 7-Eleven’s private brand food products, the business alone would rank as one of Japan’s largest food companies, with annual revenues between 65 and 70 billion RMB.

How did 7-Eleven achieve this? By sharply differentiating its private brands. 7-Eleven sees national brand products as standardized goods available across all channels, designed for the “lowest common denominator” of national consumer needs. In contrast, private brands are meant to differentiate based on the characteristics of their own channels. 7-Eleven’s private brands focus on the specific needs of consumers around each store—its "private domain"—addressing unmet needs that standardized goods cannot fulfill.

In Summary, 7-Eleven applies the following criteria when selecting categories:

- Categories where NB product packaging does not meet in-store consumer needs: For example, NB products in personal care are often offered in large packaging sizes, which do not align with the "immediate" and "portable" consumption traits of convenience store shoppers. In these cases, 7-Eleven develops its own private label products, such as single-pack tissues, individual sheet masks, or small-sized laundry detergent bottles.

- Categories where NB competition is extremely intense and channel profit margins are very thin: If a product category is already at the center of a price war and stores find it hard to profit from these items, developing a private brand alternative becomes a way to extend the value chain and reclaim margins.

- Categories where NB products cannot keep up with 7-Eleven's fast product launch cycle: Due to the high density and limited space of convenience stores, there is greater sensitivity to specific usage scenarios and rapid trend shifts. At 7-Eleven, about 200 new products are launched every week, totaling around 5,200 new SKUs annually, with 70% of in-store products replaced every year. NBs often cannot meet such fast turnover requirements. For instance, in food categories, private brands can develop multiple flavor variations to satisfy consumers' desire for novelty.

Thus, for these differentiated private brands, deep consumer insight and the ability to launch new products at a high frequency are both the most critical and most challenging aspects. 7-Eleven’s organizational structure, product development process, and supplier collaboration model are all tightly aligned around this core principle.

Within 7-Eleven, merchandising, franchise operations, and recruitment are defined as the three profit-driving departments, with the merchandising department being the only one directly responsible for improving the company’s gross margins. The merchandising team is structured by category, and each category manager oversees both NB procurement and PB development within their scope.

Unlike traditional linear product development processes, 7-Eleven adopts a roundtable development model. For example, when developing a new coffee product, 7-Eleven brings together all relevant suppliers—coffee roasters, ice manufacturers, paper cup producers, motor manufacturers, design agencies, and more—into a single roundtable. 7-Eleven directly manages procurement from each supplier, minimizing markup layers while fostering cross-functional collaboration from the start.

Like many Japanese Consumer Brands, 7-Eleven also combines “52-Week Merchandising (MD)” with the “PDCA Cycle” for Product Development. Within the 52-week planning schedule, 7-Eleven maps out all hypotheses, validations, and timelines based on consumer scenarios at different times of the year.

For instance, March and April are financial reporting season in Japan, when office workers tend to work overtime. Therefore, 7-Eleven strengthens its offerings of fresh food bento boxes during this period.

At the end of each week, they input actual sales data to verify the hypotheses.

Through this method, 7-Eleven transforms what might seem like creativity-driven product development into a highly granular and tightly managed process. This provides the fundamental support for its relentless pace of new product launches.

World-Class retail and service companies are often world-class manufacturers

In the past two years, "low-price competition" has become a consensus across the consumer sector. Brands like Mixue Ice Cream & Tea, Mingming Is Busy, and Guoquan Food have emerged as highly celebrated "price slayers."

However, many people misunderstand what "low-price competition" really entails, mistakenly believing that simply cutting prices will secure victory.

In reality, this only means sacrificing gross margins, either your own or your partners’, without fundamentally changing the cost structure. True, healthy low pricing requires cost design across the entire value chain right from the start, achieving excellence at every stage.In other words, the best retail and service companies often possess top-tier manufacturing capabilities, allowing them to operate at low cost sustainably.

