Preface: Industry champions who cracked fashion’s “impossible triangle”

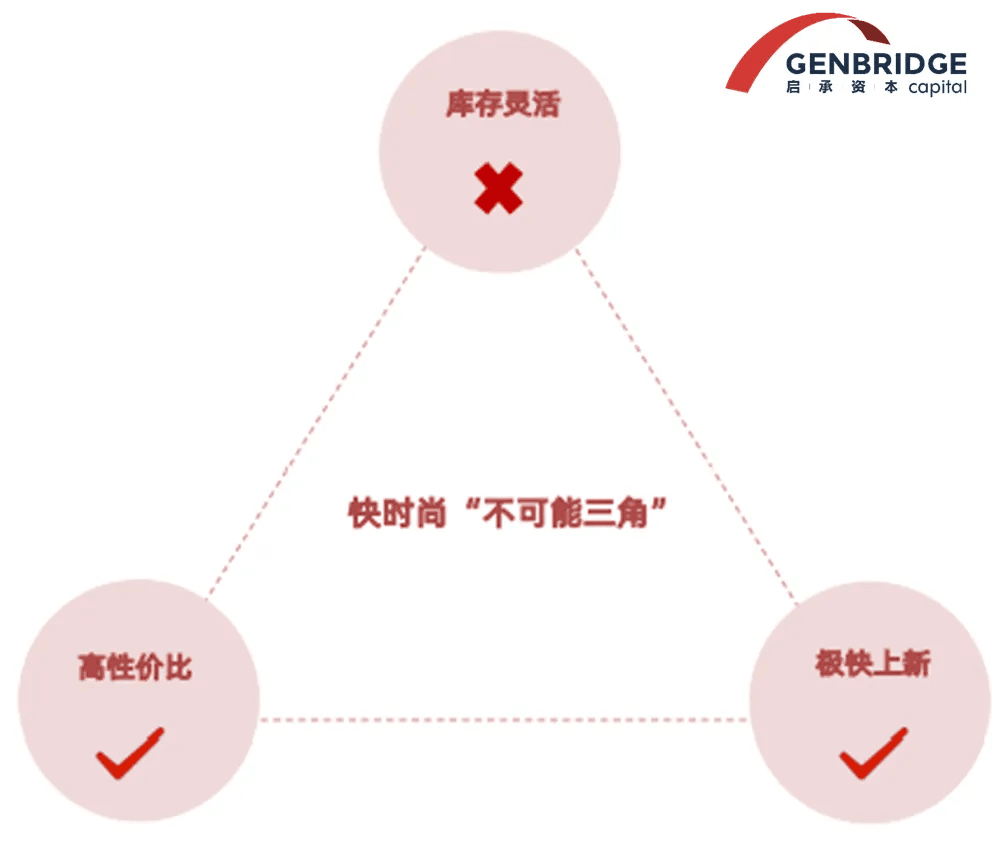

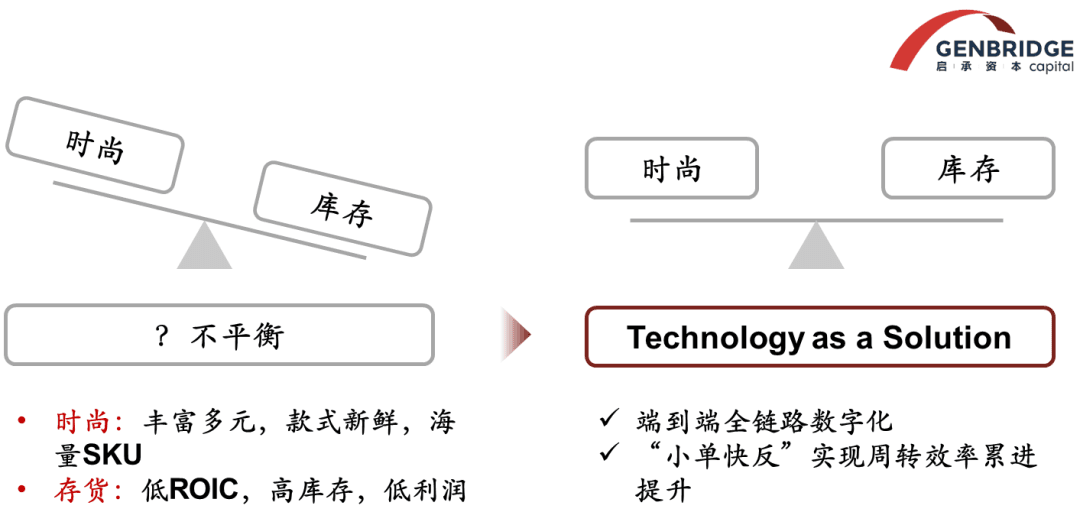

The fashion industry is vast in scale, yet highly fragmented. It’s rare for companies to surpass the 10-billion-RMB threshold. Product turnover is extremely rapid—fashion is like “fresh produce that constantly changes styles.” The core pain point of the industry lies in the challenge of reconciling an “impossible triangle”: flexible inventory, ultra-fast product launches, and high cost performance—all at the same time.

Fast fashion has become a high-value segment within the apparel sector. As the industry evolves, some fast fashion companies have overcome its systemic constraints through business model innovation, successfully cracking the “impossible triangle.”

In this article of "Cycle-Resilient Consumer Champions," we will break down how fast fashion giants UNIQLO (Fast Retailing), ZARA (Inditex), and SHEIN each tackle the challenges of fast fashion:

First, we reconstruct the context of the times in which these giants emerged, and the founding visions that shaped their companies.

Then, we analyze their business models from the perspectives of brand positioning, innovation strategies, and operational tactics.

We hope this content can serve as a useful reference for other players across the apparel value chain looking to innovate and upgrade.

Note: This article makes multiple references to Takahiro Saito’s book

The Rise of Industry Giants: When the times make the hero

The year 1980 marked a turning point in the development of the fashion industry. Before this, fashion operated under a model where production and sales were separate, and department store channels dominated. Long value chains, high markups, and inflexible discounting made it difficult for consumers to enjoy both quality and value.

After 1980, ZARA and UNIQLO began to rise. Representing the SPA model (Specialty retailer of Private label Apparel), these companies pioneered a vertically integrated system—from product planning and manufacturing to retail—allowing consumers to access better quality at lower prices.

By 2010, the SPA model underwent further iteration:

Offline, both ZARA and UNIQLO saw single-digit growth. With market saturation and intense competition, discount retailers began to eat into their excess profits.

