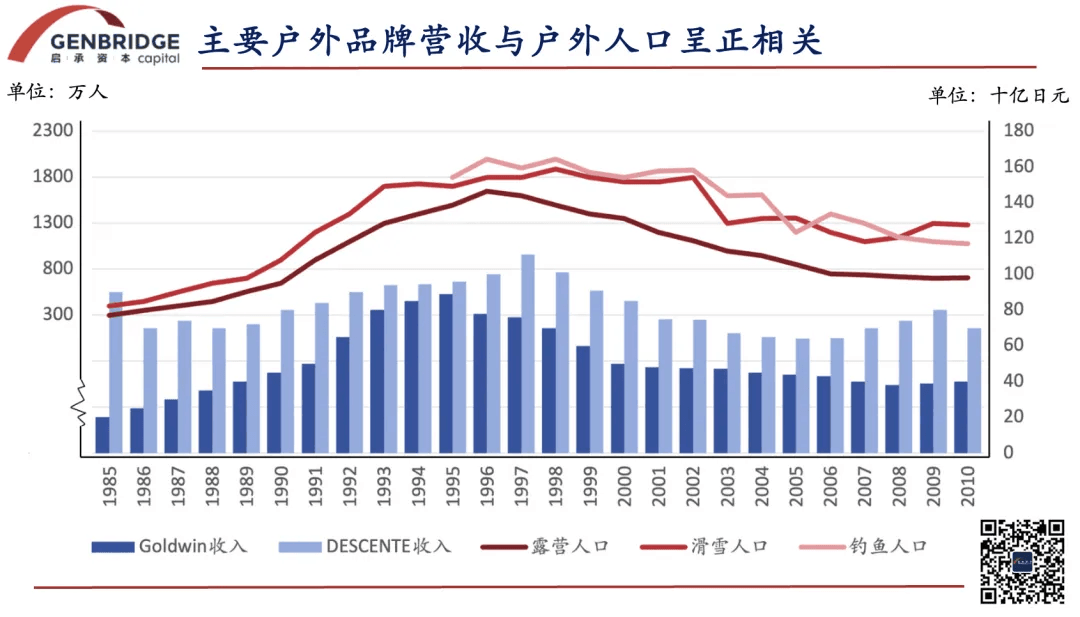

1995 marked a Waterloo year for Japan’s outdoor industry. After more than a decade of rapid growth, the nation's enthusiasm for outdoor activities suddenly plummeted, dragging outdoor consumption down with it.

Once-crowded ski resorts saw both visitor numbers and ticket prices nosedive, pushing many into financial crisis. The camping population, which had soared from 4 million to 15.8 million, dropped back to 8 million. Mountain roads that were jammed every weekend with campers became eerily deserted.

Outdoor gear, once a hot commodity occupying prime retail space, was relegated to the clearance section. The entire industry plunged into a price war, with retailers slashing prices by an average of 30%. Many once-glorious brands faced existential threats.

Goldwin, overwhelmed by excess inventory, faced a cash flow crisis and was forced to sell its headquarters and switch to rented offices. Descente saw its sales and workforce shrink by 40% by the late 1990s. Snow Peak’s revenue dropped from its 1993 peak of 2.5 billion yen to 1.4 billion yen in 1999-a contraction of nearly 40%.

"Watching the numbers fall and not understanding our consumers-how could we stay motivated at work?" lamented Fumihiro Takai, Vice President of Snow Peak.

Why did the Japanese suddenly fall out of love with the outdoors? Amid dramatic market swings, how did outdoor brands struggle to survive and weather the storm? In this article, we’ll trace the history of Japan’s outdoor industry-from its golden age to decline and eventual maturity-in search of answers.