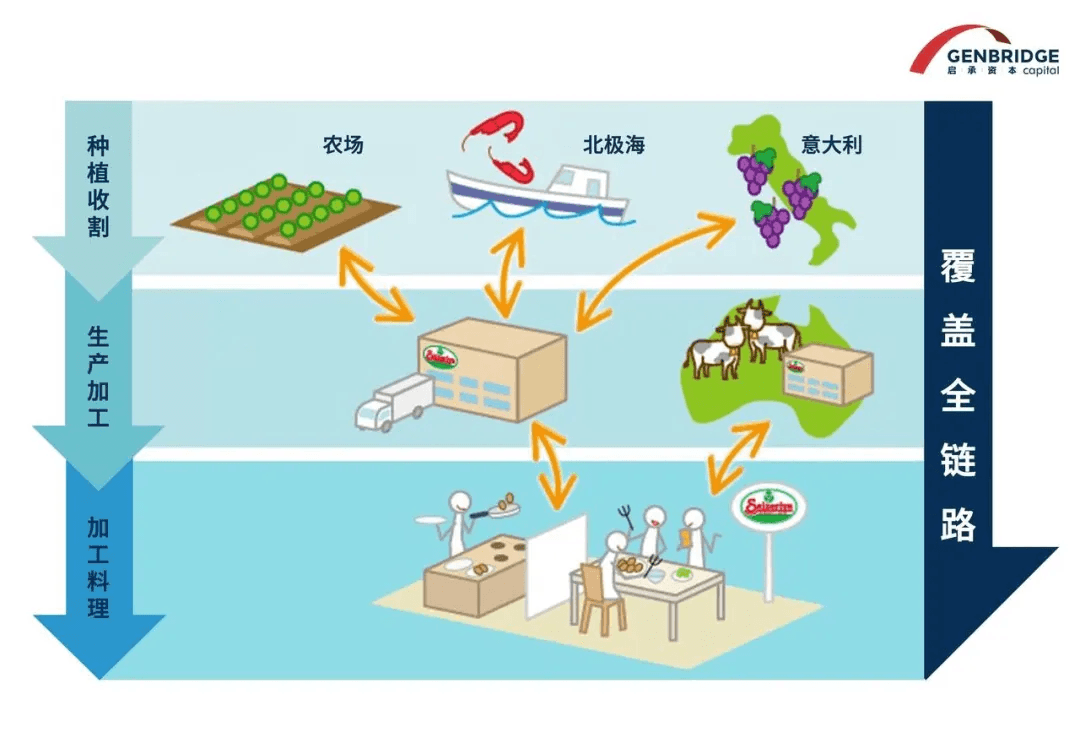

During this study trip, we had the opportunity to exchange ideas with experts from Kobe Bussan’s Gyomu Super business. Although Kobe Bussan operates supermarkets, the entire organization regards itself as a manufacturing company, aspiring to be an “infrastructure provider for food.” To that end, Kobe Bussan continuously acquires companies across different categories and now owns 25 manufacturing plants.

Interestingly, Kobe Bussan does not acquire the most efficient or highest-performing factories. Instead, they acquire companies on the verge of bankruptcy—or already bankrupt—and through their operational expertise, maximize capacity utilization to achieve ultra-low manufacturing costs.

Deep involvement in manufacturing also creates opportunities for differentiated products. At Kobe Bussan, you can find innovations like yokan (sweet bean jelly) packaged in milk cartons and cheese ice cream sold in tofu containers—quirky ideas born from the product development team’s efforts to boost factory revenues.

Saizeriya, a major affordable Italian restaurant chain, places great emphasis on manufacturing capability.

Former president Kazutomi Horino stated that manufacturing is far more mature than service industries, and that factories are designed and operated through precise calculations.He believed that by introducing manufacturing know-how into the service industry, businesses could achieve greater efficiency and productivity.

At its frontline stores, Saizeriya applies factory management methods to reduce operational costs.

For example:

- To avoid slip risks from wet floors, Saizeriya’s kitchens use a dry floor system.