Online, super platforms and independent direct-to-consumer sites delivered faster and richer front-end sales data. Information transmission became 10 to 100 times more efficient, paving the way for new players like SHEIN.

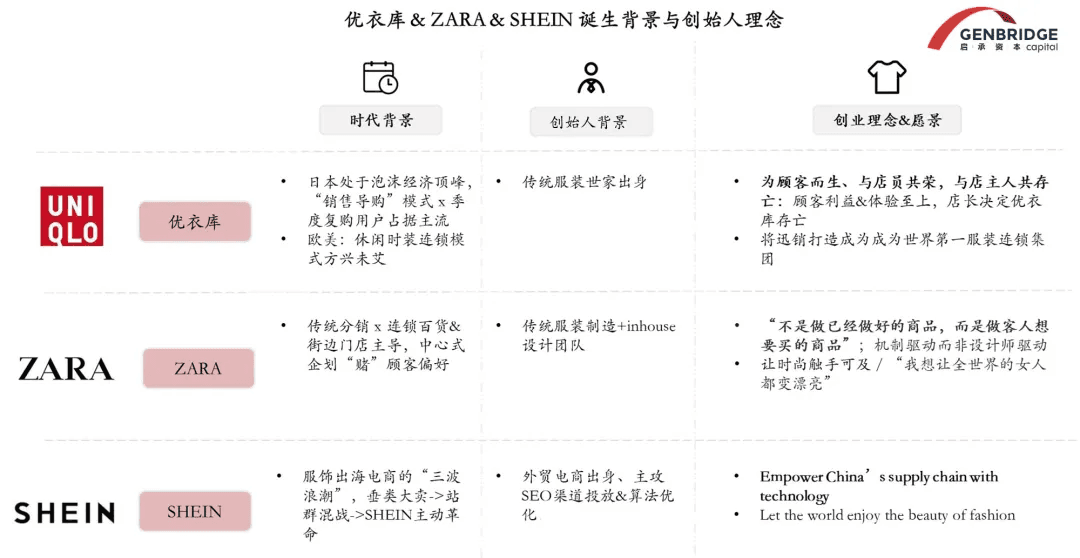

As titans in the fast fashion space, the rise and business model innovations of UNIQLO, ZARA, and SHEIN are deeply intertwined with the defining features of their eras and the distinct backgrounds of their founders:

UNIQLO

Founded in 1984 during the height of Japan’s economic bubble, when the strong yen drove up fashion prices, UNIQLO made a bold move to adopt self-service apparel retail at a time when the sales-associate model dominated. Founder Tadashi Yanai, from a traditional garment family, built the company with a vision to “change clothing, change the world.” His commitment to setting ambitious long-term goals helped drive UNIQLO’s “incredible, large-scale growth.”

ZARA

Founder Amancio Ortega also had a background in apparel, but with a stronger focus on manufacturing. Early on, he assembled his own design team. After a downstream client suddenly canceled a wholesale order for tourists, he decided to extend the business downstream and opened his own stores. Thus, ZARA was born in 1975. In an era dominated by traditional distribution, department stores, and street-front retailers, ZARA abandoned centralized planning based on forecasting customer preferences. Instead, it emphasized a culture of equality, operational mechanisms over star designers, and a system in which “ZARA can run without any single individual.”

SHEIN

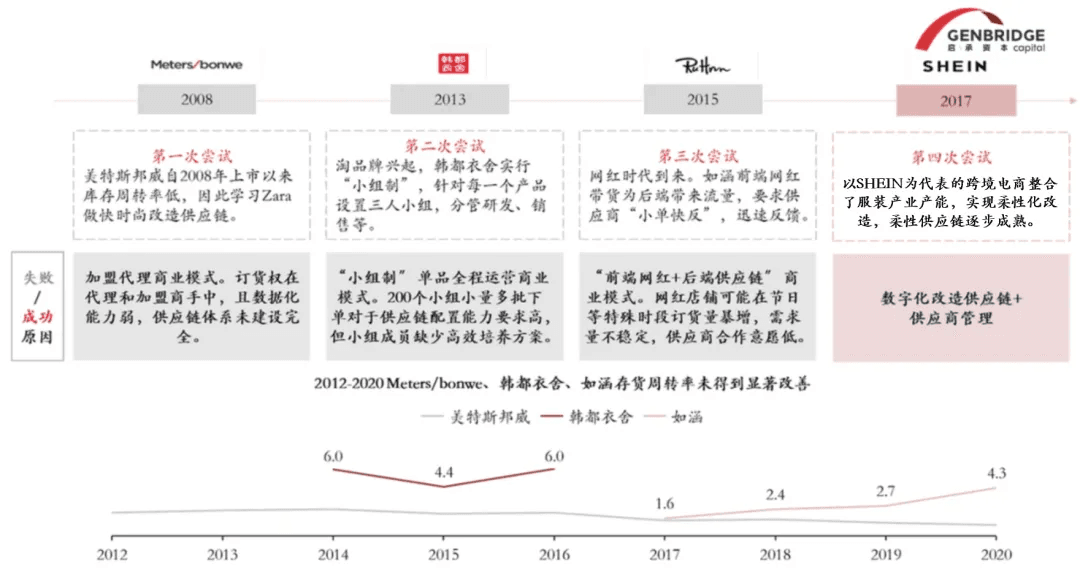

Turning to China, the fast fashion e-commerce sector also experienced three waves of development. Earlier players like Metersbonwe, Handu Yishe, and Ruhan all experimented with the small-batch, quick-turnaround model. But it wasn’t until SHEIN that the model was successfully scaled.

The apparel export industry that SHEIN operates in has undergone three major phases of evolution:

Phase 1.0 (2008–2010): Chinese sellers leveraged low-cost apparel clusters to enter the to-C export market, led by wedding dresses. However, the market was chaotic, plagued by “image-based selling” and rampant mismatches between pictures and actual products.

Phase 2.0 (2011–2012): Players like LightInTheBox and Aopeng popularized the "multi-site" model, experimenting with early fast-turnover strategies. By creating category-specific sites for various styles and demographics, they capitalized on the search engine traffic boom to rapidly connect with consumers. But this “quick and dirty” traffic strategy eventually hit a ceiling when Google tightened its advertising policies.

Phase 3.0 (2013–present): The “small-batch, quick-turnaround” model matured, supported by better data systems and more efficient supply chain feedback. Growth in this phase surpassed that of the multi-site model. SHEIN seized this new wave of traffic dividends, using dresses as its breakthrough category and quickly scaling up, setting its growth flywheel in motion.

