Supermarkets across China are undergoing retail transformation, what will the endgame look like?

Snack chain stores are expanding rapidly, is there still room left in the market?

Is developing private-label products a mandatory course for retailers?

China’s retail industry is currently undergoing a profound generational shift. Retsail channels are evolving at an accelerated pace, and new formats and solutions are emerging one after another. The old balance has been disrupted, and a new equilibrium has yet to be established. In the midst of this transformation, people are eager to find answers to these pressing questions.

Recently, Victor Zhang, founding partner of GenBridge Capital, was featured in an exclusive interview with China Entrepreneur Magazine《中国企业家》, where he shared GenBridge’s perspectives on the evolution of China’s retail landscape.

According to Victor, emerging retailers have successfully adapted to market changes through buyer-driven strategies such as transformation and reform, category management, and production-distribution alliances. As categories are recombined, new retail formats will continue to emerge and offer the greatest opportunities for the future of the retail industry.

Below is an edited excerpt of the conversation between China Entrepreneur and Victor Zhang.

“Pangdonglai-inspired transformation” is just a symbol in the era of channel reform

China Entrepreneur: From last year to this year, the “Pangdonglai-inspired transformation” has become a buzzword. What significance do you think this has for the retail industry as a whole?

Victor Zhang: In China’s retail market, various formats of different scales coexist, such as small, medium, large, and extra-large stores. The current wave of transformation reflects the shift of large-scale formats in China from seller-driven to buyer-driven solutions.

Today, the supermarket sector is undergoing a clear bifurcation: around 80% of traditional stores are shrinking due to their inability to adapt to the new environment, while newly opened stores—including those that have undergone Pangdonglai-inspired transformation and other emerging retailers—are thriving with strong performance. At the core, it’s because these stores have embraced category management and buyer-centric strategies, enabling them to keep pace with market changes. This highlights the importance of buyer thinking and buyer-oriented solutions. Pangdonglai-inspired transformation is merely the market's current spokesperson for this transformation.

China Entrepreneur: Have you visited any stores after undergoing the transformation? In what aspects have they improved compared to before?

Victor Zhang: Yes, I have. The processing areas are the easiest places to demonstrate and unlock value in service-heavy formats, such as bakery and deli sections. These have seen significant improvements.

In addition, the category structure has been well-adjusted. Pangdonglai has become more professional in its product selection, presenting products from the consumer’s perspective and clearly explaining the pros and cons, thereby raising the industry standard.

I also believe that this cost structure and format can only serve specific consumer groups and needs, and there’s an inevitable ceiling to its market share. Not all stores are suitable for the Pangdonglai-style transformation. As a result, many supermarkets will still need to close, but for those that are suited to adjustment, their per-store productivity will increase, unlocking greater vitality.

China Entrepreneur: Now that more and more large supermarkets are embracing “transformation,” could this lead to a new wave of homogenization? Has transformation become the only solution?

Victor Zhang: Retail is inherently a local business, serving a specific surrounding population. When too many similar stores cluster in one area, market forces naturally drive differentiation. The first approach is stratification. For example, stores can position themselves as premium, mid-range, or budget. In Hong Kong, for instance, a single supermarket brand often operates at least three different tiers to cater to consumers at various levels. This kind of stratification allows the brand to open stores densely even within limited spaces.

In addition, segmentation around target demographics is another way forward. In my view, market segmentation is a long-term direction for China’s retail development. By catering to different consumer groups based on age, family structure, and other characteristics, retailers can create meaningful differentiation.

China Entrepreneur: Pangdonglai rose to fame largely because of its consumer-friendly approach. Do you think its influence is pushing more retail companies today to become “better to consumers”?

Victor Zhang: Behind every act of “being good” to consumers, there’s always a cost—and resources are limited. So from a business perspective, service costs should be invested where they matter most to the consumer.

Pangdonglai’s customer base places a high value on the sense of on-site preparation and attentive service. This model is somewhat similar to the restaurant industry, where service quality heavily affects the dining experience. If service is poor or staff morale is low, customers instinctively perceive the food quality to be poor as well.

In contrast, retail formats that sell standardized products interact with customers mostly at checkout. Beyond that, there are relatively few touchpoints. In a well-organized store, what customers may value most is a quiet, uninterrupted shopping experience.