The meteoric rise of outdoor culture in Japan

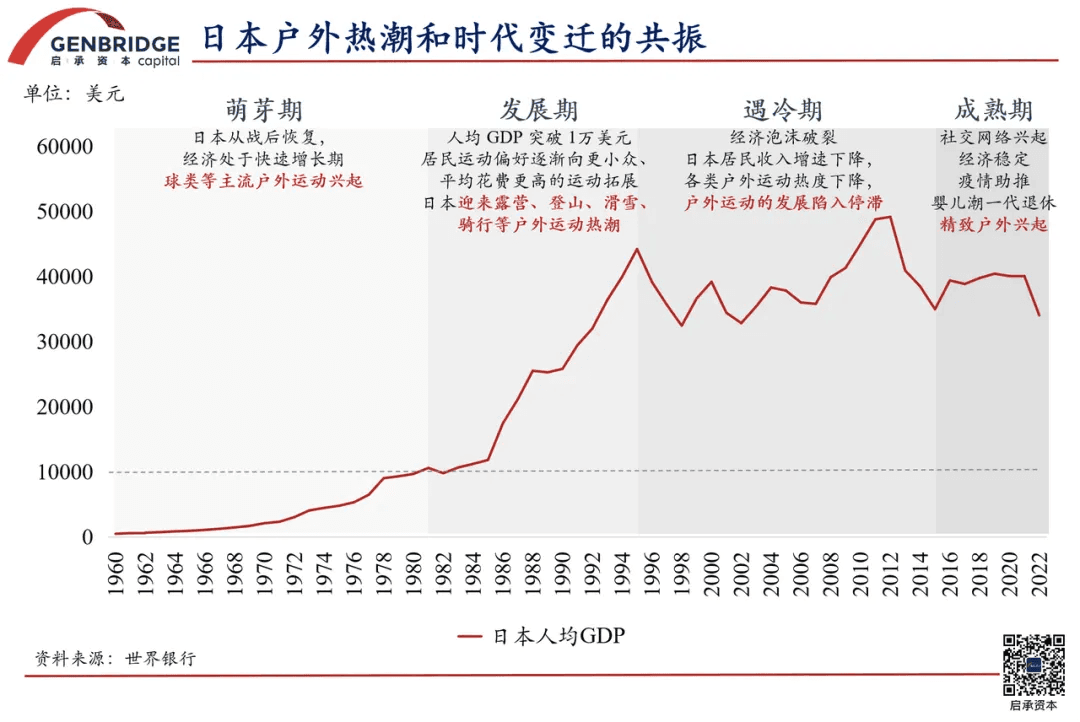

Japan’s passion for the outdoors began to stir as early as the 1960s, during the country's postwar recovery. At the time, mainstream outdoor sports like ball games started gaining popularity. At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Japan’s national soccer team reached the quarterfinals, marking a pivotal moment in the sport’s globalization within Japan.

But it wasn’t until the 1980s that Japan truly experienced a nationwide outdoor boom.