SHEIN summarizes its business model as: “We use technology to solve the fashion inventory mismatch.”

It aims to optimize the end-to-end supply chain cycle through a fully integrated data feedback system—leveraging technology to increase efficiency at every stage.

Brand Positioning: Choosing the main battleground

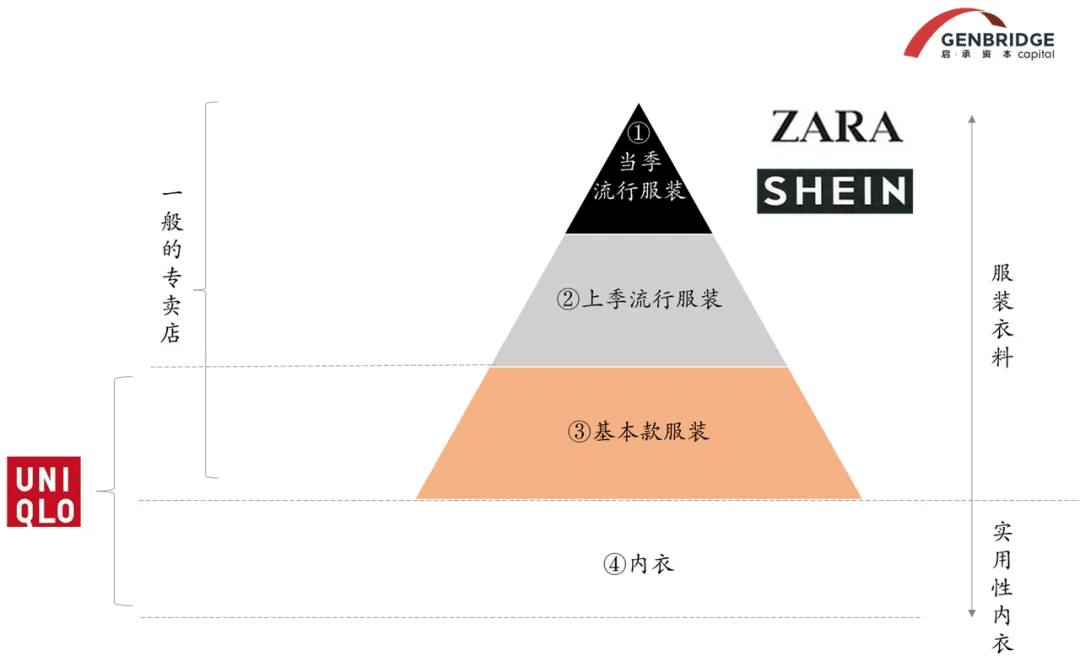

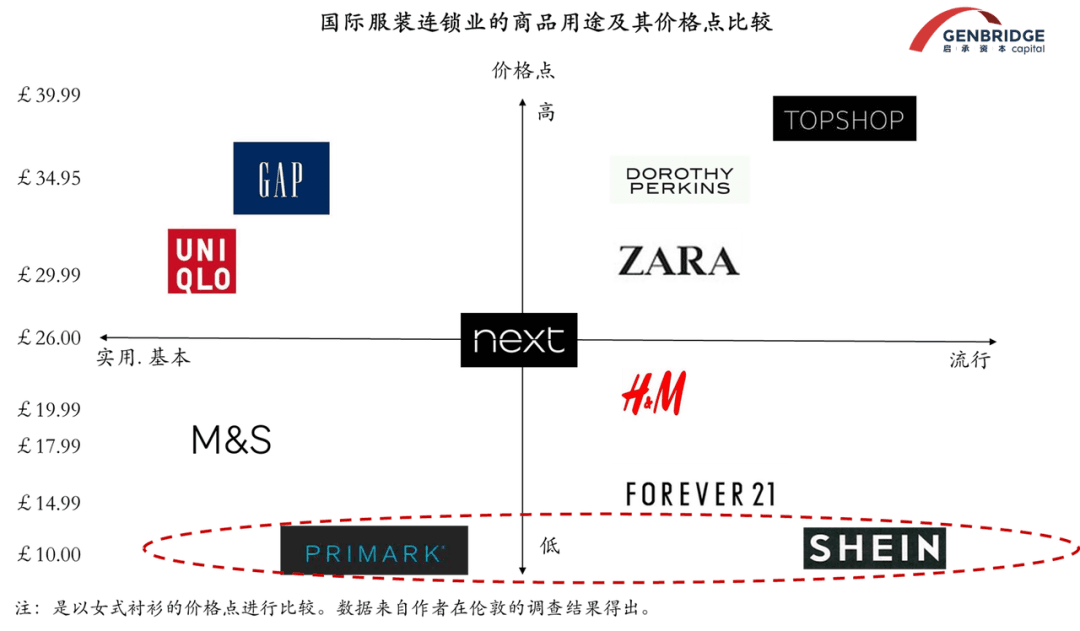

The three companies—UNIQLO, ZARA, and SHEIN—differ significantly in their brand positioning: UNIQLO focuses on wardrobe basics and innerwear, ZARA and SHEIN cater to seasonal fashion driven by fast fashion trends. Based on these differentiated positions, each company has developed its own core operational capabilities.

UNIQLO: Universal Appeal × Basics × High Quality at Low Prices

UNIQLO: Universal Appeal × Basics × High Quality at Low Prices

UNIQLO offers casual basics suitable for anyone, anytime, anywhere—balancing fashion and quality. It strategically avoids trendy apparel, which significantly extends product life cycles and helps mitigate inventory issues caused by rapid trend turnover.

UNIQLO's retail-driven operations are guided by four key principles:

- Maximize target audience reach

- Provide high quality at affordable prices

- Minimize operational costs

- Maintain abundant stock of core products

For example:

Products are typically basic items priced around RMB 100. Store locations started in suburban areas using a self-service model, offering customers a 3-month unconditional return policy.

Since most shoppers visit UNIQLO with a clear purchase intent, ensuring that they can find the right size and style is crucial—thus, core items must be well-stocked and never out of stock.

ZARA: Professional Women × Coordinated Fashion Sets × Affordable Quality

Unlike UNIQLO, ZARA sells fashionable outfits centered on styling and full-look coordination. Its core audience is professional women who want to look stylish but cannot or prefer not to pay high designer prices. ZARA built around “her” and extended into sub-brands like ZARA Man, ZARA Kids, and ZARA Basic.

