- Discount Resurgence in Retail, Revitalizing Retail with Freshness

- Introduction: Overview of Lopia's Business Model

- History: The Dream of "Meat for All Children"

- Demand: Lopia's Solutions to Consumer Pain Points

- Supply Chain: Choosing, Producing, and Selling Quality Meat

- Procurement and Operation: You're the Boss in This Category

- Dynamic Upgrading: The Deepening of Corporate Barriers

- Summary: Inspiration for Chinese Retail Enterprises

Discount Resurgence in Retail, Revitalizing Retail with Freshness

The premise of this article is to assist retail enterprises in their discounted transformation.

“Discounting” undoubtedly stands out as the hottest topic in the retail industry this year. The anxiety brought about by the current environmental changes can easily lead retail enterprises into the pitfalls of simply imitating successful overseas formats or excessively focusing on short-term price strategies. Yet the essence of “discounting” lies in the strategic choices and capacity building of enterprises.

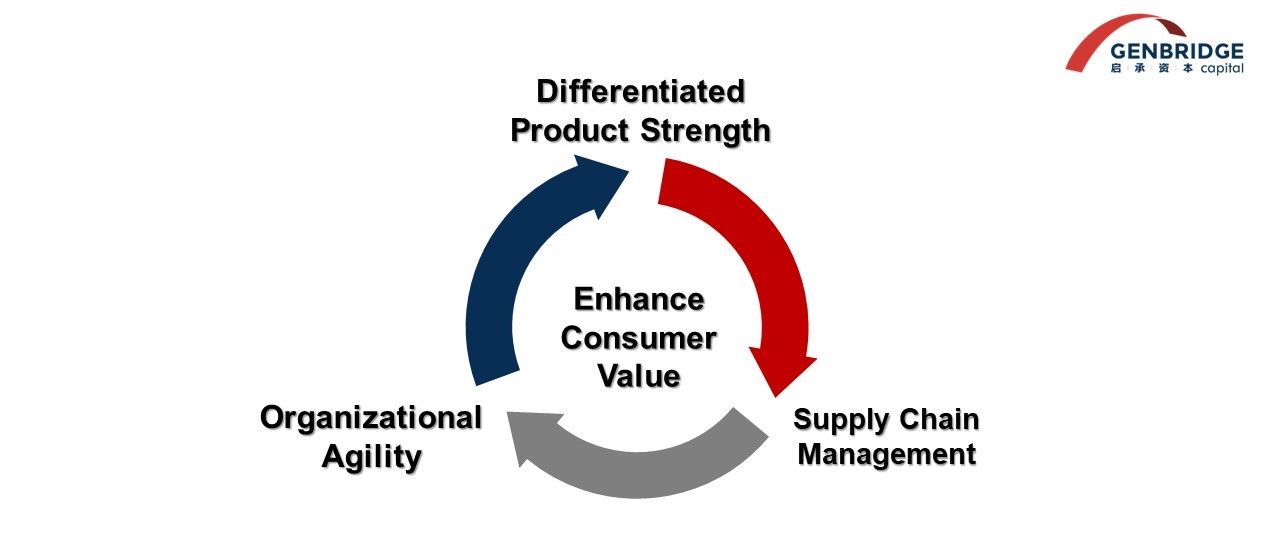

We believe that discounting in retail needs to emphasize the following three aspects:

- Differentiated Product Strength: Choose categories with advantages, address consumer pain points, and excel in product development, and pricing.

- Supply Chain Management: Based on the natural characteristics of categories, select corresponding vertical supply models, establish trust with upstream partners, and reduce the bullwhip effect.

- Organizational Agility: Improve organizational agility through incentive systems, allowing employees to proactively tackle complex issues, thereby enhancing operational efficiency.

Among these, differentiated product strength is often the most overlooked. China’s retail industry has a vast supplier system, with most companies selling products from an “open-source” supply chain. Traditional retail enterprises mainly focus on upstream bargaining, selection of products, corruption control, and the management and operation of stores. They collect shelf fees from suppliers/brands but do not put enough emphasis on how to cultivate their own dominant categories through deepening supply chain capabilities.

In the selection of retail categories in China, fresh products hold exceptionally high value. They have a broad and frequent demand spectrum, contributing to gaining consumer trust. However, due to the complex supply chain management and homogeneity of fresh products, there are few instances overseas where discount retail achieves both price and quality advantages with fresh products. How to achieve differentiated product strength through the fresh product category is a pressing issue for the Chinese retail industry.

This study will introduce a discount retail case focused on fresh products: Lopia, a Japanese food supermarket.

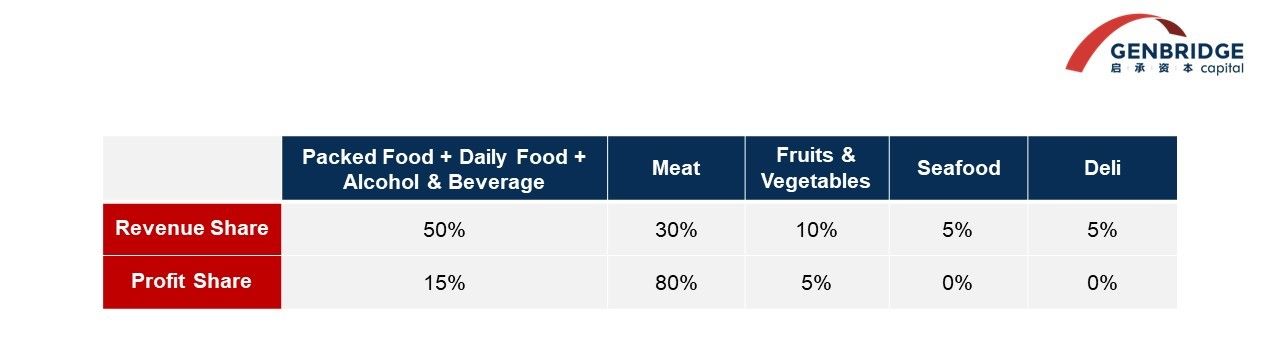

Lopia positions itself as the “Japanese version of Costco for four-person families” and is a manufacturing-oriented food retail channel with meat products at its core. The company has turned fresh products into profitable items, with 30% of revenue from meat contributing to 80% of profits. With the philosophy of “meat for all children,” the company deeply cultivates the supply chain capabilities of meat products and achieves competitive advantages through the integrated procurement and sales system in its stores.

As Lopia is not publicly listed, there is very little publicly available information. This study is the first comprehensive research in both China and Japan. We have reconstructed the competitive capabilities and development path of the company through store visits, expert interviews, and collation of second-hand information.

The article is divided into six sections:

- Introduction: Provides an overview of Lopia’s fundamentals and business model.

- History: Explores the founder’s philosophy and the significant changes the company has undergone.

- Demand: Examines consumer pain points and Lopia’s solutions.

- Supply Chain: Assesses the vertical supply capabilities that contribute to meat product strength.

- Procurement and Operations: Details the incentive-driven, integrated procurement and operational system.

- Dynamic Development: Understands the capacity building of discount retail from a dynamic perspective.

Introduction: Overview of Lopia's Business Model

Lopia’s full name is “食生活♥♥Lopia” (pronounced as “love, love”), meaning “Low Price Utopia enriching people’s dietary life.” Established in 2009, the brand is owned by OIC Corporation. Since its inception, Lopia has witnessed its revenues soaring from 27.7 billion Japanese Yen (approximately 1.8 billion RMB) in 2009 to 340.1 billion Japanese Yen (around 17 billion RMB) in the latest figures, boasting a CAGR of 21%. It stands out as one of the few Japanese retail enterprises with sustained high-speed growth and profitability.

