What kind of drinking water can sell for €99 (approximately RMB 820) per bottle?

Topping the list of the “world’s most expensive water,” Svalbarði Water has its own story to tell. Sourced from a 4,000-year-old ancient glacier in Norway, it is prized for its purity and scarcity, while drawing attention to the environmental issue of glacial melting. Its highly artistic design and sustainability ethos have made it a preferred choice for high-end gifting and Michelin-starred restaurants.

A bottle of water priced at €99 may sound sensational. Yet in everyday life, “premium-priced water” is far from rare, and there is no shortage of consumers willing to pay for it.

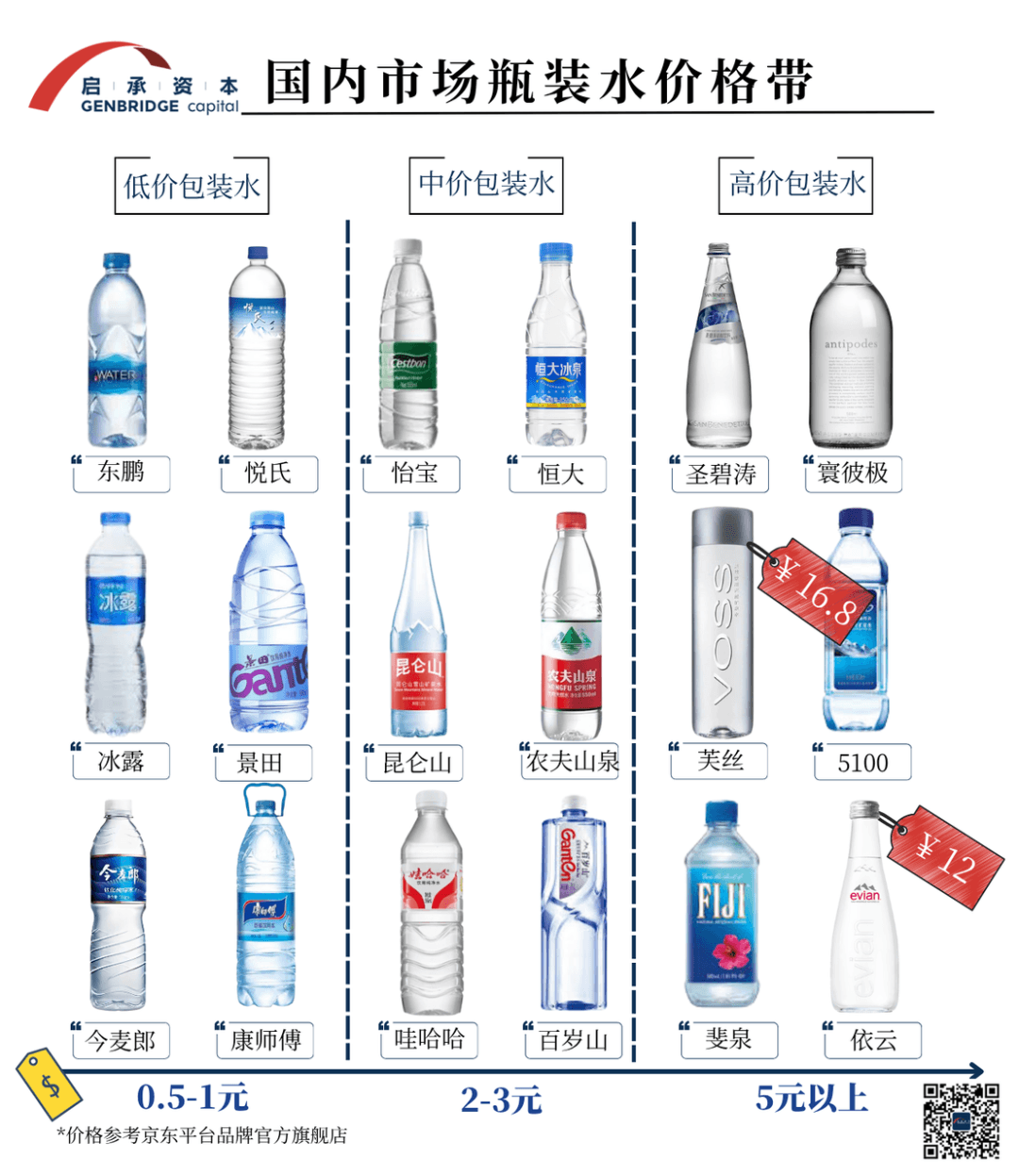

For example, in the domestic market, bottled water prices range from RMB 1 products like Jinmailang to premium brands such as VOSS, priced above RMB 10—representing a price spread of more than tenfold.