ZARA follows a principle of providing department store-level quality at half the price. Department stores typically promote items with 30% discounts; ZARA deliberately sets its prices at 50% of comparable department store goods, thus lowering consumers’ perceived opportunity cost and improving store turnover efficiency.

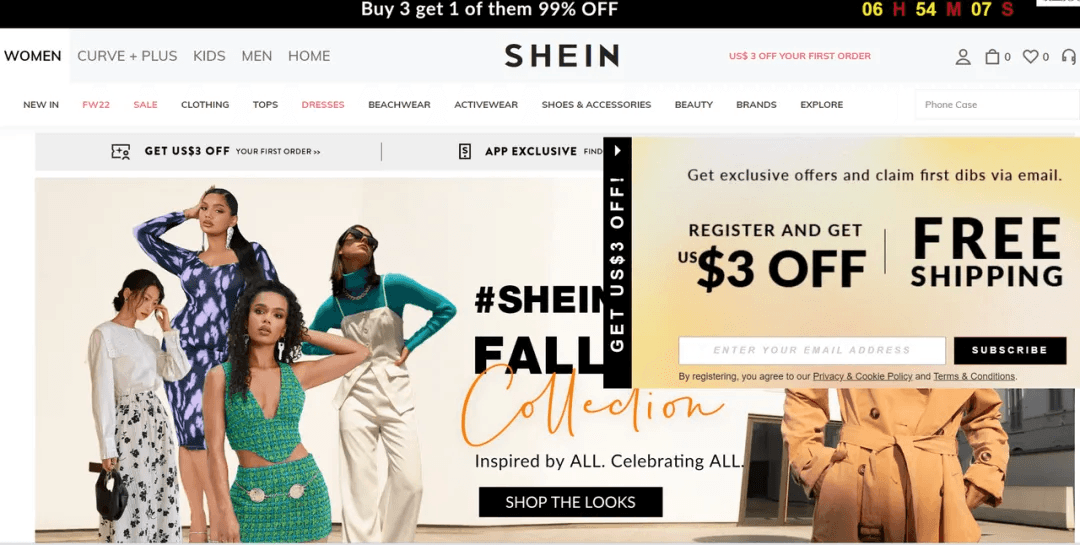

SHEIN: Fashionable Women × Hyper-Personalization × Ultra-Low Prices

SHEIN’s audience overlaps with ZARA’s, but with a key difference: its customers are also digital natives, largely composed of Gen-Z consumers. SHEIN covers all scenarios and style categories relevant to its target group.

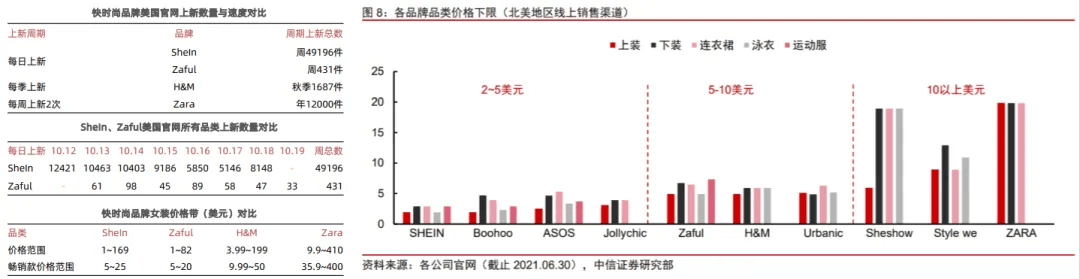

While ZARA introduces trend-based collections quarterly, SHEIN operates a data-driven, end-to-end supply chain model that enables automatic product reordering and optimization—from product selection to restocking.

SHEIN leverages backend sales feedback to determine optimal production combinations and refine personalized exposure strategies. With its full-chain data integration, SHEIN delivers:

- Hundreds of times more product launches than ZARA

- Even lower prices with greater variety and speed

Business Model Innovation: Breaking the “impossible triangle”

Traditionally, the fashion industry has struggled to simultaneously offer flexible inventory, fast product launches, and high cost-efficiency. This is due to fragmented consumer demand and long product planning cycles, which often span 6 to 12 months.