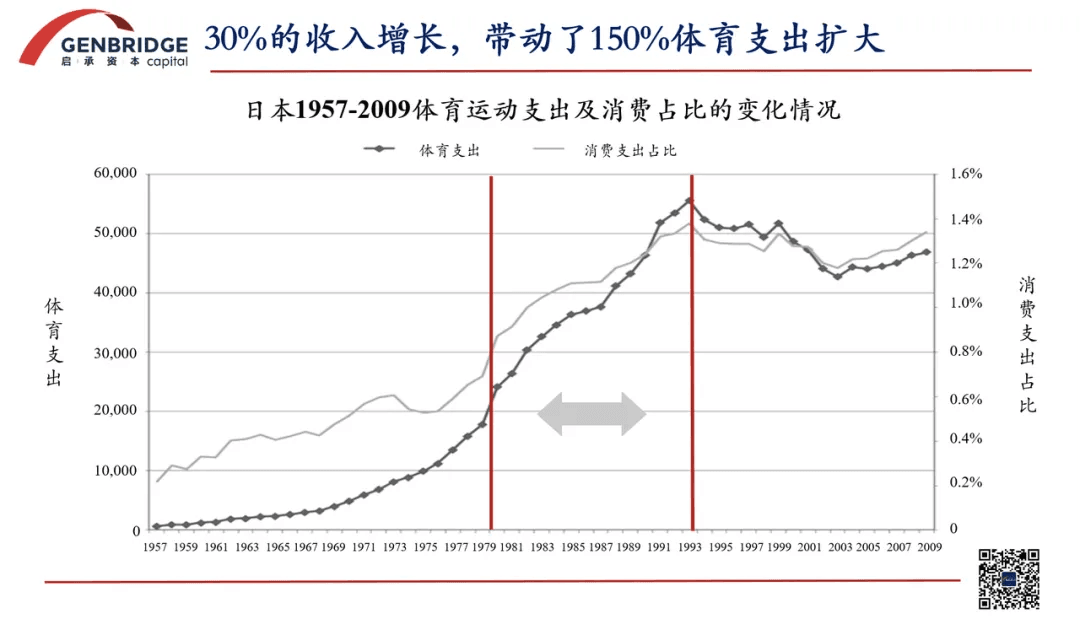

By then, Japan had ridden the wave of postwar economic growth, with per capita GDP surpassing the $10,000 mark. With more disposable income, the Japanese began to embrace costlier and more niche sports-camping, mountaineering, skiing, and cycling all experienced explosive growth.

Beyond the necessary economic foundation, several key factors fueled the sudden rise of these once-niche activities:

1. Nationwide adoption of the two-day weekend.

Starting in 1985, the average number of annual days off per worker jumped from 90 to 110 in just five years. Suddenly, Japanese people had a significant amount of leisure time.

2. Improved public transit and leisure infrastructure.

At the time, the Japanese government was investing heavily in public works to stimulate domestic demand. Throughout the 1980s, nearly 300 trillion yen was poured into public transportation and vacation infrastructure. Major projects like the Tōhoku Expressway (linking seven prefectures), the Seikan Tunnel, and new Shinkansen lines connecting Tokyo directly to major ski resorts were completed. Indoor ski domes like “Mitsui LaLaport Skiing Dome,” scenic drives like the Nanadaru Loop on the Izu Peninsula, and ski areas like Gala Yuzawa also opened during this time.

3. A cultural embrace of American lifestyle.

Postwar Japan had long nurtured an unspoken ambition to surpass the United States, and this collective mindset manifested as a full-blown cultural imitation. In 1975, the magazine Made in USA Catalog was launched, sparking a wave of Americaphilia among Japanese youth. From fashion to baseball, jazz to quirky loanwords written in katakana, American culture became synonymous with being trendy.

As a result, outdoor activities beloved by Americans-like hiking, skiing, and cycling-naturally captured the Japanese imagination and became go-to leisure pursuits during the 1980s.

More holidays, better infrastructure, and a frenzy for all things trendy-each factor acted as a lever, collectively catapulting the outdoor industry skyward. From 1979 to 1993, Japan's overall consumer spending grew by only 30%, but the sports market expanded by a staggering 150%.

Japan’s outdoor market entered an unprecedented golden age. Countless brands rode the wave, and “outdoor style” came to dominate fashion trends for the next two decades. Homegrown labels like Montbell, Goldwin, Descente, and PHENIX all rose to prominence during this era.

American brands also enjoyed a cult-like following. Trend magazines such as POPEYE regularly featured special issues dedicated to Patagonia, teaching readers how to style their gear. L.L.Bean, the quintessential New England brand, became wildly popular in Japan. Its canvas totes and Bean Boots turned into must-haves, and through catalog-only mail orders, the Japanese market alone contributed nearly 30% of L.L.Bean’s revenue.

But the rise of these brands went beyond mere commercial success-it ignited a cultural revolution in Japan’s outdoor scene.

Montbell’s founder, Isamu Tatsuno, scaled the north face of Switzerland’s Eiger at age 21, becoming the youngest climber in history to do so. Patagonia’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, was already a legendary rock climber and environmental advocate. These founders, with their near-mythic backstories, became spiritual icons to Japanese outdoor enthusiasts. They opened shops at the foot of mountains and ski resorts, channeling ideals of self-transcendence and reverence for nature into every corner of the outdoor experience-and in return, funneled sales revenue steadily back to headquarters.

At the time, overseas brands were unfamiliar with the Japanese market, allowing local companies to profit enormously by securing distribution rights. Montbell acquired exclusive rights to distribute Patagonia in Japan, with the latter accounting for 25% of Montbell’s revenue. Descente derived 83% of its income from sub-brands or licensed labels. Goldwin, which held the rights to The North Face, saw its performance skyrocket-company revenue tripled in a decade, rising from 26 billion yen to 80 billion yen.