Regardless of which bottle of water you favor, this comparison inevitably raises a question: if all bottled water serves the same purpose of quenching thirst—and most people cannot even distinguish the taste—where does this tenfold price difference really come from?

If we look only at functional attributes, such a wide price disparity in bottled water would be impossible to justify. To answer this question, we must introduce the concept of “user value”—which goes beyond basic functionality to include experience, storytelling, and identity, addressing consumers’ holistic needs.

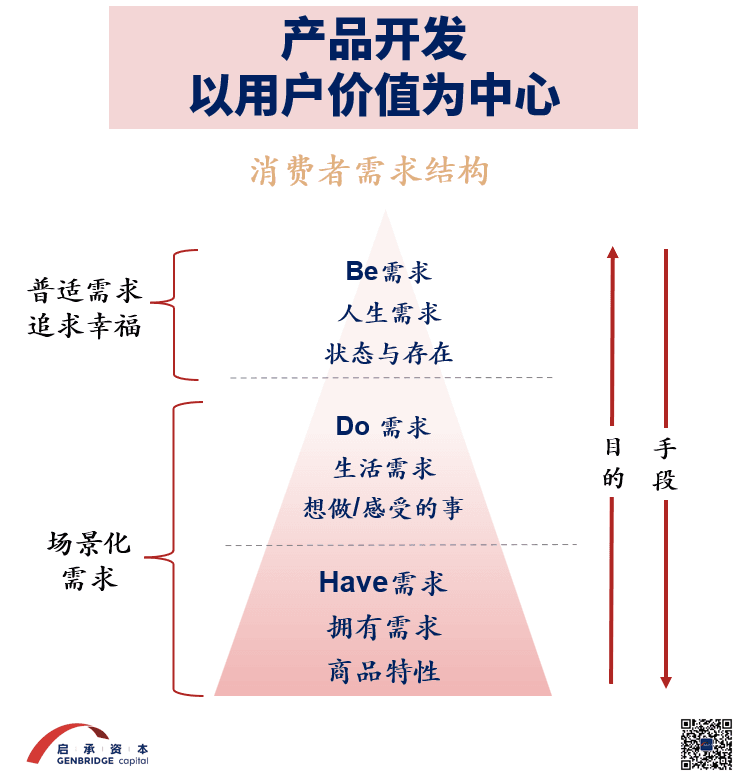

In this article, we will use the “Be–Do–Have” model to understand the different user values addressed by bottled water across price tiers. This model is a powerful tool for uncovering deep user motivations—many era-defining products, such as Sony’s Walkman and Nintendo’s Wii, were developed under its guidance.

Based on the Be–Do–Have framework, we can further explore how differentiated user value can unlock new market opportunities. We hope these cases and models offer meaningful inspiration to you.

Decoding User Value: The Be–Do–Have model

The Be–Do–Have model originated in the field of personal development and integrates principles from self-determination theory, identity theory, and behavioral psychology. It has since been widely applied in product development and business analysis.

It breaks down complex user needs into three layers:

• HAVE: the ownership layer—what specific product I need to have.

• DO: the action layer—the usage context and experience, such as “What is my consumption scenario?” or “What kind of experience do I want?”

• BE: the being layer—one’s ideal state and self-actualization, answering the question “Who do I want to become?” and reflecting fundamental psychological needs.

Take drinking coffee in the morning as an example. At the surface level, the need is “I need a hot cup of coffee.” A deeper layer reveals motivations such as “to quickly feel alert” or “to appear professional in a business meeting.” At the deepest level, the motivation may be “I want to be an efficient business professional.”

These three layers form the internal logic of consumer decision-making, following a top-down driving relationship:

The desire of who we want to become (Be) determines what we choose to do (Do);

What we choose to do (Do) then determines what we need to have (Have).

Returning to the coffee example, when a consumer decides to drink coffee in the morning, the decision chain looks like this:

• Be (Identity/Goal): I want to become a business leader who can calmly command situations and lead teams.

• Do (Action/Scenario): To achieve this, I need to have an efficient meeting with key partners in the CBD at 9 a.m.