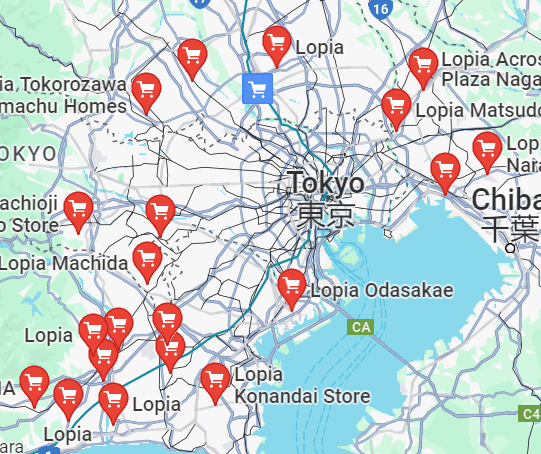

Lopia’s growth is anchored in maximizing sales performance at individual stores, with each new store quickly establishing its presence. Currently, Lopia operates 81 directly-managed stores, having opened 8 new stores in 2023 alone. The average annual sales per store hover around 230 million Chinese Yuan, with a total of 1,700 full-time employees, each contributing approximately 10 million RMB in sales revenue. Both store sales and personnel efficiency are double the industry average in Japan.

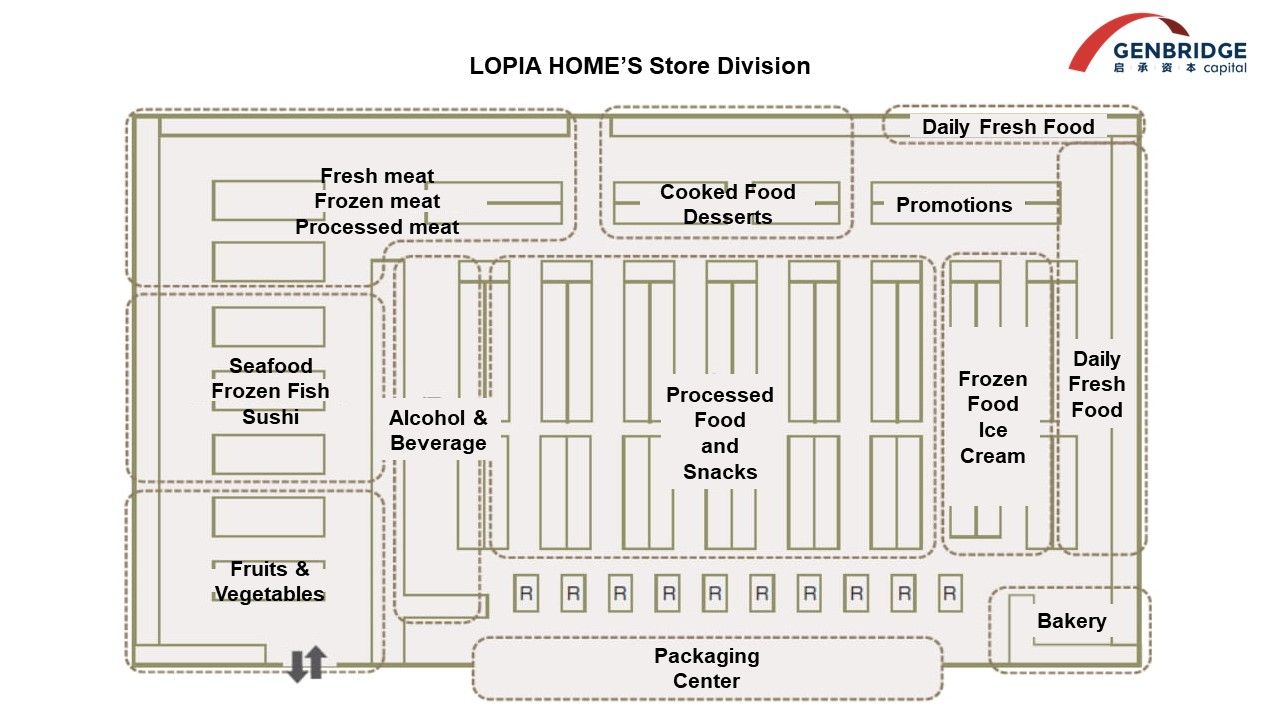

The store size ranges from 2,000 to 3,000 square meters, offering approximately 20,000 SKUs across categories such as vegetables, meat, seafood, daily necessities, packaged foods, and frozen foods. The channel has made clear choices in product selection, focusing on food and excluding non-food categories like household and personal care. To cater to the needs of four-person families, many food items are packaged in large sizes of around 1 kg.

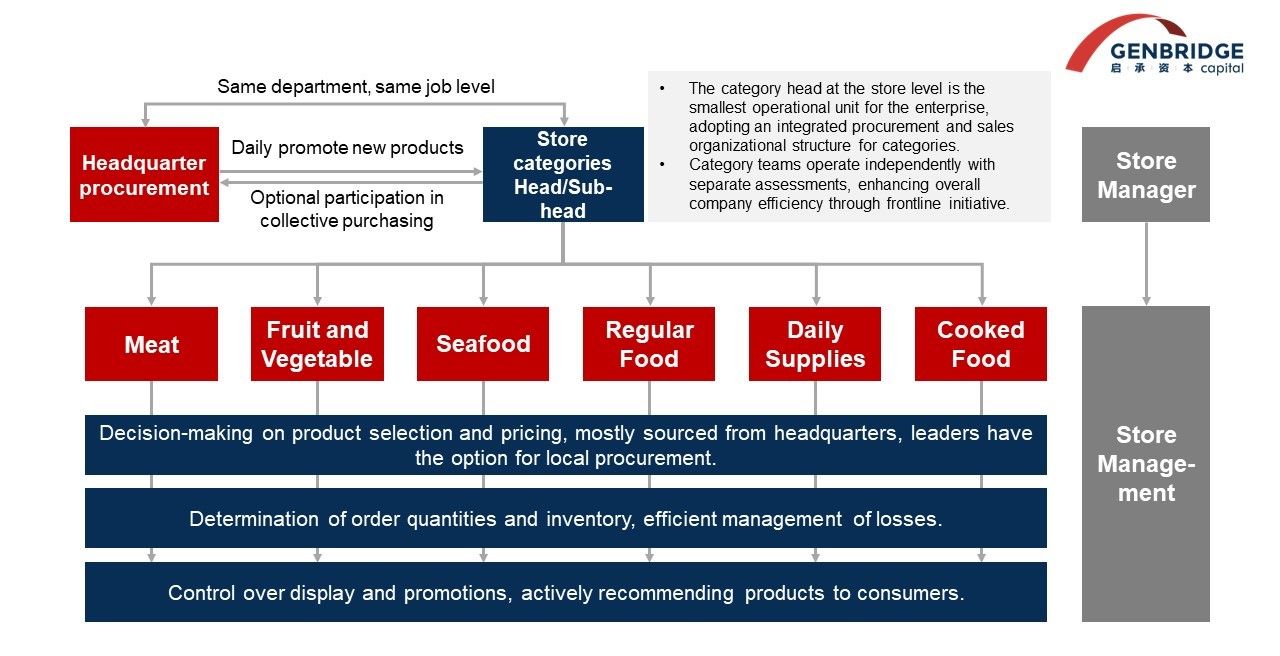

To address complex operational issues, Lopia harnesses the enthusiasm of frontline employees. The company employs an integrated procurement and sales system within each store category, with category managers acting as independent business units responsible for product selection, pricing, ordering, display, and some procurement, all accounted for independently.