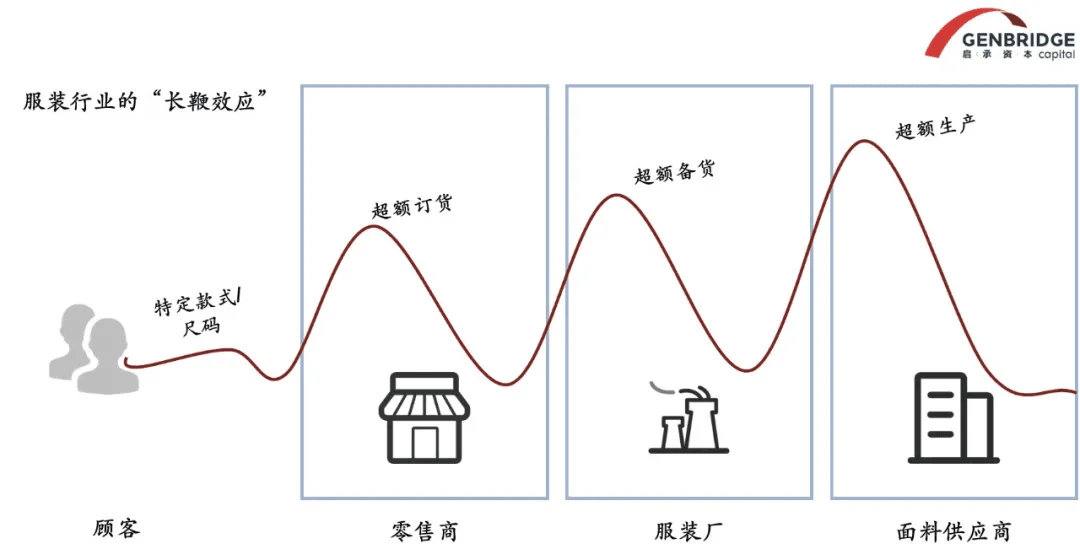

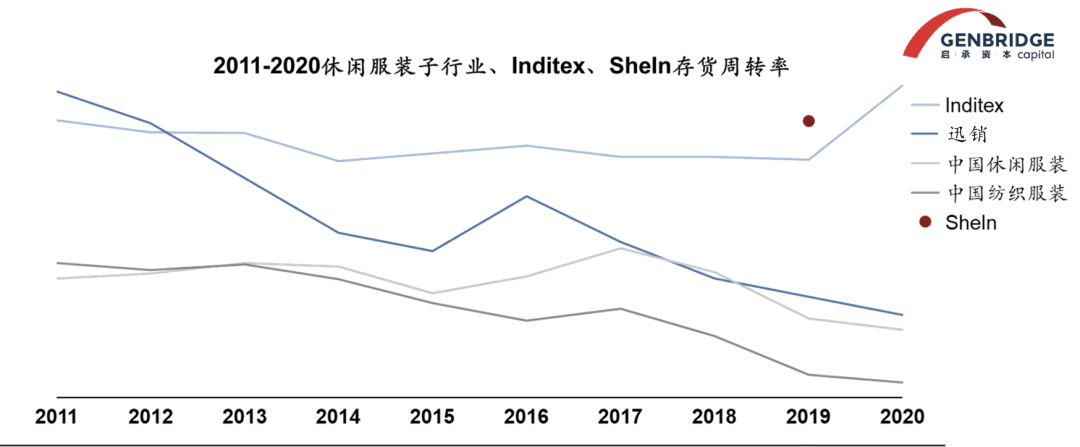

The inability to match demand precisely leads to upstream overstocking—a phenomenon known as the bullwhip effect, which lies at the heart of supply chain inefficiencies.

To crack this “impossible triangle” in fashion, each company took a different path of business model innovation:

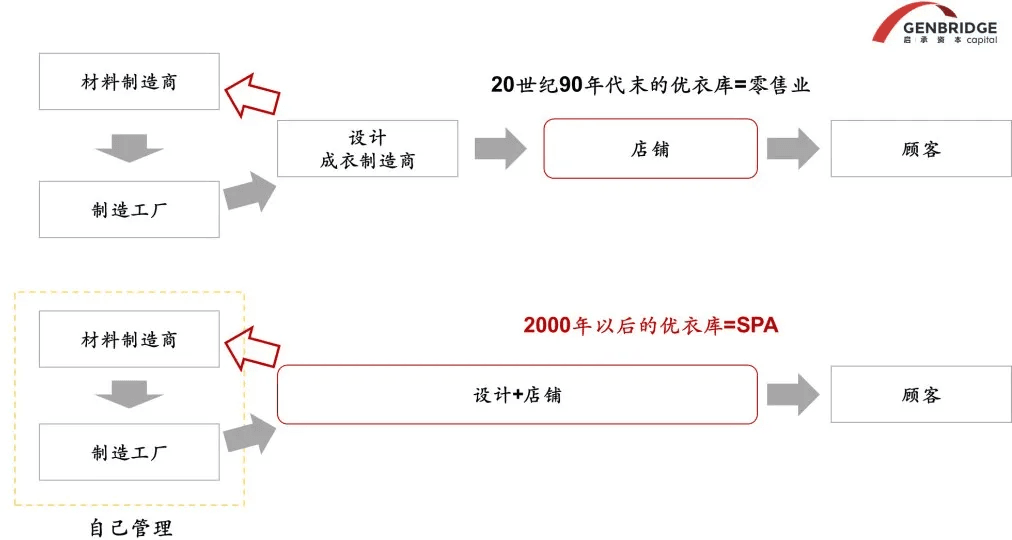

After 2000, UNIQLO adopted the SPA (Specialty retailer of Private label Apparel) model, which enabled it to directly engage in upstream design and manufacturing.

Benefits of SPA:

- Sales data from retail channels are quickly fed back upstream, improving forecasting and inventory turnover

- Integrated production and retail reduce overall markup across the value chain, allowing better quality at lower prices

- UNIQLO focuses on a narrow range of basic apparel, working with a streamlined set of a few dozen suppliers

- Large order quantities (hundreds of thousands per item) enhance bargaining power and reduce procurement costs

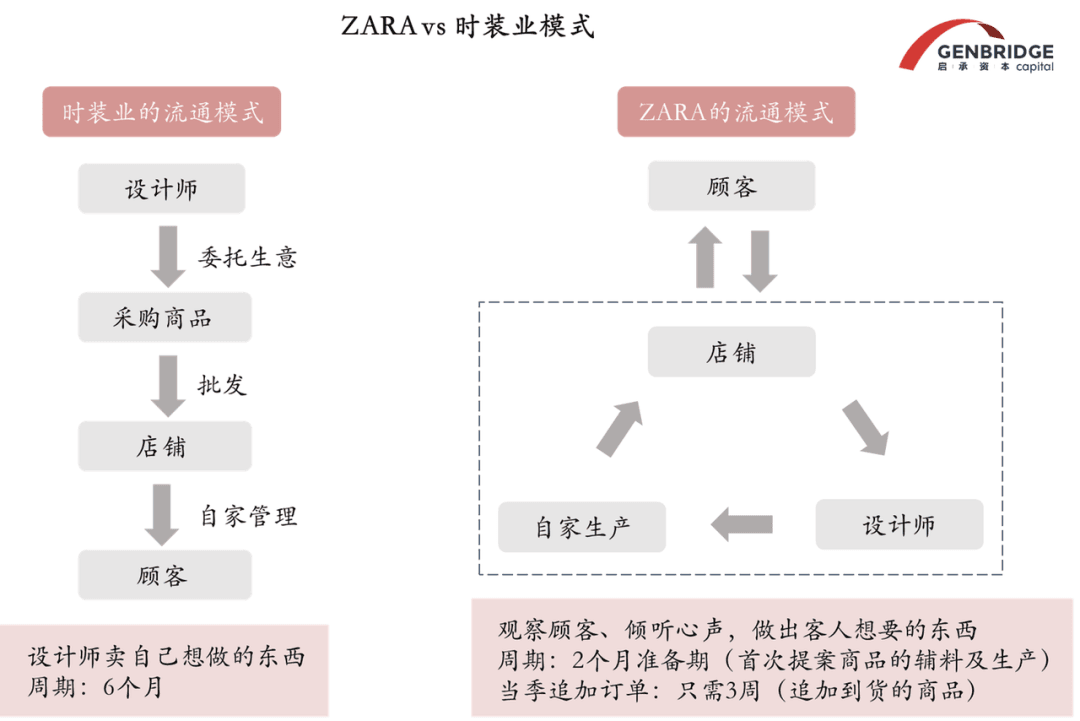

ZARA and SHEIN, which focus on fashion apparel, broke away from the "one-way quarterly feedback" model. ZARA’s used approach of “Two-Way Weekly Feedback”. ZARA’s design cycle is 2 months, but restock turnaround takes just 3 weeks.