- To save electricity, outdoor AC units are installed in shaded areas and regularly sprayed with water to stay cool.

- Dishware has been replaced with resin materials to reduce breakage and replacement costs.

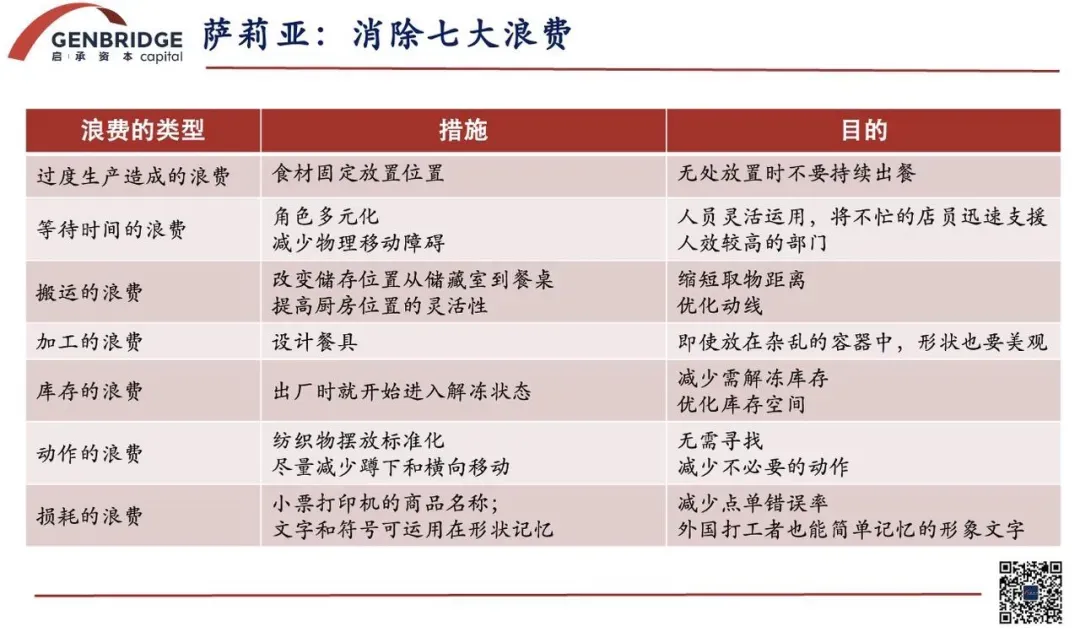

Saizeriya even adapted the Toyota Production System’s “Seven Wastes Elimination” guidelines, turning what are often overlooked details in restaurants into standard operating procedures.

Saizeriya takes manufacturing to the next level even in its supply chain.

The company owns its own factories in Australia, producing items like hamburger steaks and white sauces. Their blockbuster product, “Milano-Style Doria” (baked rice with sauce), uses these Australian-made sauces.

In addition, Saizeriya cultivates its own lettuce in Japan. While a regular head of lettuce yields only 2–3 salad servings, Saizeriya bred a larger variety capable of producing 5–7 servings per head.

For kitchen operations, Saizeriya adopts a well-known central kitchen model, where ingredients are processed into semi-finished products before being delivered to stores. This not only reduces the need for back-of-house labor but also enables standardized food quality and faster service turnover—both crucial for improving table turnover rates.

It is precisely this world-class manufacturing capability that has enabled Saizeriya to become the largest Italian restaurant chain by store count worldwide.

Conclusion

Whether a company can rigorously execute scientific product development processes reflects its maturity in management systems and talent cultivation. Objectively speaking, Chinese enterprises still have significant room for improvement in this area.

Thus, when learning from these methodologies, we should avoid rushing to replicate outcomes. Instead, we must proceed step by step, adapting to our own competitive advantages and market environments, gradually building teams, systems, and consumer insights through localized practice.

As a steadfast supporter of China's consumer sector, GenBridge will continue to plan study tours to Japan and share research findings. We hope to move forward together with you.