Situated relatively far from the city’s core areas, Lopia’s stores are ideal for consumers looking for one-stop shopping. Each store covers a radius of 20 kilometers, with most consumers driving for over half an hour to make a weekly purchase. It’s noted that most consumers spend over 500 RMB per shopping trip. In the stores, it’s common to see a cart filled with three brimming baskets.

Lopia strategically selects locations in older properties, leveraging its strong ability to attract foot traffic to negotiate rents, keeping rental costs at a low 3%. The most famous Lalaport Tokyo Bay store, situated in a shopping center in Funabashi, Chiba Prefecture, established in 1981, introduced Lopia during a large-scale renovation in 2012. The store’s sales area is approximately 2,000 square meters, with annual sales reaching 600 million RMB.

Lopia’s unconventional category profit structure (shown below) is distinctive. 30% of revenue from meat contributes to 80% of profits. It can be inferred that the income from other non-profitable categories comes from the associated purchases when consumers buy meat. Lopia, through a strategy of thin profit margins and high volume, maximizes gross profit by leveraging the natural high customer value of meat and the high average transaction value of purpose-driven meat purchases.

Rather than being a discount supermarket operating multiple categories, Lopia can be seen as a killer store for meat categories that satisfy consumers’ collective purchasing needs. Meat is Lopia’s flagship category, with display area and SKU numbers three times that of other retail channels of similar size. Beef, ranging from low-end imported cuts to high-end domestic Wagyu, covers three main price ranges, each with dozens of different cuts and parts. Lopia’s meat profit margin is reported to exceed 40%. The company owns its chicken farm, meat processing plant, and meat product processing plant.

Lopia’s meat prices are 10% to 50% cheaper than its competitors. In the table below, we compare some meat prices between Lopia and the mid-range Japanese supermarket, Life.