It only manufactures 25% of its inventory at the start of the season, then adjusts based on in-store feedback. Store employees’ insights help refine designs and reorder quantities. ZARA updated its collections twice a week, on Mondays and Thursdays. By the end of each season, sales typically improve as data accuracy increases, ensuring better demand targeting.

ZARA adheres to a manufacturing-driven operational logic, championed by founder Amancio Ortega, who focused heavily on minimizing upstream forecasting errors.

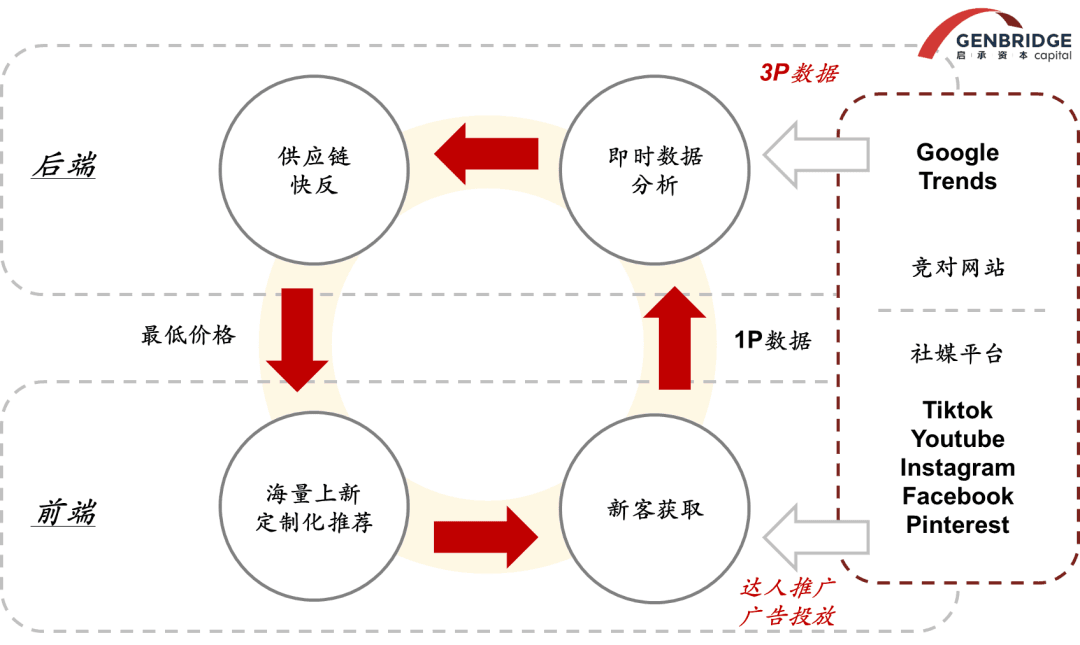

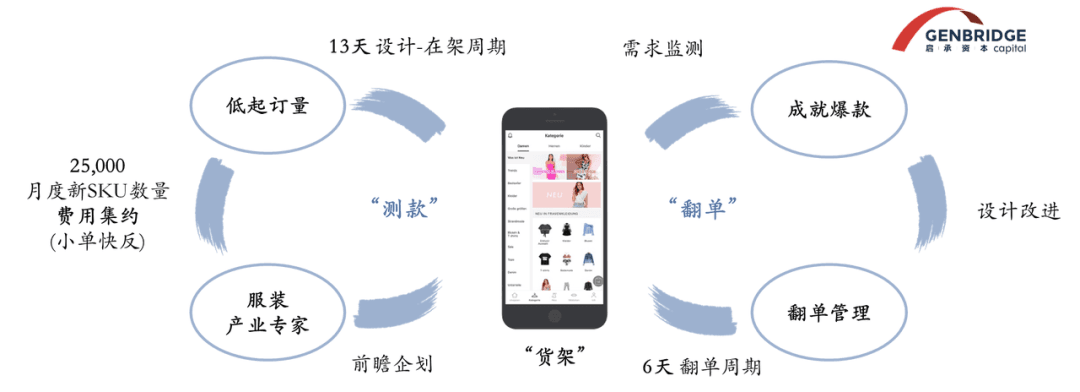

SHEIN revolutionized the industry by upgrading “fast fashion” to real-time fashion, accelerating its growth flywheel. Its “Test and Reorder” strategy, while highly effective, is capital-intensive and requires overcoming significant cold-start barriers—but it was a deliberate, long-term strategic choice.

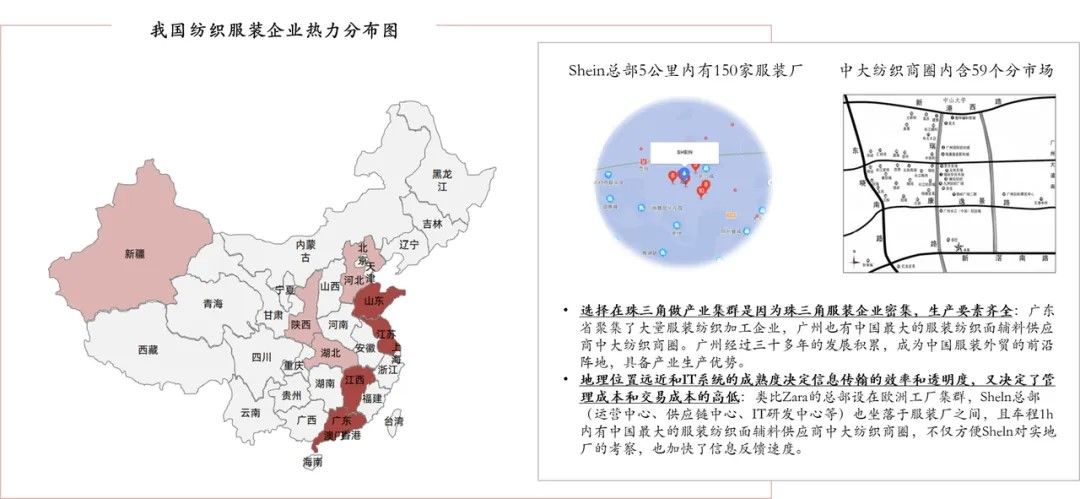

In its early days, SHEIN lacked brand credibility and could only work with small- to mid-sized factories. While these lacked scale, they were more flexible than large manufacturers, who often require orders a quarter or more in advance. This flexibility made small factories ideal for SHEIN’s rapid replenishment model.