• Have (Tool/Resource): Therefore, I need a quiet café in the CBD that opens at 8 a.m. and serves freshly brewed SOE coffee to facilitate this meeting.

Once this relationship is understood, a key business insight emerges:

If a brand competes only at the “Have” level—simply claiming “I am a better cup of coffee”—it will inevitably be trapped in competition over function, price, and efficiency. By contrast, exploring user experience (Do) and identity (Be) may open up entirely new possibilities.

Now, let us return to the world of bottled water with this model and examine how its value logic unfolds.

From Have to Be: The three value battlegrounds of bottled water

In the world of bottled water, “Have” represents the most basic functional value—quenching thirst; “Do” refers to the context and purpose of drinking water; while “Be” represents the identity narrative implied by choosing a particular type of water.

We will examine one representative brand at each price tier.

1. Low-Priced Water (~RMB 1)

Jinmailang: Maximizing the “Have” Layer

Jinmailang is a textbook example of pushing the “Have” strategy to its extreme. Its core philosophy is not about creating experiences or symbolic identity, but about focusing on the most fundamental goal: enabling consumers to “have” a bottle of thirst-quenching water at the lowest cost and with maximum convenience.

Price is its core weapon. Taking the newly launched “Blue Label Water” as an example, whether at a retail price of RMB 1 or discounted online prices as low as RMB 0.5 or even lower, Jinmailang sends a clear and direct message: “I am the most cost-effective water you can buy.”

To achieve this, Blue Label Water forgoes multi-size and multi-scenario product innovation, committing fully to pragmatism. All marketing resources—from positioning itself as the “king of value for money” to emphasizing “market-leading sales”—reinforce this single-minded positioning. Even its brand ambassadors are mainstream, relatable celebrities, placing all bets firmly on the physical “Have” layer.

Correspondingly, through an extremely streamlined SKU structure, Blue Label achieves tight control over its supply chain and costs, forming a price barrier to some extent. It perfectly satisfies the basic need of “a cheap and convenient bottle of water to quench thirst,” making it a textbook victory of the “Have” strategy.

2. Mid-Priced Water (RMB 2–3)

Nongfu Spring: A Master of the “Do” Experience

Unlike Jinmailang’s extreme focus on price and basic thirst-quenching (Have), Nongfu Spring’s success lies in elevating the experiential value of the simple act of drinking (Do). It rarely emphasizes price or cost advantages, instead turning drinking water itself into a positive experience associated with health and nature.

An examination of Nongfu Spring’s packaging and marketing reveals that elements traditionally belonging to functional value (the Have layer) are transformed into experiential value (the Do layer).

The most striking example is the iconic slogan: “We do not produce water; we are merely porters of nature.”This brilliant line clearly differentiates Nongfu Spring from all other bottled water brands.

The value it conveys is no longer “quenching thirst,” but “receiving a healthy gift from nature.” Whether through promoting pristine sources such as Changbai Mountain and Qiandao Lake, or through the iconic landscapes on its bottles, all elements serve as evidence reinforcing its “natural and healthy” experience.

To further reinforce the perception and experience of “natural and healthy,” Nongfu Spring embeds itself deeply into consumers’ lives through highly targeted, scenario-based products.

For specific moments with higher water-quality requirements—such as infant care or home tea brewing—it launched products like baby water and tea-brewing water.

These specialized products target moments where consumers care most about health and quality (Do), while offering precise solutions (Have), firmly associating the brand with “high quality” and “trustworthiness.”

The ultimate demonstration of Nongfu Spring’s dominance at the “Do” level is when numerous well-known restaurant brands began promoting “cooked with Nongfu Spring water” as a selling point.This signals that Nongfu Spring has successfully defined the act of drinking its water as a pursuit of health and quality.

In summary, Nongfu Spring’s success represents a textbook victory of the “Do” strategy.

Rather than battling low-end water brands on price (Have) or competing head-on with premium brands on identity (Be), it used strong brand storytelling and scenario-based products to imbue drinking water with meanings of “health” and “nature,” securing the broadest mainstream market.

3. Premium Water (>RMB 10)

VOSS: Selling the Aspiration of “Becoming”

提到高端水,VOSS是一个绕不开的挪威品牌,以其标志性设计和奢华定位闻名全球。

When it comes to premium water, VOSS is an unavoidable Norwegian brand, globally renowned for its iconic design and luxury positioning.