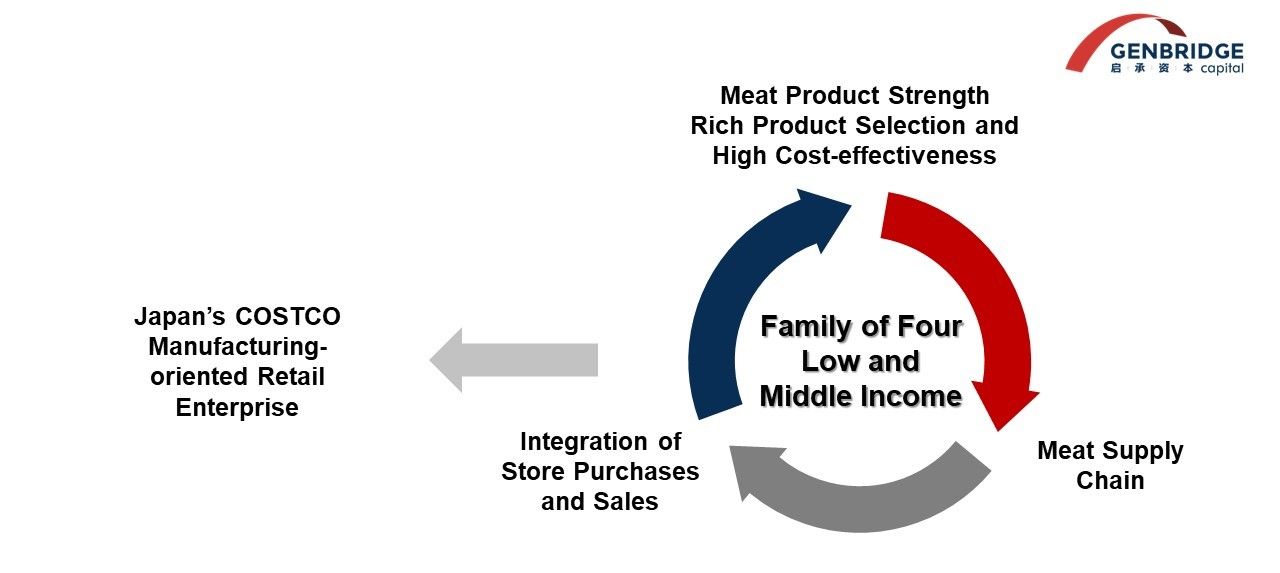

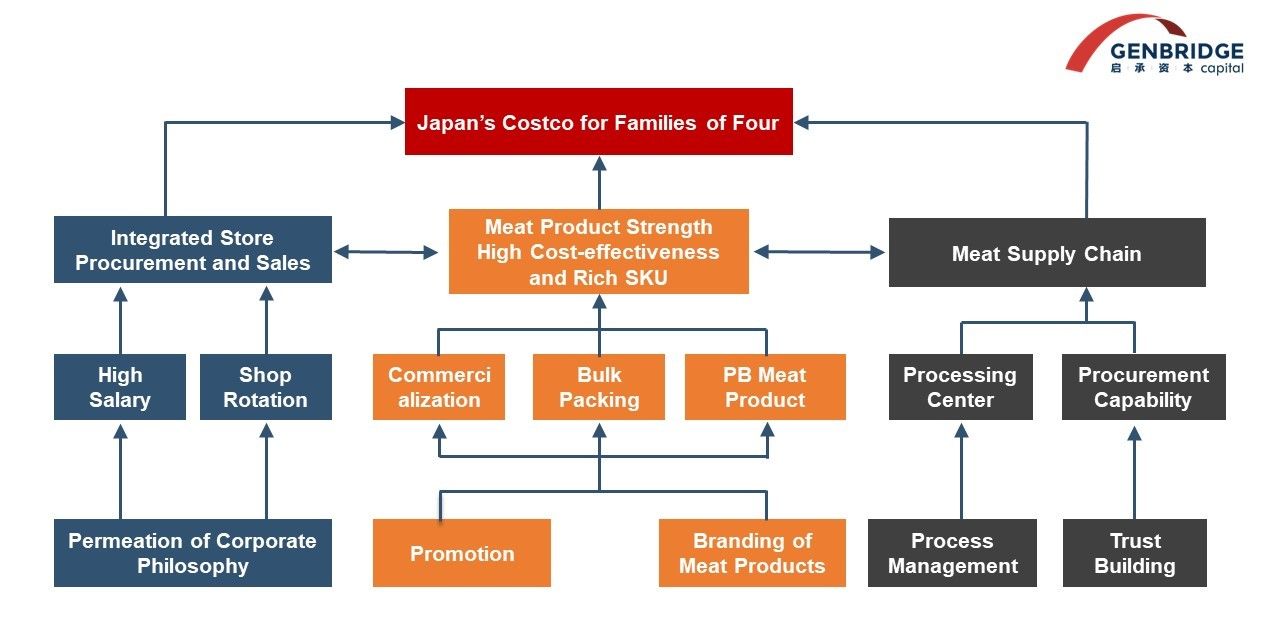

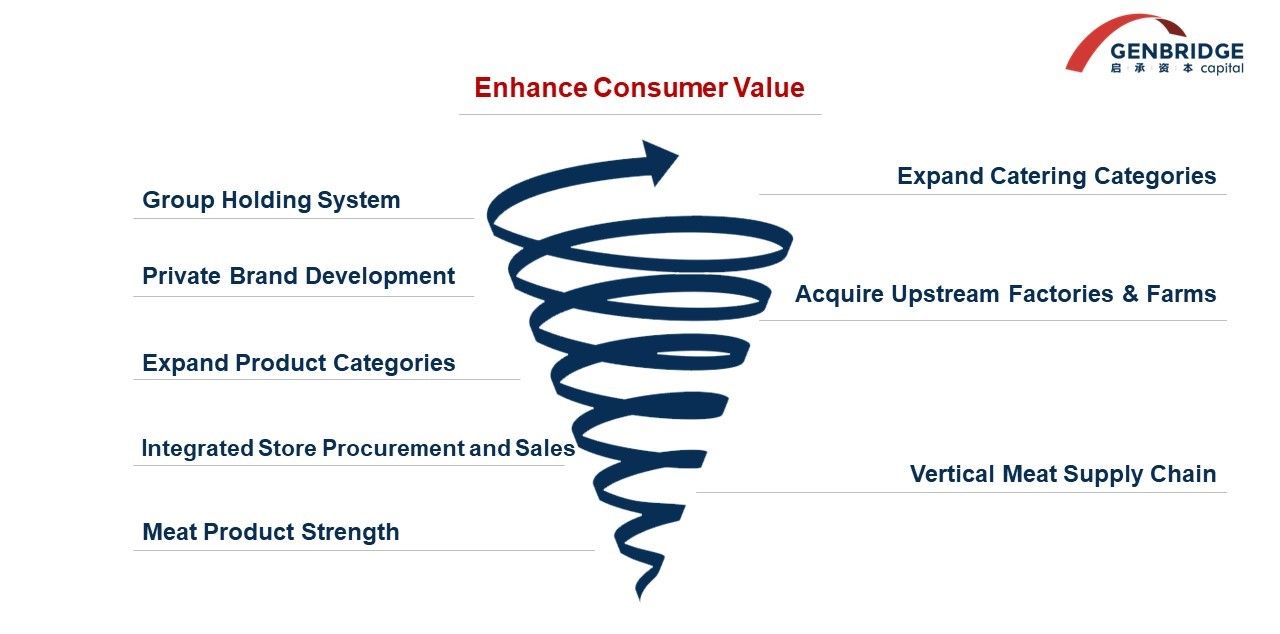

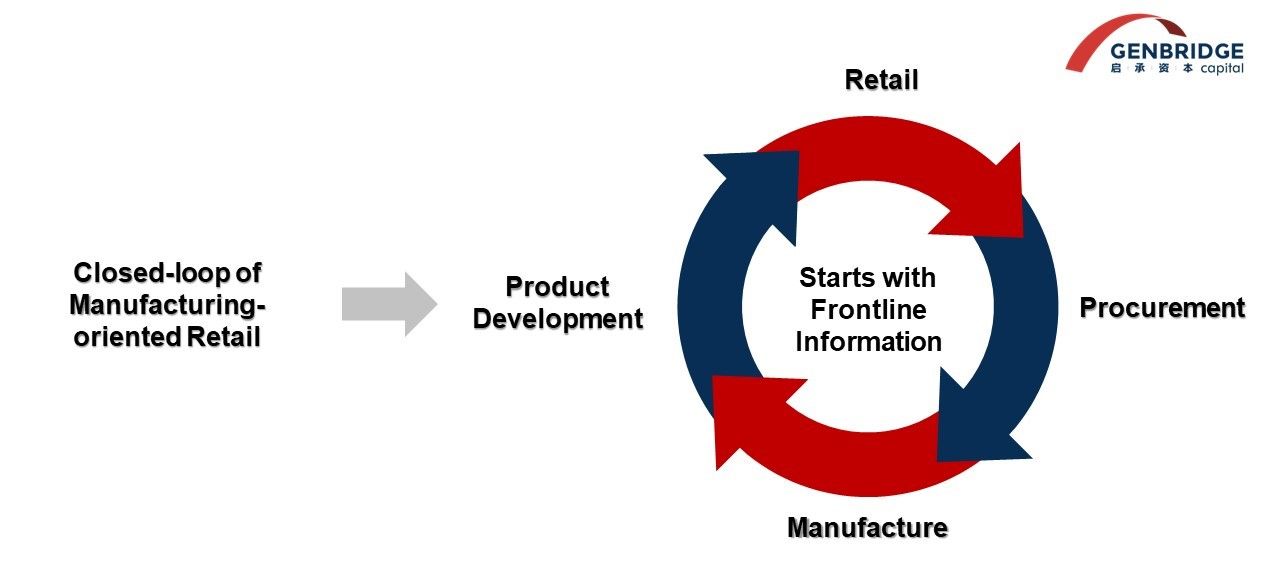

Lopia’s business model can be deconstructed into the following two diagrams. First, from a dynamic perspective, Lopia has found the ability combination that matches between product strength, supply chain, and organizational agility, continually strengthening its capabilities to serve its target audience. Second, from a cross-sectional perspective, it showcases the sub-skills behind each core competency supporting Lopia.

History: The Dream of "Meat for All Children"

Lopia’s precision in cultivating the strength of its meat products is inseparable from the founding principles of its visionary founder, Hideo Takagi.

The founder of Lopia, Hideo Takagi, embarked on his entrepreneurial journey with the intention of “ensuring all children can afford meat.” Growing up amidst the ruins of post-war Japan, where there was a scarcity of food and people are starved every day. At that time, sausages provided by the U.S. military became a rare delicacy. Hideo Takagi often shares with his team during company meetings, “Back then, I could have one sausage every day. I liked it so much and didn’t want to just devour it, so I would lick the sausage until it is tasteless, and then eat it.”

From this ideal to the eventual establishment of Lopia, Hideo Takagi made numerous experimental explorations. Lopia’s earliest predecessor was called “Niku no Takarabako” (translated as “Meat Treasure House”), a stall specializing in meat products established in 1971 in Fujisawa City. It involved various ways of cutting and selling purchased meat. Hideo Takagi delved personally into product development, for example, flying to Germany to see the sausage production process and establishing a backend production center. This allowed stores not only to sell meat but also freshly made sausages and prepared foods, enhancing profit margins.

However, even the best quality products cannot escape the iteration of the retail channel. By the 1980s, Japanese consumers’ food purchasing channels had transitioned from community stores to supermarkets. Supermarkets possessed shallow processing capabilities and placed more emphasis on a merchandise combination marketing strategy centered around 52MD. The popularity of the supermarket format transformed consumer purchasing from buying single items like a radish or a piece of meat to selecting solutions for three meals (meal solution). Faced with channel changes, Hideo Takagi had to transform. After testing the waters in 1980 and fully transitioning in 1996, it became “Yutakaraya” (translated as “Abundant Treasure House”).