Between 2012 and 2014, SHEIN’s “hit rate” on new products increased from 20% to 60%, validating the small-batch fast-reaction model.

SHEIN built a collaborative framework with manufacturers that included: In-house pattern making; shortened payment cycles; supportive vendor policies; integrated digital systems.

These enabled SHEIN to digitally coordinate production, forecasting, and reordering, laying the foundation for its real-time fashion engine.

- Self-Patterning: During the reordering process, pattern-making requires relatively high one-time investment but can be reused across multiple product categories. SHEIN built its own in-house pattern-making teams to reduce costs and shorten lead time.

- Shortened Payment Terms: SHEIN proactively subsidizes suppliers by taking on the cash flow burden. To ensure that factories don’t lose money on small-batch orders, SHEIN never delays payments and even offers early settlement. Additionally, it holds part of the inventory itself to relieve supplier pressure.

- Supplier Support: In early cooperation phases, SHEIN guarantees the sell-through of supplier products and even offers loans to help smaller, high-quality manufacturers build their own facilities.

- System Development: SHEIN achieves end-to-end visibility and control over the supply chain, factories, and workers via its Manufacturing Execution System (MES). Orders can either be accepted by factories or automatically assigned by the system. Required fabrics can be selected from SHEIN’s fabric library, and factories can receive real-time updates on orders based on consumer behavior.

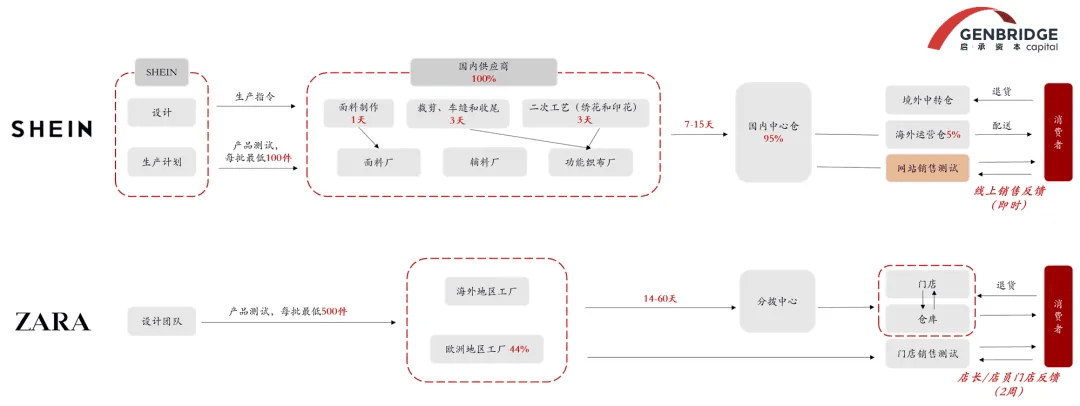

How did SHEIN improve efficiency tenfold over ZARA? Though both companies follow similar supply chain flow structures, their data transmission speed and supply chain capabilities determine their ability to launch new products and shape pricing strategies, which in turn affect end-to-end efficiency.

ZARA’s feedback loop originates from physical stores. Store managers or staff give weekly reports, which are consolidated at headquarters for replanning and reordering (2 weeks), followed by replenishment to stores (1 week)—taking about a month in total. Thus, ZARA’s feedback cycles operate quarterly and are regional/store-specific.

SHEIN’s data feedback is instant, based on real-time online sales. Once a consumer places an order, the sales data is captured immediately, enabling much faster reordering.

ZARA’s supply chain is based in Spain and benefits from a short-distance, vertically integrated model close to both production and distribution. However, compared to China's garment clusters, Europe still has a cost disadvantage. Chinese factories save around 50%–60% in labor costs and can support smaller minimum order quantities.

Operating Strategy: Precision retail system

1. Product sales and pricing strategy:

Uniqlo follows a "never out of stock" policy for its core products. As customers have clear goals when purchasing basics, stockouts create poor shopping experiences and impact retention. Uniqlo prefers overstocking rather than disappointing customers. Each Uniqlo item averages over 500,000 units sold across ~70 factories, enabling strong bargaining power and deep, flexible stocking. Excess inventory is discounted every Monday, and store managers have autonomy in markdown decisions.

ZARA focuses on “new arrivals everywhere.” As a fashion-driven brand, its customers are often inspired by in-store outfits and engage in impulse buying. Store freshness is more important than supply stability. ZARA pre-stocks about 25% of seasonal inventory and adjusts based on customer feedback. Stockouts are not feared—on the contrary, scarcity creates urgency and a "buy now or miss out" mindset.

SHEIN prioritizes "massive new arrivals" and uses real-time sales data to refine from "many" to "precise."

- FOB (designer-led): Accounts for 50% of SHEIN’s assortment and rising—this ensures exclusivity in new styles.

- ODM/OEM (buyer-led): Buyers select styles from suppliers or source from offline channels. This also accounts for 50%.

SHEIN supports designers with two systems: Trend intelligence tools, which utilizes tools like Google Trends Finder to capture fashion-related keywords and trends; and design assistance systems, which modularizes the design process—mixing and matching fabric, pattern, and style—to reduce reliance on creative inspiration and lower design error costs.

Pricing Standards of Uniqlo pioneered the "1,900 yen" pricing strategy—an impulse-buy level. Products must last at least one season of wear and washing. Despite the low price, Uniqlo maintains a gross margin of 55%, supporting sustainable growth.

ZARA prices at “half the cost of department store items” for equivalent quality, pushing customers to purchase without hesitation.

SHEIN minimizes the "trial and error cost" for consumers with ultra-low prices that offset shortcomings in quality and shopping experience. In its early days, long delivery cycles (up to 30 days) and low-quality garments hurt experience. Since 2019, SHEIN improved logistics with dedicated air freight, now delivering in 7–15 days. For example, the number of women’s hoodie SKUs on SHEIN is 100x ZARA’s, with median prices at 50% of ZARA’s.

2. Store display, expansion, and operations

Offline, there are distinct differences in the spatial configuration between UNIQLO and ZARA.

Offline store strategy of Uniqlo focuses on functional, basic wear for purpose-driven shoppers. Stores are organized by product type (jackets, shirts, tees) to allow quick, self-service shopping. “Blockbuster” items using proprietary fabrics like fleece, HEATTECH, and AIRism drive repeat purchases.