By the 1990s, Japan’s outdoor enthusiasm reached its peak. The ski equipment market surpassed 400 billion yen in 1991. The number of campers nationwide had quadrupled. The combined market for mountaineering and camping gear topped 10 million units.

But this passion proved to be more of a fleeting crush, intoxicated by the euphoria of Japan’s economic bubble-exhilarating in its rise, and just as dizzying in its fall.

The other side of the frenzy

Looking back at the outdoor market's most prosperous years, the seeds of its downfall were already being sown.

In 1987, the romantic youth film Take Me Out to the Snowland became a box-office hit. The following year, the number of skiers surged by 35%, exceeding 15 million. At the time, there was even a saying: “If you can’t afford Roppongi (Tokyo’s upscale district), take her skiing.” Young couples dressed to impress amid the snowy slopes, turning ski resorts into de facto fashion runways.

These phenomena reveal a deeper truth: the explosive growth of Japan’s outdoor market wasn’t driven by a deep-rooted embrace of the outdoor lifestyle, but rather by a herd mentality chasing the latest trend. As an imported cultural product, outdoor recreation was essentially a form of novelty consumption-easily replaced by newer forms of entertainment.

As the renowned designer Eiko Ishioka once put it: “The Japanese are like pickles steeped in American culture-but at their core, they’re still East Asian pickles.”

That moment of reckoning came quickly.

In 1995, Japan’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) dipped below zero for the first time, signaling the spread of the post-bubble economic downturn. People began tightening their belts and cutting back on spending. Costly outdoor activities were among the first to go-deemed non-essential expenses. This triggered the dramatic industry collapse described at the beginning of this article.

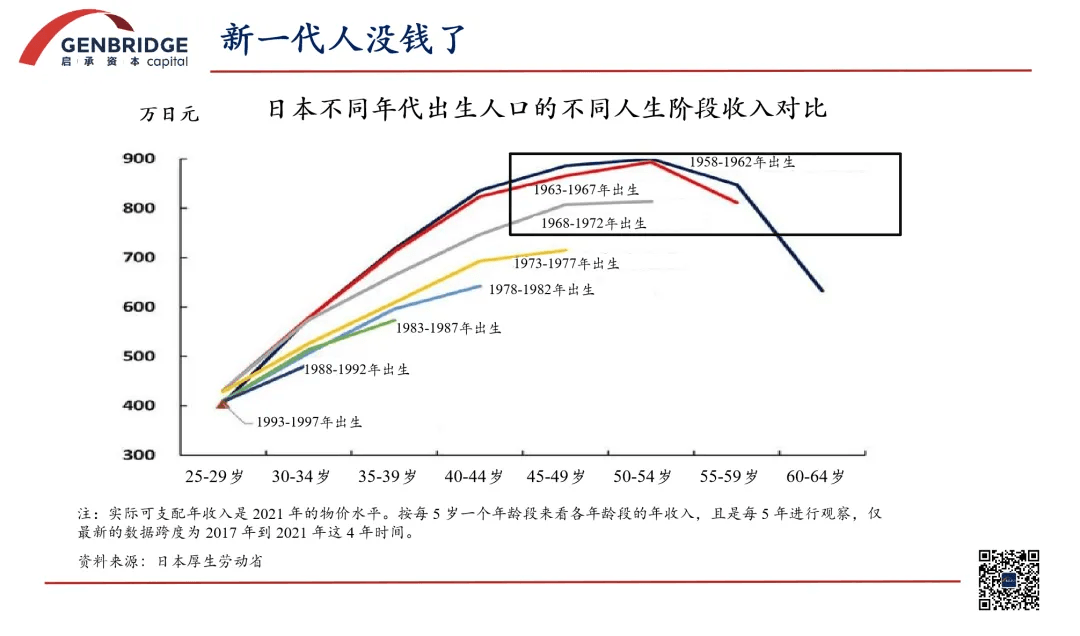

Decades of economic stagnation created a generational gap in outdoor participation. The new generation of young people, earning less than their parents, gravitated toward staying at home, watching TV, and playing video games. As a result, the outdoor consumer base began to shrink and age. Whether it was skiing, camping, or fishing, these seemingly distinct consumer booms were actually just the same group of people aging through different phases of life.