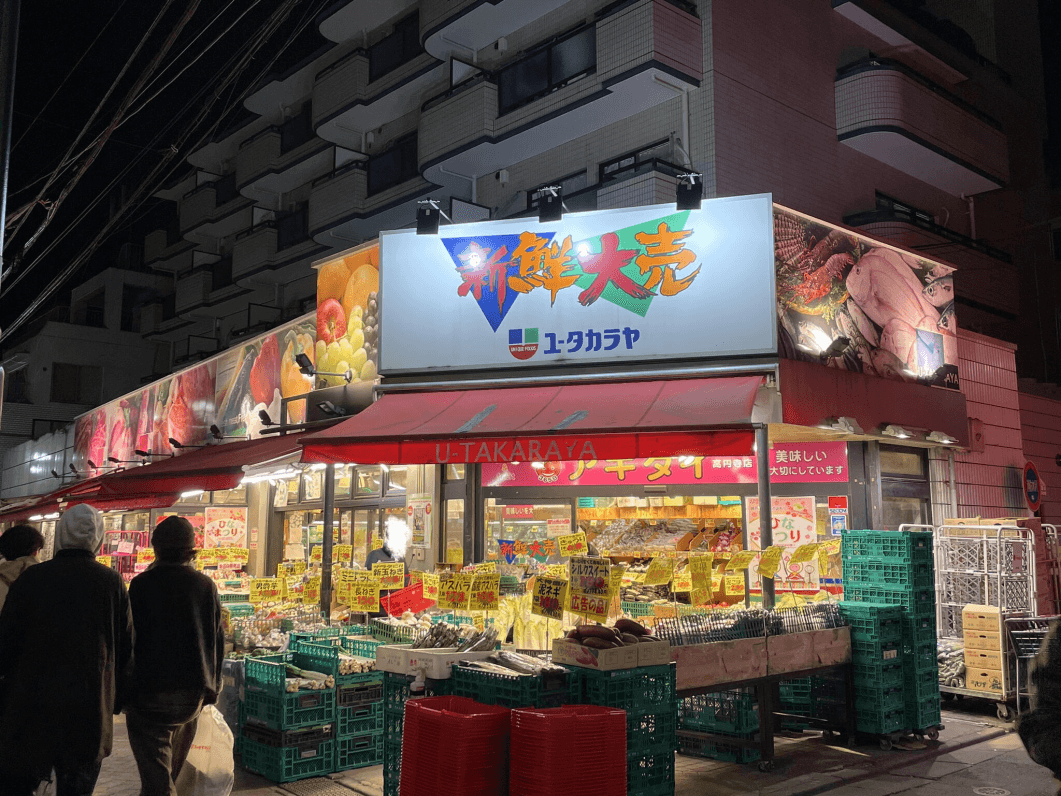

Yutakaraya Koenji store

Yutakaraya Koenji store

“Yutakaraya” was a medium-sized supermarket format with a core focus on meat, covering an area of approximately 700 to 1000 square meters. Initially, the company lacked category management capabilities other than meat, so vegetables, fish, and prepared foods were sold by inviting individual businesses from other categories. After learning the knowledge of various categories, Yutakaraya gradually shifted ordinary food, vegetables, prepared foods, and seafood to direct management. In 2007, Yutakaraya had about 21 stores with 18 billion Japanese Yen in sales revenue.

The true transformation from “Yutakaraya” to “Lopia” took place in 2011. After testing the Lopia format in 2009, the first store achieved significant success. High cost-effectiveness and a diverse range of meats earned the trust and wallets of consumers. At this point, Hideo Takagi, already advanced in age, wanted to hand over the business to his son, Yosuke Takagi. The company was renamed “Lopia” and redefined its mission: “Same things at cheaper prices, and better quality for the same price.”

What supports Lopia through each transformation? We believe it is still the commitment to “meat for all children.” Of course, this heartwarming story may well be a carefully crafted narrative by the company. Whether it’s true or not is not crucial. What matters is understanding how Lopia precisely caters to the demands of its target audience.

Demand: Lopia's Solutions to Consumer Pain Points

Lopia’s target audience is families with a yearly income of 4 million Japanese Yen, precisely the median income level for Japanese households. Approximately 5 million households in Japan fall into this income bracket.

Their need is to provide their children with as much beef as their salary would allow. Imagine a scenario where the father is working, but wages are stagnant; the mother is a full-time homemaker or has a side job, and expenses are on the rise. Younger siblings are left with hand-me-down clothes from older siblings. For children in families with this income level, protein intake mainly comes from chicken or pork, with little opportunity to afford the more expensive beef. However, every family wishes to ensure their children have a more nutritious diet, making Lopia, with beef as its main category, more likely to gain the trust of consumers.

Queue before the opening of the Lopia Lalaport Tokyo Bay store

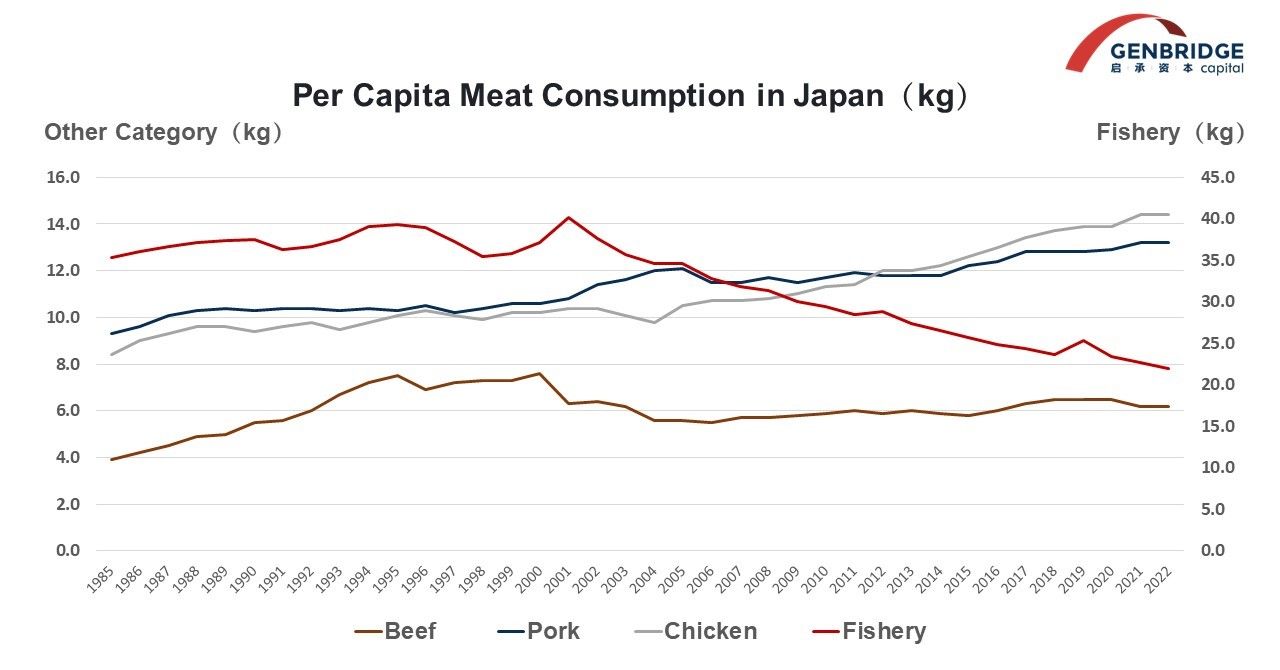

From a macro long-term perspective, meat consumption reflects changes in the demand structure of Japanese society: the desire for beef but the inability to afford it, the cost-effectiveness of chicken and pork, and the reluctance to purchase seafood due to its perceived difficulty in preparation. In the 1980s to 1990s, a period of economic prosperity, per capita beef consumption in Japan increased from 4 kg per person per year to nearly 8 kg, only to fall back to around 6 kg after 2000. Even during economic downturns, middle and lower-class Japanese consumers wanted to retain the habit of consuming beef. After 2000, demand for pork and chicken continued to rise, but seafood consumption experienced a cliff-like decline. Seafood requires a higher level of culinary skills, and pre-cut pork and chicken are easier to cook.

Lopia’s core focus on the needs of family consumers is also reflected in its operational details. Contrasting the display of yogurt shelves, a discount channel with standardized operations would place the best-selling plain yogurt on the first layer of the refrigerated cabinet, where fits the most items, for greater efficiency. However, Lopia places fruit-flavored yogurt, which may not have the fastest turnover, on the first layer. This way, children can easily see the fruit-flavored yogurt they like, linger in front of the yogurt shelf, and ultimately increase the probability of the family purchasing other yogurts.

Mini train in the store

Lopia’s retail space design also incorporates ingenious elements. In the snack area of the store, a small train whistle sound imported from overseas is heard echoing above. The small train attracts children, prompting them to explore the snack area while their mothers shop. This prevents children from tugging at their mother’s sleeve and saying, “Mom, let’s go home,” reducing the opportunity cost and allowing mothers to purchase more needed items.