ZARA organizes stores around fashion looks and seasonal aesthetics, emphasizing mix-and-match styles and "treasure hunt" experiences. Displays include: Wall racks for trending pieces, tables for casual wear, mobile racks for seasonal essentials.

Store management of both Uniqlo and ZARA operate under a “regional manager/store manager” model. Store managers are key in gathering customer feedback. Uniqlo empowers store managers as “business operators” with autonomy over ordering and promotions. ZARA requires daily customer observations from store managers, which are fed to HQ product managers.

Online, SHEIN offers personalized interfaces tailored to each customer’s behavior, search history, and purchase data. This customization boosts repurchase rates, with repeat orders increasing 4x from 2017 to 2020.

3. Global expansion

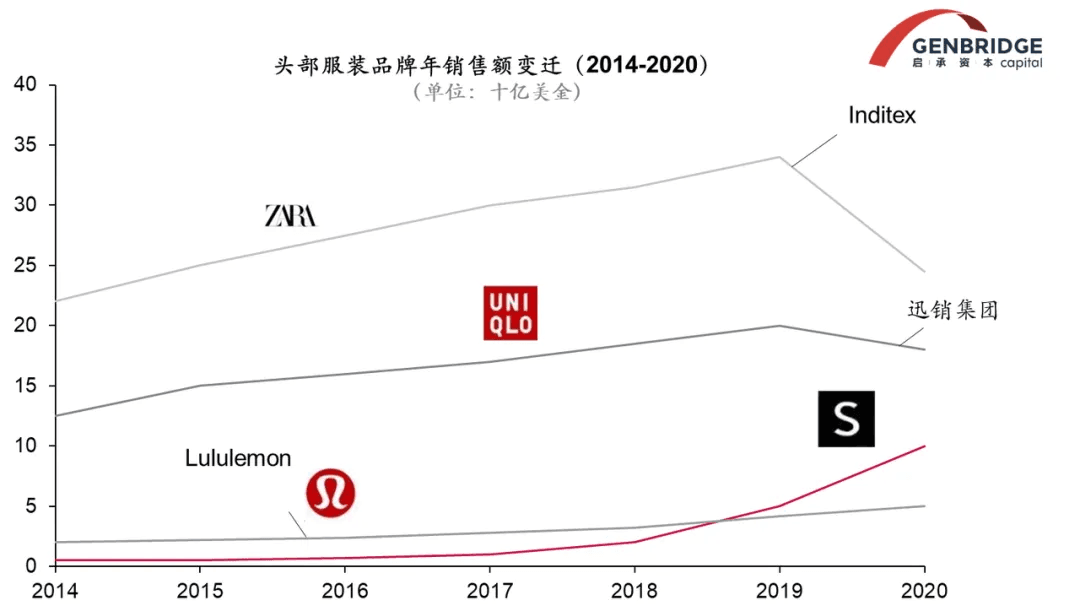

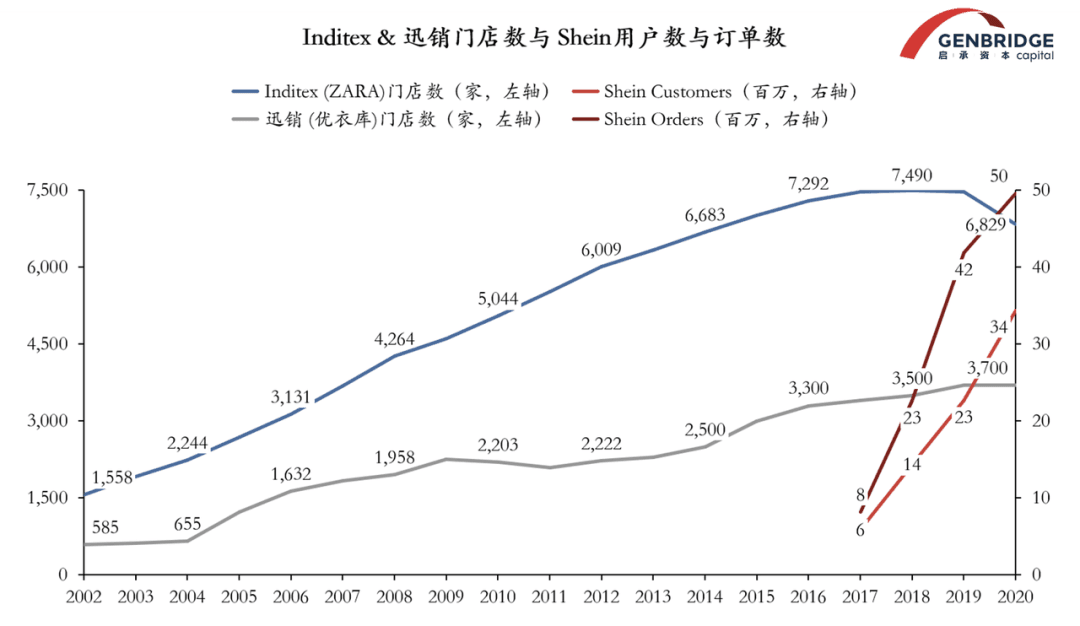

Uniqlo and ZARA expanded steadily between 2002–2015, opening 600–800 stores annually. But as SPA model competition saturated, both slowed growth significantly around 2017—the same year SHEIN gained momentum online.

Uniqlo started with small roadside stores to save rent, then expanded into shopping malls with large stores (up to 1,000 sqm) after gaining national traction and successful hits like fleecewear. Its expansion prioritizes deep regional penetration—especially Japan—before going global, with China as a key focus market.

ZARA, however, began international expansion even before fully saturating the Spanish market. Its global strategy targets major fashion cities in developed countries, where demand density is key. Stores are located in prime districts to attract fashion-forward office women.

SHEIN began international expansion as early as 2012–2014, setting up in the Middle East and Europe. Its recommendation algorithms match local preferences well, and teams plan products and marketing according to regional data.

Conclusion: In fashion, only speed wins

Fashion is like perishable goods—driven by seasonality and constant change. As category leaders over the past 40 years, Uniqlo, ZARA, and SHEIN each demonstrated high-level business model innovation, shaped by their target customers, operating systems, and supply chains.

In the future, innovation will continue to depend on improving supply chain efficiency. We look forward to more local Chinese brands leveraging the country's powerful manufacturing infrastructure to deliver better products and services to global consumers.