Against this backdrop, cyclical fluctuations in the market became all but inevitable.

In contrast, the situation in Europe and North America presents a completely different picture.

Over the past 20 years, the outdoor sports participation rate in Europe and North America has consistently remained above 50%, with the industry growing steadily. For Western consumers, spending weekends in nature with family and friends-much like how the Japanese enjoy soaking in hot baths-is a lifestyle passed down through generations.

This difference primarily stems from deep-rooted social and cultural distinctions. Since the Age of Discovery, the "spirit of adventure" has been embedded in Western cultural identity. Modern outdoor sports also originated from scientific expeditions in the Alps-cultural soil that Japan lacks.

However, beyond this stark contrast lies another key factor: differences in vacation systems.

At the time, Japanese holidays were concentrated on weekends and public holidays, resulting in a pulsed flow of people with clear peaks and troughs. In contrast, many European and North American countries had already implemented widespread annual leave systems, allowing workers to enjoy a month-long vacation with ample time to explore nature. In other words, Europeans and Americans go on vacation-Japanese people merely go on day trips.

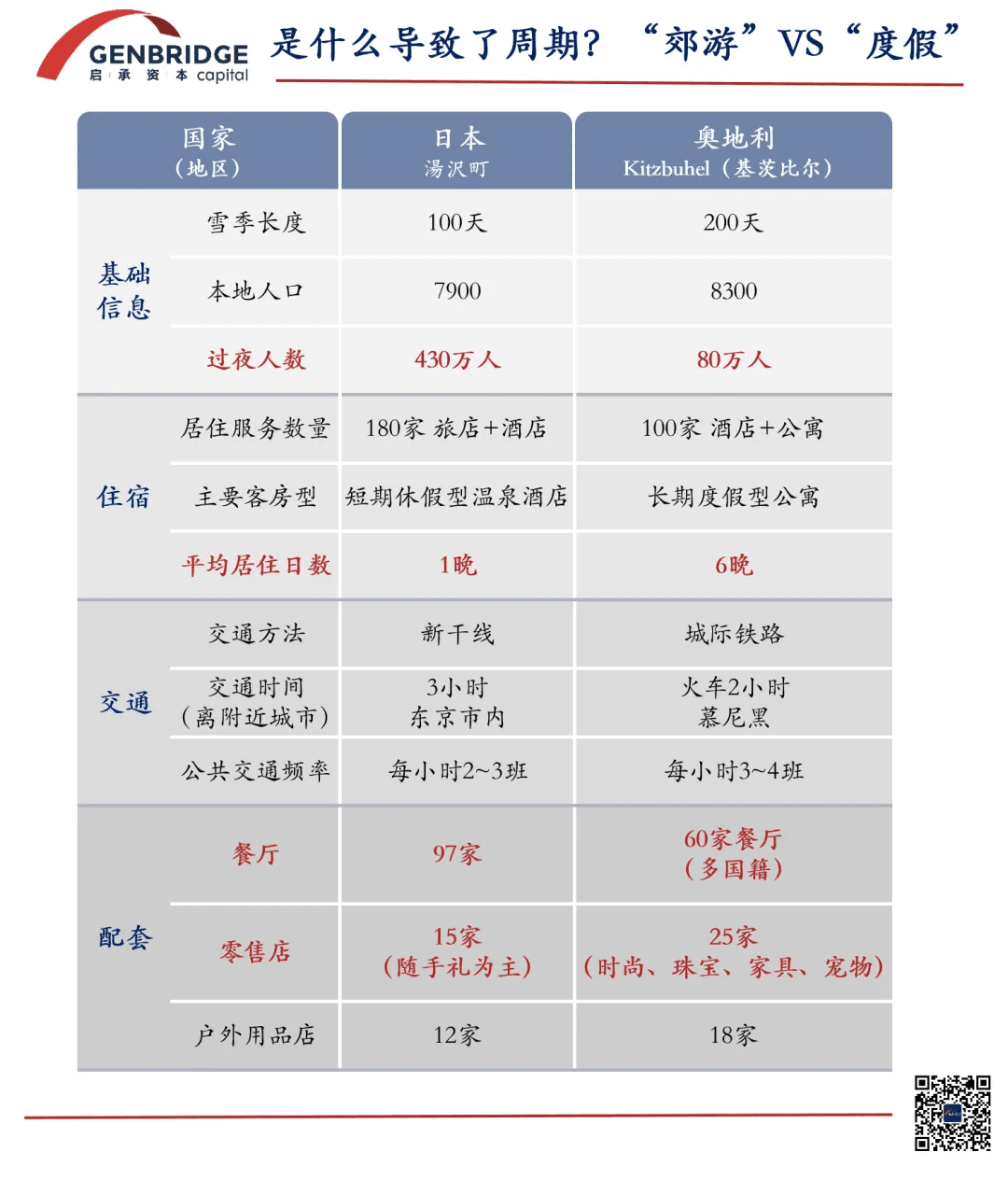

The chart below compares facilities in Yuzawa, Japan, and Kitzbühel, Austria. Though both are renowned ski destinations, the disparity in infrastructure reveals the essential differences in outdoor consumption.

In Austria, ski resorts are typically surrounded by long-stay vacation apartments, with visitors staying an average of six nights. Retail offerings meet daily living needs, creating the feel of a fully functional town. In contrast, Japanese ski resorts resemble sightseeing destinations, where most shops sell souvenirs and tourists usually stay only one night.

Different vacation systems give rise to different lifestyles. The calm of a gentle breeze, the grandeur of mountain peaks, the beauty of living creatures-Japanese consumers rarely have the opportunity to truly incorporate these experiences into the rhythm of their daily lives. After a brief stay, they must rush to catch the Shinkansen and return to the hustle of the city.

In this kind of tempo, the outdoors can only ever be a fleeting pause in life.

A survival guide for counter-cyclical time