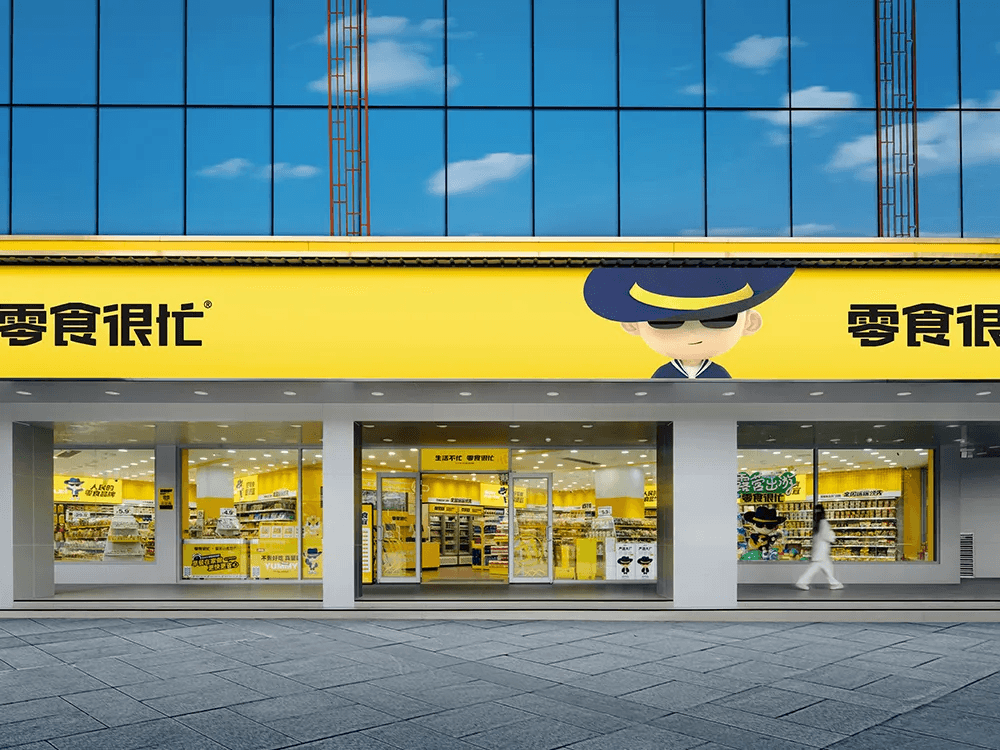

Take, for example, retail formats like Snack Is Busy. Their focus is on display, music, lighting, and the overall visual and customer service experience. These elements enhance the consumer’s mood and shopping enjoyment. All of this counts as “service,” though it takes a different form. So for different formats, “being good to the customer” manifests differently. Given today’s resource constraints, such goodwill needs to be delivered with precision—right where it makes the most impact.

China Entrepreneur: How do you view Yonghui Superstores’ move to eliminate intermediaries and adopt a “bare-price” direct sourcing model? Is this a broader trend?

Victor Zhang: Yes, it’s a major trend. The current retail transformation reflects a reshuffling of industry roles. In the past, brand owners dominated the distribution system through multi-tiered structures like dealers and distributors. But now, as retailers grow stronger, they are no longer willing to accept this traditional division of labor. They’re increasingly focused on category management and aligning precisely with consumer needs, rather than relying on generic products from big brands.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that all intermediaries will vanish. But their roles will change significantly. In the future, intermediaries will need to earn service fees by providing value-added services. If they want to profit from price margins, they must create value that justifies those margins. For instance, import agents who handle brand promotion and market penetration can still earn a fair margin based on their expertise. However, intermediaries that only provide basic warehousing or logistics and expect to profit from that alone—this model is unsustainable.

In Yonghui’s case, direct sourcing is one way of initiating management reform. By focusing on direct sourcing of key products, they’re addressing the most critical aspects of their operations first. But this doesn’t mean that all products will be sourced directly.

Discount snack stores still have room for hundreds of thousands more locations

China Entrepreneur: In 2019, you first discovered Snack Is Busy (“零食很忙”), and by March 2021 you became one of the first-round investors. How did you come across the project, and what led you to focus on it?

Victor Zhang: We've always had a strong focus on retail. Drawing from our background, we proposed that the future of retail would move toward “localization, discounting, and manufacturing integration.” We believed that the first wave of change in China’s retail landscape would be toward localization—large supermarkets, which are inefficient and unable to fully meet consumer demand, would gradually be replaced by category-specialized stores.