When it first entered China, its glass-bottled products were priced above RMB 20 per bottle, becoming a symbol exclusive to top-tier consumption venues.

In recent years, through a partnership with Reignwood Group, VOSS launched a localization strategy—adopting Chinese water sources and introducing PET bottles, bringing prices into the RMB 10 range. Even so, it remains 5–6 times more expensive than Nongfu Spring.

What makes VOSS disruptive is that, unlike other premium water brands that emphasize long histories or scarce sources (such as Evian’s Alpine water source in France), VOSS builds its story around “creation”—the creation of an ideal in which water can become a symbol of luxury and elegance—and constructs a complete “Be”-level value around this vision.

Step One: Defining the product through design, turning the bottle into a symbol of identity. The founding team of VOSS enlisted a former Creative Director of Calvin Klein, drawing inspiration from perfume bottles to design its iconic cylindrical glass bottle. This minimalist yet elegant design makes it stand out on shelves. It is not merely packaging, but the core differentiation of the product itself. When consumers purchase VOSS, they are to a large extent buying the aesthetics and taste embodied in the bottle, which has thus become a displayable “fashion statement” and a social signaling tool.

Step Two: Defining scenarios through channels, binding the brand to the high-end. To embed its role as a “symbol of identity,” VOSS strictly controlled its distribution channels in the early stage, appearing only in venues that define “premium.” For example, it could be found in guest rooms of luxury hotels such as The Ritz-Carlton, Grand Hyatt, and W Hotels, as well as on the tables of Michelin-starred restaurants like Xin Rong Ji.

In these settings—where price sensitivity is low but taste consciousness is high—VOSS successfully bound itself to concepts such as “luxury” and “exclusivity,” laying a solid cognitive foundation for maintaining premium pricing when later entering boutique supermarkets such as Ole’.

Step Three: Defining spirit through narrative, turning celebrities into embodiments of value. VOSS’s brand narrative cleverly draws on Norway’s national image to tell a modern story of “purity, excellence, and responsibility.” More importantly, it concretizes brand value by aligning with key opinion leaders. From Madonna establishing its early tone of “niche sophistication,” to later collaborations with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson that expanded the brand image into an “aspirational elite lifestyle” desired by the mass market.

In China, VOSS has also frequently sponsored and appeared at events such as Shanghai Fashion Week, international equestrian championships, and high-end art fairs. Through repeated visibility in these contexts, it clearly communicates to consumers: those who drink VOSS are the kind of people I aspire to become.

At this point, the fundamental difference between VOSS and Nongfu Spring becomes clear. Nongfu Spring’s value proposition is inward-facing: “What I am” (I am natural and healthy water). VOSS’s value proposition, by contrast, is outward-facing: “What I can help you become” (I can showcase your taste and make you appear more elegant and successful).

In summary, VOSS’s success represents a victory of the “Be”-level strategy. It powerfully demonstrates that even in a highly functional red-ocean market, as long as a brand can connect with consumers’ deepest desire for “becoming,” its value ceiling can be lifted without limit.

Conclusion: Beyond the product, back to user value

Returning to our original question: why can a single bottle of water create a tenfold value gap?

Through the cases of three brands, we can clearly see that the answer lies in the different layers of user needs they address: Jinmailang focuses on “Have,” Nongfu Spring cultivates “Do,” while VOSS sells “Be.”

This offers two core insights for product development and brand innovation.

First, true differentiation comes from deep insight into user needs.

When a product’s physical function (Have) is fully satisfied, competing only at this level will inevitably lead to price wars. Real opportunities for innovation come from moving upward to explore users’ contextual experiences (Do) and identity recognition (Be), entering the market from different value dimensions.

Second, pursue greater value rather than simply being “more expensive.”

Exploring the “Do” and “Be” layers is essentially about creating added value beyond function. In our cases, higher value leads to higher willingness to pay, because the product shifts from a “necessity of life” to something “deeply desired.”

However, it must be made clear that the goal is to create value, not merely to signal high prices.

Simply making a product expensive is not difficult—it can be achieved by piling on premium materials. But if a brand can meet users’ deeper needs through deep user insight without significantly raising prices, it stands to win a much broader market.

All of this points to a fundamental question: how can we scientifically and systematically understand users, and uncover the real needs hidden at the “Do” and “Be” levels?

This is precisely the core topic we will explore in our next article. Stay tuned.