Massive market fluctuations swept through all segments of the outdoor industry like a tsunami.

Under this impact, many once-prominent brands met their demise. Camping brand OGAWA, mountaineering brand MONTURA, and ski brand PHENIX all quietly exited the stage. Even Yamaha, which once crafted snowboards from its high-quality instrument materials, had no choice but to sell off this unpromising line of business.

In this outdoor industry survival game, brands that are closer to consumers and able to swiftly adapt their product strategies-namely, retail channel brands-have shown greater resilience.

Take Alpen, a retailer founded in 1972, as an example. Leveraging its position as a retailer, Alpen responded to market shifts by adjusting its business model and product selection. In the 1990s, its ski-related revenue plummeted from 93 billion yen to 20 billion yen. Alpen decisively shut down its specialized ski stores and pivoted to selling golf equipment and general sports goods. Over the span of 30 years, Alpen successfully transformed itself from a single-category ski retailer into a comprehensive outdoor retailer.

As for product brands, they had no choice but to grit their teeth and find ways to survive within their existing segments. The strategies adopted by companies that made it through that period generally fell into three categories: competing on functionality, competing on fashion, and competing on customer loyalty.

Competing on functionality means pushing technical innovation to the extreme. In outdoor activities, people are always accompanied by risk-cold or damp conditions can be fatal. Functionality is the core value of professional outdoor gear.

Montbell, mentioned earlier, is a prime example of a brand that excels in functional innovation. Its slogan, “Function is Beauty,” reflects the philosophy of its founder, Isamu Tatsuno: outdoor gear should prioritize functionality, and design should never compromise it. As an experienced outdoor expert, Tatsuno took full advantage of the evolving fiber technology at the time and translated it into products.

Montbell was one of the first brands in Japan to introduce GORE-TEX technology. Every time there was a breakthrough in fabric innovation, Montbell was quick to incorporate it into its outdoor gear. Beyond that, Montbell also developed its own coatings, techniques, and proprietary materials, holding patents for several technologies including Hydro Breeze, Polkatex, and ClimaPlus.