Following that logic, we explored areas like fresh produce, ready-to-eat foods, and frozen goods. Eventually, we came across Snack Is Busy in Changsha. What we saw was a concept rooted in buyer-driven logic which aligned perfectly with our investment philosophy.

China Entrepreneur: What was your strongest impression of Zhou Yan, the founder of Snack Is Busy? From 2019 to 2021, what were you observing or waiting for?

Victor Zhang: Zhou Yan struck me as someone who is deeply committed to products and to serving consumers well. In his management practices, he actively works to eliminate corruption, simplify procurement processes, and prioritize timely payments to suppliers. Many of his principles weren’t learned from Western brands like Costco or Aldi, but were driven by common sense and a clear vision. Yet, his thinking aligns very closely with the conclusions we’ve reached through theoretical analysis.

Initially, he wasn’t focused on fundraising. Most of his energy went into building the company itself. Only after the foundation was solid did he begin seeking investment. So during those two years, we were both observing and waiting for him to be ready for funding.

China Entrepreneur: How much room for growth do you think still exists in the discount snack store market?

Victor Zhang: First, in terms of the current format, the number of viable stores depends on the size of the consumer base per product category and the relevant consumption scenarios. Based on that, I estimate the ceiling for this format is in the range of several hundred thousand stores nationwide. From another perspective, while retail may appear slow-changing, it’s actually always evolving. The same goes for the discount snack industry—it’s continuously refining and expanding into new scenarios and needs. So I believe this format still has the potential to scale into hundreds of thousands of stores across China.

China Entrepreneur: Why are discount snack formats increasingly shifting toward discount supermarket models? Will multi-category expansion become the next major competitive dimension?

Victor Zhang: discount snack formats essentially cover a few core consumption scenarios:

- Inside the home, they address the dining table, tea table, and kitchen.

- Outside the home, they cater to mobile settings, offices, schools, etc.

Currently, the most important scenario is still the home coffee table, followed by the dining table. The format is gradually expanding to more external settings, but shifts in core consumption scenarios are usually slow and require long-term operational stability. Expansion typically comes through increasing product categories to meet broader needs.

Therefore, while the evolution of the discount snack format will definitely lead to overlaps with other retail formats, those overlaps will likely account for no more than 20% of each format’s revenue.

I don’t believe category expansion alone will be the next battleground. Retailers are always tweaking and optimizing their product categories. These day-to-day changes often go unnoticed by the general public. It's only when they overhaul an entire store format—like changing the store layout or model—that the shift becomes more visible to outsiders.

Private labels products are a required course for retailers

China Entrepreneur: Snack Is Busy has also begun pushing private label products. Why do channel-based retailers ultimately choose to develop their own private labels?

Victor Zhang: While the short-term motivations for launching private labels may vary, the long-term goal is inevitably to increase sales—and that’s entirely reasonable. But at its core, private label development is really about category management. There are always niche demands that existing market products don’t satisfy. To offer consumers better category solutions, retailers have no choice but to engage in private label development.

In China, the foundation of private label growth is still grounded in the logic of product development. The question isn’t simply “should we launch private labels?”—it’s about identifying, along the consumer’s decision-making journey, which touchpoints should be met through in-house brands and which should be met using external brands.

In my view, private label is a mandatory course for retailers. It may not always outperform national brands, but avoiding it altogether is not viable. In the long run, private labels benefit not only consumers, but also contribute to industry progress and societal efficiency. That’s why GenBridge is deeply committed to this area, including direct investment in manufacturing facilities.

China Entrepreneur: What kind of factories are we talking about here?

Victor Zhang: These are supportive factories, designed to meet diverse consumer needs across product categories horizontally and to go deeper into upstream manufacturing vertically, working closely with retailers to co-develop custom products.

Our investment in factories is driven by the need for deep post-investment collaboration. During this transformation phase in the industry, high-quality factory resources are scarce. So we’ve chosen to create model factories. Their key value lies in development capacity—the ability to rapidly create products aligned with retail needs and ensure quick inventory turnover.

For example, we’re building a fresh food factory focused on short shelf-life products like rice balls, sandwiches, and baked goods, with fast turnover. These supportive factories will become increasingly attractive to retailers in China.

China Entrepreneur: What kind of production scale do these factories operate on?

Victor Zhang: Around 300 million RMB in output value. Since they’re regional factories, we typically build 1–2 per region.

China Entrepreneur: Many private label brands are now trying to move beyond their original sales channels, though it’s a difficult process. What’s your take?