Supply Chain: Choosing, Producing, and Selling Quality Meat

How does Lopia meet consumers’ latent demand for meat?

The answer lies in three key aspects: choosing, producing, and selling.

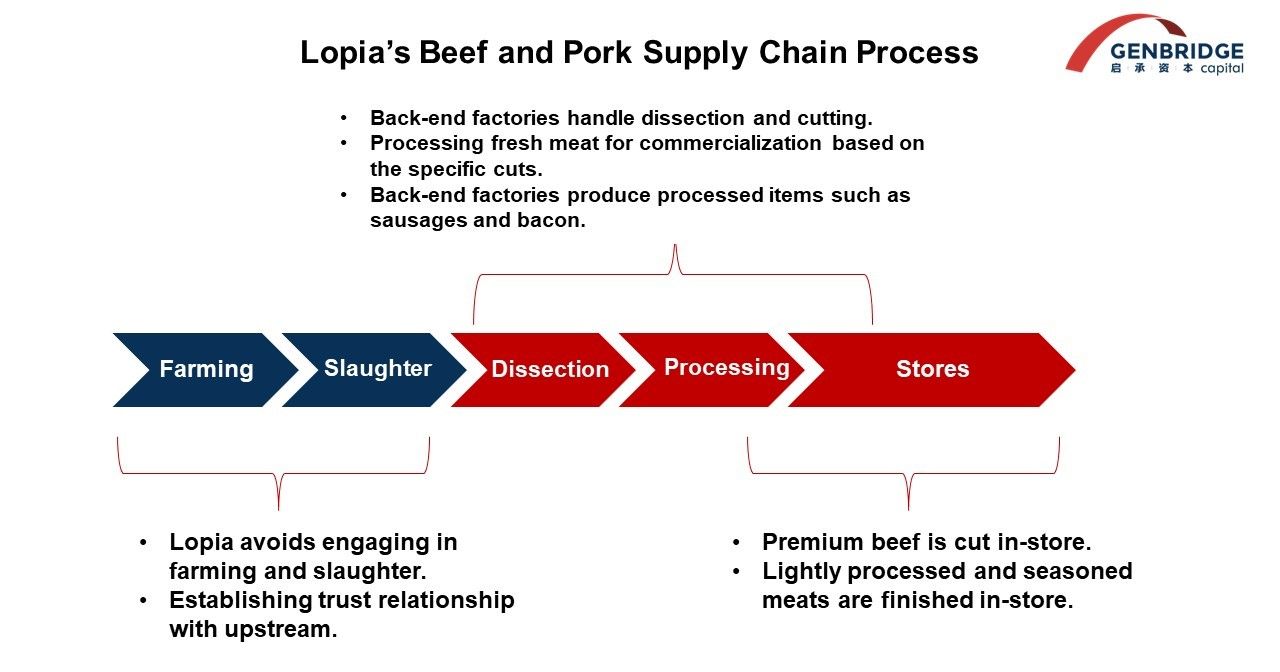

Choosing: This refers to the method and quality of procurement. Unlike regular supermarkets in Japan that simplify operations by purchasing different cuts of beef and pork, and then conducting cutting and selling at the backend factory or store, Lopia engages in multi-part/whole-head procurement. This method requires assessing the yield after cutting during procurement. Rooted in its origins as a meat store, Lopia has accumulated rich experience and channels in meat procurement.

“Choosing” also means establishing stable trust-based relationships with upstream suppliers. Founder Hidetake Takagi still visits the meat wholesale market every morning to personally procure raw materials. This proactive approach is a form of respect for upstream wholesalers and farmers. For livestock farmers, if the prices offered by various buyers are similar, they prefer to sell their hard-raised livestock to companies that treat them well and can market the products effectively. According to a meat expert, suppliers at the Yokohama meat wholesale market are willing to provide Lopia with a few extra points of margin. Additionally, Lopia primarily relies on cash purchases, and most stores do not accept credit card payments.

Producing: This involves channel-based commercial development of meat products. Lopia has extensive experience in the commercial processing of various meat cuts, maximizing the sale of high-value cuts with higher profit margins. Furthermore, Lopia processes meat into different forms, allowing consumers to choose pre-cut products based on recipe requirements. Through different cutting methods, different cuts, and different price ranges, Lopia achieves a diverse range of meat products.

Lopia noted the flavor difference of different parts

On this basis, Lopia blends the profit of various cuts of meat from a whole head/animal. The cost of purchasing in multi-part/whole-head method is about 15% lower than purchasing individual cuts. However, this method also tests the channel’s ability to utilize various cuts of meat; purchasing without efficient utilization increases costs. Lopia effectively uses the scraps generated during cutting and production in the backend factory. While other channels may discard these scraps, Lopia utilizes them to create products such as sausages, ham, hamburger meat, and more.

Lopia’s Private Brand meat products are more than 30% cheaper than National Brand standard goods and reach the same taste level. These PB products, including sausages, contribute to the source of Lopia’s meat profits. Lopia’s self-owned sausage products have a full-chain gross margin of over 50%, and some marinated seasoned meat products can achieve a gross profit margin of up to 80%. These products are prominently displayed in Lopia stores, using a large quantity of individual items.

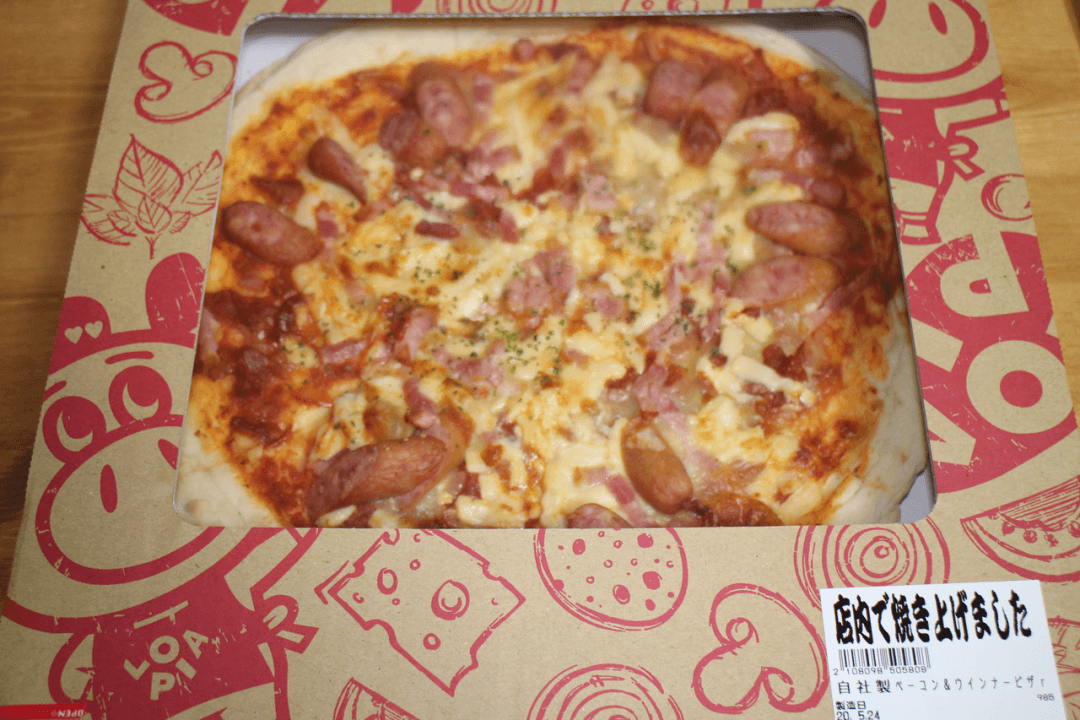

To further enhance the added value brought by self-processing meat products, Lopia has also introduced distinctive ready-to-eat products. Lopia’s ready-to-eat products do not include seafood, vegetables, or other categories outside of meat products. All ready-to-eat products revolve around maximizing the value of meat products. For example, Lopia’s freshly baked sausage and bacon pizza (27 RMB) cleverly utilizes the value of freshly baked pizza and the meat product image of the Lopia brand, becoming a star product in the ready-to-eat category. With the profit support from these product categories, Lopia can offer beef products with the strongest consumer value at lower prices.