Even Montbell’s store staff are like walking encyclopedias of outdoor fabrics. At any Montbell store, a customer simply needs to describe their outdoor destination, and the staff can instantly recommend a complete outfit tailored to the season, temperature, and terrain-balancing both functionality and cost performance. This has earned Montbell a firm foothold among hardcore outdoor enthusiasts.

In contrast to competing on functionality, other brands chose to compete on fashion, liberating outdoor apparel from its purely utilitarian roots.

Even as the number of outdoor consumers declined, the trend of outdoor-inspired fashion showed no signs of slowing down. With the support of fashion magazines and select shops, outdoor wear merged with Japanese workwear and military aesthetics to become part of everyday urban style-eventually evolving into a signature Japanese fashion trend known as Yama Style.

A key figure in this movement is designer Eiichiro Homma. His collaboration with Goldwin to create The North Face Purple Label set the tone for this urban mountain aesthetic-replacing baggy traditional cuts with a more tailored silhouette, and favoring muted tones to create visual contrast between pieces of different styles.

“What we do is make the brand more suitable for urban wear, without compromising its original core values,” explained Homma.

Today, pairing a technical jacket with a skirt or hiking boots with dress pants has become commonplace-outdoor wear has become the most accessible fashion choice for urban youth. Amid shifting fashion trends, the industrial chain behind outdoor brands has also quietly evolved.

First, there has been a shift in decision-making power. As "style" becomes increasingly important, creative directors have become the driving force behind upstream production. Next is the change in retail channels: in the 1990s, most outdoor brands were sold through category-specific retailers (similar to Sanfo Outdoor), but today, most have adopted a direct-to-consumer urban store model. To better cater to urban customers, select shops like Beams and United Arrows have risen to prominence, translating "outdoor" into "urban" and placing outdoor apparel on equal footing with designer fashion.

The third strategy is competing on customer loyalty-using refined community and membership management to retain customers and maximize LTV (lifetime value).

According to the Diderot Effect, when people purchase one new item, they often buy additional items to match it, eventually changing or upgrading their entire lifestyle. The core question for outdoor brands in membership management is how to tap into this psychology and turn consumers into ecosystem users. Their solution lies in building stable connections between brand and user-and among users themselves-while offering genuinely valuable benefits.

Take Montbell again as an example. Outdoor activities are inherently risky and better suited for group participation, making them fertile ground for sticky communities. Group leaders act as influencers for newcomers, making it ideal for building brand influence and customer loyalty. Every year, Montbell organizes over 6,000 outdoor challenge events-including hiking, kayaking, rafting, and more-with nearly 60,000 participants.

Most general commercial insurance policies explicitly exclude high-risk outdoor activities. Montbell fills this gap by offering a wide range of outdoor activity insurance plans, covering everything from basic outdoor recreation to high-risk mountain climbing-directly addressing a major pain point for outdoor enthusiasts. Today, Montbell has nearly 2 million members, with membership-driven sales contributing over 30% of its total revenue.

Another notable case is Snow Peak. After switching to a direct-to-consumer model in the early 2000s, Snow Peak designed its stores to resemble campsites, offering users a tangible experience of the brand’s lifestyle. Its annual Snow Peak Way event has become a festival where staff and customers camp together. Exclusive member products, lifetime after-sales service, and efficient repair offerings have all strengthened customer loyalty. These strategies have gradually led consumers to internalize the camping lifestyle that Snow Peak promotes.

The companies that endured the downturn were tempered in the crucible of adversity. Entering the 21st century, they emerged with stronger, more well-rounded capabilities, firmly rooted in Japan and expanding globally. They became evergreen brands in the global outdoor industry-and found their way into business school case studies.

Conclusion

The cyclical fluctuations of the outdoor consumer market are not unique to Japan.