Victor Zhang: That kind of expansion is more of an outcome, not the original intent. Private labels were created from a category management perspective—once the market shifted to a buyer’s market, retail moved from brand-driven to channel-driven operations focused on managing product categories. The purpose of this shift was to better serve the retailer’s own customer base.

We assume that consumer needs can all be quantified, like price, packaging, size, taste, and quality. Private labels exist to serve these precise needs within a specific channel. If consumer needs happen to overlap across multiple channels, private labels may naturally expand. But such expansion is mostly accidental, not strategic. After all, the original purpose was to meet internal channel needs.

The difference between brand-building logic and private label logic is this: when building a national brand, your own channel is just an incubator—you launch from there and gradually expand, seeking broader commonalities across the market. In contrast, private labels focus on internal channels and customers, emphasizing differentiation. To put it simply, building a national brand is about finding common ground, while private labels are about carving out distinctions.

Finding certainty in compound growth

China Entrepreneur: You've experienced the ups and downs of the consumer goods cycle, including the cooling-off of the “new consumption” wave around 2021. Looking back, what are your reflections?

Victor Zhang: I think the term “new consumption” that everyone was buzzing about around 2021 might have been a VC-created concept.

If we look at some markers, the idea behind “new consumption” initially emphasized rapid growth via traffic acquisition—growth that heavily relied on internet tools and platforms, often needing massive capital investment. Many of these brands expanded by burning cash. In essence, they borrowed the startup playbook of internet platforms and tried to apply it to consumer brands—but this doesn’t really fit.

In internet business, the “winner-takes-all” model means the top player can command 80% of the market. But in consumer goods, concentration rarely reaches that level—the leader typically holds only 20% to 30%. So applying VC investment strategies to a non-VC-growth industry like consumer goods was a misstep.

China Entrepreneur: What types of projects are you most focused on now?

Victor Zhang: In chain operations, we’re increasingly focused on category specialization and format combinations. For example, merging coffee with baked goods, or integrating braised snacks with other categories. Food and beverage scenarios still dominate consumer life. So these new combined formats are where we see major opportunity.

We’re also very interested in the “3-in-1 model”—product, store, and online integration. This model enables franchising, private label sales, and online-to-home or self-pickup operations. It’s more resilient to economic cycles and external shocks, and tends to be highly efficient—exactly the kind of retail model we like.

Specifically within this model, we’re looking at beauty and skincare sectors. These categories may evolve into hybrid formats that combine products with services. Services will play an increasingly important role in the value chain—but because they’re hard to standardize, products can serve as a scalable base, while services drive differentiation. A “product + service” chain model is likely to perform very well.

China Entrepreneur: In the restaurant chain market specifically, what traits do you look for?

Victor Zhang: Two things: Short menus and balanced carbohydrate-to-protein ratios.

The carb-protein ratio directly impacts pricing and cost control. If a dish has too much protein, the cost becomes too high, which lowers its value-for-money appeal and makes it less viable as a mass-market option.

In terms of cuisine style, we prefer dishes that offer emotional value to consumers. For example, people are often more willing to pay for Western food because it’s uncommon in daily life and hard to prepare at home—some dishes can trigger an emotional response.

Additionally, the operational process needs to be simple and highly standardized, allowing the format to cover multiple meal periods and reduce dependence on labor. Focusing on these fundamentals allows for a restaurant model with a solid economic structure.

I’m still paying close attention to the tea beverage market. However, I want to emphasize that business model recombination is the larger trend. In recent years, we’ve seen frequent integrations of tea with coffee, baked goods, and other formats. This is a natural evolution in the market. When supply becomes abundant, individual unit output tends to decline. To improve per-unit output, diversifying product categories becomes a necessary strategy.

China Entrepreneur: In today’s stock-based market, what advice would you offer to companies trying to innovate?

Victor Zhang: First, strategize before taking action. Innovation should be traceable and purposeful, start by clearly understanding what you want to do. Then, engage with experts, entrepreneurs, and investors across various fields to gain deeper insights into consumers, categories, and the industry as a whole.

Second, get personally involved. For founders working on their second growth curve or building new business models, this isn’t a task you can delegate. You must actively participate in a way that suits your strengths and devote sufficient time, energy, and resources to the process.

Third, stay open-minded. When creating something new, it’s critical not to be constrained by past experience—especially if you’ve been successful before. That success can make you overly reliant on outdated models.