Freshly baked sausage and bacon pizza at Lopia

Achieving exceptionally high profits through meat products signifies the transformation of the backend meat processing factory from a cost center to a profit center. The traditional meat processing factories of chain channels typically function as a “sorting center,” primarily focusing on portion control. For instance, after the slaughter of pigs, when transported to the factory, the backend factory decides which parts to use for fresh cuts, which to freeze, and which to wholesale to catering channels, managing comprehensive cost and loss control. However, Lopia amplifies the product development function of its backend factory, utilizing different cuts through processing techniques and commercialization thinking to maximize profit.

Lopia has also organized its meat processing facilities based on different product price bands. The backend factory mainly handles the processing and commercialization of mid- to low-end meat, achieving maximum efficiency with the lowest labor cost. The factory has imported production experience from the world’s largest electric motor company, minimizing costs throughout the entire process. Store processing mainly focuses on cutting high-priced domestically produced premium beef, effectively controlling losses while providing consumers with a stronger sense of value.

Lopia’s meat processing factory

The inherent characteristics of meat products contribute significantly to Lopia’s strong image of cost-effectiveness and high quality. However, achieving good quality is not solely a matter of waiting; it requires effective strategies to promote and sell the products. This involves strategies such as establishing price perceptions, store marketing activities, and promoting brand value.

Lopia establishes a perception of high cost-effectiveness through the anchoring of prices with slices of premium beef. While the gross margin for this category is only about 15%, the selling price is less than half of that in department stores and 30% cheaper than other food supermarkets. The price of premium beef at Lopia ranges from 20 to 25 RMB per 100g, allowing consumers to buy a slice of beef with snow-like meat quality for only around 50 RMB. Because premium beef is not a daily purchase for Lopia’s target consumers, they may not fully understand the price, creating an impression of “affordability.”

Grade 4 “Source Beef” Thick-Cut Slices 130rmb/539g; Kumamoto-Produced Beef Steak Meat, Frost Drop Shoulder Core Muscle Meat 110rmb/440g

The variance between the expected quality and price of Lopia’s beef comes from the branding of Lopia’s beef. The premium Wagyu product line from Lopia is named “Gen Beef” and has its own set of grading criteria. However, “Gen Beef” does not have strict environmental requirements for breeding like “Kobe Beef” or “Matsusaka Beef”; it is a general term used by Lopia for domestically produced high-end black-haired beef. This branding approach leads consumers to believe that “Gen Beef” is close in quality to “Kobe Beef” and “Matsusaka Beef.” In reality, the taste of “Gen Beef” is not on par with true branded beef, but this is not crucial for Lopia’s consumers.

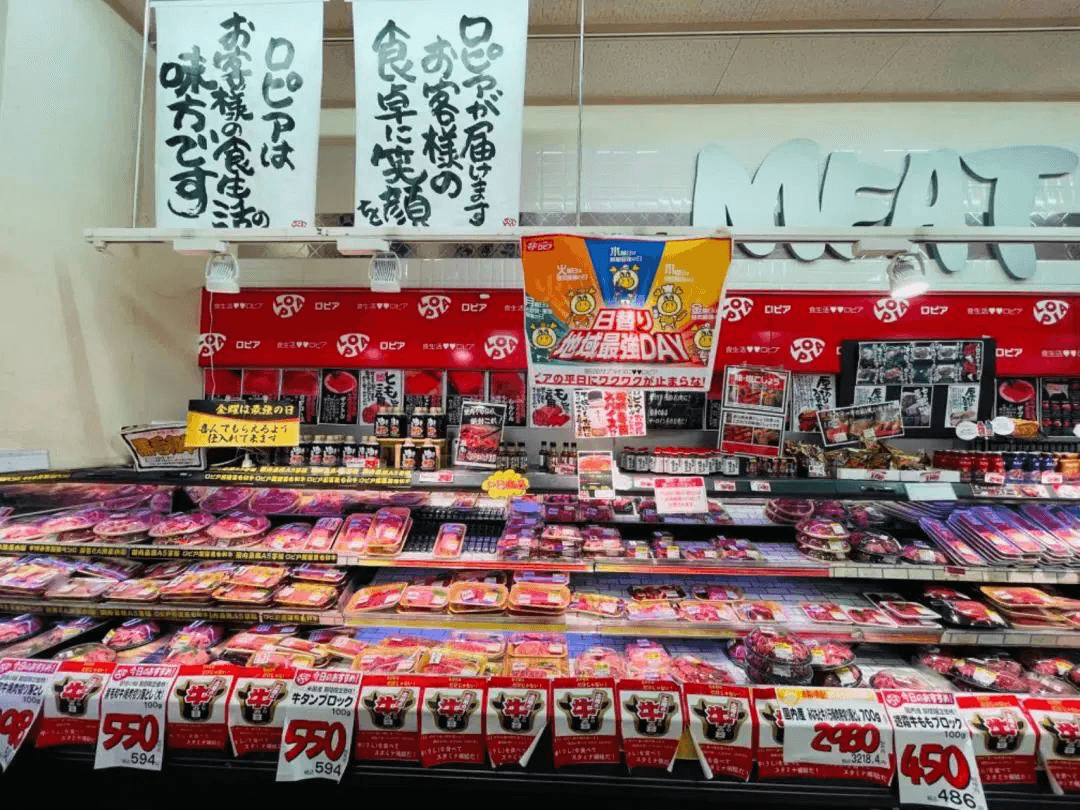

In terms of sales, Lopia actively employs flexible promotional activities, leveraging the channel’s perception of low-cost, high-quality meat to attract consumers. For example, Lopia holds a “Meat Day” promotion on the 29th of each month (29 is a homophone for “meat” in Japanese), which has become a day many families visit Lopia. Additionally, Lopia has “Local Strongest Day” promotions every day other than weekends, offering specific items at the lowest regional prices. About 3% to 6% of the product SKU quantity is on rolling promotions.

Regional Strongest Day Poster; Lopia Meat Day Poster; Lopia’s Meat Product Promotion

Procurement and Operation: You're the Boss in This Category

The challenges of running a manufacturing-based retail business lie in the need to develop products, manage factories and suppliers effectively, and oversee store operations. This often results in business resources exceeding the company’s management capacity, leading to various managerial issues. Therefore, fully unleashing the enthusiasm of front-line employees to solve complex problems is an essential prerequisite for successful manufacturing-based retail.

Lopia has adopted a unique integrated procurement and sales model, mobilizing the enthusiasm of front-line employees to manage the high complexity of fresh products upstream and real-time store management. This model can be understood as the company creating a platform for employees, allowing each category manager in the store to manage their category like operating a booth in a market. This is evident in Lopia’s store layout, where each category not only represents a store area but also has a separate store name. Categories such as meat, vegetables, seafood, and prepared foods all have their own store names.