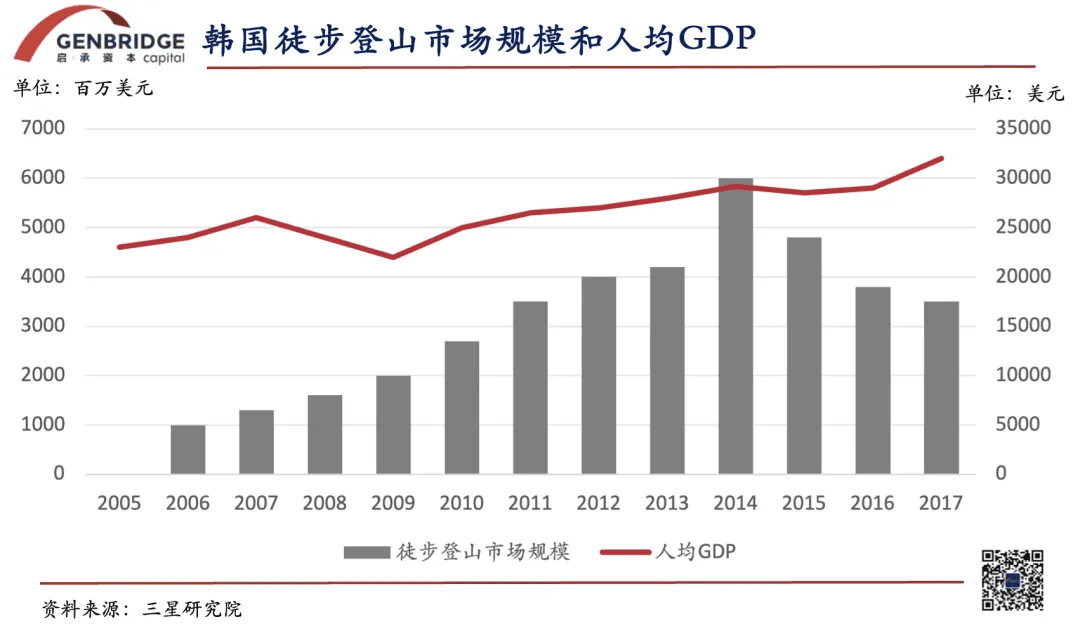

The “rapid rise followed by a sharp decline” pattern also occurred in South Korea. After the country’s per capita GDP surpassed $20,000 in 2005, the outdoor hiking market grew from $800 million to $6 billion within a decade. During this period, numerous brands and investors rushed in, leading to excessive supply-side expansion. By 2017, the outdoor bubble burst and the market contracted to $3 billion. Some brands exited or transformed, and even leading players like K2 Korea and Black Yak experienced a sharp drop in sales.

However, regional differences in demographics, market size, and supply-side competition intensity mean the effects of the outdoor market cycle vary. For example, in Taiwan, although the outdoor market also experienced booms and retreats, the overall fluctuation was relatively moderate. Even after the hype faded, the market remained above its previous baseline-representing a growth-oriented cycle.

Into the 2020s, fueled by social media and accelerated by the pandemic, outdoor activities became trendy once again. Restrictions on long-distance travel pushed people toward nearby outdoor options, and social media further sped up the transformation of lifestyle habits.

As a result, mature outdoor markets like the U.S. and Japan saw a clear resurgence. In the U.S., the number of outdoor activity participants increased by 10 million in just two years. In Japan, young people rekindled their passion for nature-“solo camping” (ソロキャンプ) was even selected as one of the top 10 buzzwords of 2020. The number of camping-related companies soared by 227%, and campsites were often fully booked during holidays.

Meanwhile, China’s outdoor market began playing out a story strikingly similar to Japan’s in the 1980s. In just five years, sports like ultimate frisbee, camping, and skiing rose in waves, each becoming a social media sensation in turn.

New niche brands in segmented outdoor apparel and footwear categories quickly gained traction, outshining traditional mainstream sports brands. Nike and Adidas both stumbled in the Chinese market, while high-end international brands like Lululemon, Arc'teryx, and Salomon raced ahead-turning yoga pants, technical jackets, and hiking shoes into social status symbols for urban professionals. Domestic brands also had their moment: niche players like Mobi Garden and Kailas broke into the mainstream, and legacy brand Camel successfully made a comeback.

From Seoul to Taipei, Tokyo to Beijing, the outdoor consumption wave continues to surge restlessly-always in search of its next landing point.