The integrated procurement and sales model emerged in Japan after 2000, and companies with similar models to Lopia include discount store Don Quijote and fresh supermarket Ozeki. According to an expert, employees from Don Quijote and Ozeki who switch to Lopia can quickly assimilate into the company culture and excel in store purchasing and operational tasks. In comparison, employees from companies adapted to centralized management by headquarters, like Aeon and Ito Yokado, find it challenging to adapt to Lopia’s management style.

Under this model, store category managers are responsible for their performance and need to bear the profit and loss of their categories. Typically, Lopia’s stores have six major sections, each with a main and assistant category manager responsible for product selection, purchase volume, pricing, and a portion of procurement. Relying solely on centrally procured goods cannot achieve differentiation, so many category managers go to wholesale markets in the morning to purchase directly. The ratio of store purchasing to headquarters purchasing varies between stores, with experienced category managers personally procuring 30% to 50% of the goods. These employees act like individual operators, finding ways to sell the products they purchase every day.

Store category managers and headquarters category purchasers belong to the same department, and both hold equivalent job positions. Most of the headquarters purchasers have experience as store category managers on the front line. They send new products to stores every day, and stores can choose to accept them. The headquarters category purchasers are responsible for the profit and loss of the entire category. In contrast, store managers at Lopia have the least authority, primarily managing store checkout, cleanliness, and the management of non-formal staff.

To avoid friction between headquarters and store purchases, Lopia places a strong emphasis on the company’s overall understanding and freshness of frontline stores. Even high-ranking executives serving as executive directors at headquarters may be sent to stores as store managers in the following year to refresh their perspectives. Moreover, to combat corruption issues in procurement, headquarters exercises strict control over store category managers, prohibiting them from having meals with any wholesalers. Infidelity, theft, violence, and bribery are the four cardinal sins Lopia most detests, and if discovered, individuals are required to leave the company.

Supporting the integrated procurement and sales of stores is Lopia’s salary structure. The average age of Lopia employees is around 30, much lower than the average age of 40 in Japanese retail companies. Young employees not only have more physical energy but also a stronger desire for income growth. Lopia’s salary level is about 20% higher on average, with corresponding performance incentive mechanisms. This approach provides significant motivation for young employees who join Lopia immediately after high school graduation. They not only receive the same salary as new employees with a university degree but also quickly rise to higher positions. In other words, Lopia achieves a model where three people do the work of five, taking home the salary of four through high salaries and strong incentives.

An employee who became the meat category manager at the age of 23 (from Lopia’s official Facebook)

Lopia’s ability to manage store procurement is also due to the high penetration of corporate culture. One employee told us, “The penetration of the company’s philosophy and vision is very high, to put it bluntly, employees are brainwashed.” All employees have a strong sense of direction toward the company’s growth direction and goals. At Lopia, there is no standardized corporate management manual, highly depending on individual capabilities. The organizational management of the company is also very flat, with director-level positions responsible for managing categories having no other positions below them. Everyone is essentially equal, focusing on creating value.

The integrated store procurement system brings competitive advantages to each store within its commercial area. The competitiveness of stores comes from the coexistence of operational unity and flexibility in enterprise operations. The fresh retail channel requires actively adjusting the product structure, and constantly providing consumers with promotional prices, seasonal products, and experiential value to increase the frequency of consumer purchases. However, on the other hand, companies also need to collaborate across departments, implement promotional plans, and gain price advantages through the reverse procurement of scaled quantities through store sales. Balancing unity and flexibility, Lopia’s category managers can independently traverse multiple departments within traditional enterprises, effectively utilizing the effects of centralized procurement by headquarters and uniformly implementing promotional activities. At the same time, they can flexibly seize procurement opportunities, select competitive products, and give consumers more reasons to visit the store.

For emerging retail enterprises to succeed in a saturated market, they must have strong individual store competitiveness. The CEO of Don Quijote once told us that in a saturated market, it is a battle between stores, and only by winning every close combat can one achieve a victory at the campaign level. To ensure that each store has sufficient combat power in its commercial area, stores must maximize individual initiative in product selection, pricing, and promotional activities with appropriate support from headquarters. Lopia’s integrated store procurement model achieves this mechanism in the fresh food sector.

Dynamic Upgrading: The Deepening of Corporate Barriers

The development of a business is not linear but rather a continuous evolution in a spiral ascension. The main thread has always been the company’s continuous deepening of its advantages to solidify them into competitive barriers. Let’s further understand Lopia’s development choices from the perspective of dynamic upgrading.

In 2023, Lopia implemented a structural adjustment by establishing the OIC Holding Group, further decentralizing managerial authority, and assigning various subsidiaries to professional managers. The founder and top executives then focused their time and energy on high-quality decision-making, better managing the expanding business radius.

The reason behind the significant adjustments made by OIC Group was Lopia’s integration of the supply chain in 2014, involving mergers and the establishment of multiple enterprises. This necessitated a new management system to cope with the increasing complexity of tasks. Some of the companies acquired by Lopia include “Kai Shokusan” in the chicken supply chain, the seasoning production factory “Marukoshi,” the agricultural wholesale market “Saiwai ichiba,” and the soy sauce factory “Toragawa Soy Sauce.” These entities became crucial components in deepening Lopia’s product strength and supply chain, consolidating the advantages established in the meat category.

To encourage cross-category purchases between meat products and other goods, Lopia further replaced commodity products with PB items to improve profit margins beyond the fresh food category. Currently, PB products under the Lopia brand account for less than 10% of non-fresh category sales, with a future goal of increasing it to 30%.

The development standard for Lopia’s PB products adheres to the principles of being delicious and reasonably priced, without compromising quality for lower costs. PB development follows an internal bidding system, allowing employees to define products, find suppliers, and submit proposals to the headquarters. Every month, a high-level executive meeting at the headquarters decides whether a new product is good enough for sales, with “taste quality” as the core criterion. In 2022, OIC acquired the well-known Japanese culinary expert, Rokuro Dojo, and his studio, enhancing Lopia’s capability to plan high-quality PB products. The development principle for PB items is not to create products that lack differentiation.

Lopia’s development started with a breakthrough in meat products, progressing to a vertically integrated meat supply chain, transitioning to a unified procurement and sales operation model, and returning to the enhancement of PB product strength and deeper supply chain cultivation. Lopia aims to achieve a revenue target of ¥2 trillion (100 billion RMB) by 2031. As the company scales up and managerial challenges increase, its business model continues to upgrade and evolve. OIC Group is also expanding its business into the incubation of restaurant brands, continuously pushing the boundaries of the company’s management and capabilities.

Summary: Inspiration for Chinese Retail Enterprises

Lopia’s experience is indeed worth learning from, but entrepreneurs should refrain from impulsively saying, “Let’s just follow suit.” In the past, many Japanese retail companies tried to emulate the United States, but none of them succeeded.

In the retail race, we are all students, and the real teacher is always the consumer. We need to observe who is buying what kind of products and whether their needs are being met within the channels.

The defining characteristic of “manufacturing-oriented retail,” as identified by Lopia, is starting from consumer and frontline employee feedback, thereby driving the entire chain from product development, manufacturing, and procurement, to retail sales in reverse. All of Lopia’s improvements in business capabilities stem from understanding and digging deeper into consumer needs.

For readers and friends working in the retail industry, have you thought about which product category should be the flagship for your channel? Have you considered potential collaboration with supply chain enterprises? In what ways will you communicate and cooperate with them? Have you thought about how to motivate your frontline team?

The path to retail discounting poses many challenges. In 2024, GenBridge Capital is willing to advance together with all of you and learn collaboratively. Entrepreneurs are welcome to engage in discussions with us on how to navigate this journey.

Author: Tojiro Kataya, Senior Researcher of GenBridge Capital